Overexcitabilities: Drivers of Developmental Potential

Chris Wells & Frank Falk at the 2018 Dabrowski Congress

I’ll be celebrating my 51st birthday this weekend, and I’ve taken this week off from meetings. Last year, I was feeling some uneasiness about turning 50, so I gave myself the week off. I decided to do it again this year because unscheduled time for myself is exactly what I need as someone who never stops working or thinking about my work.

If you haven’t already, may you find a subject that engages you with the passion and sustained enthusiasm I’ve felt for studying the theory of positive disintegration.

I realized while working on this post that it was ten years ago tomorrow, on March 29, 2014, that I first downloaded a chapter by Dr. Michael M. Piechowski and discovered Dąbrowski’s theory.1 What a life-changing moment that was for me.

This has been a heavy month because my mother’s younger sister is dying. She may have passed by the time this post goes live. Facing the end of my aunt’s life has brought me renewed feelings of grief while recalling the loss of my friend and mentor, Dr. Frank Falk, last April. Those feelings led me to the audio file I’m sharing with you today.

2018 Dabrowski Congress

We’ve been talking about the upcoming Dąbrowski Congress this summer, and I hope this post will give you a taste of past Congress sessions.

I started working with Frank at the Institute for the Study of Advanced Development (aka Gifted Development Center) in November 2017. During that month, Frank asked me to present to him at the 2018 Dąbrowski Congress. It was the first time someone had asked me to team up with them for a conference presentation, and I felt very honored.

What would we discuss? At the time, I was interested in sharing what I’d learned in the literature review for NAGC 2017 about the evolution of overexcitability and developmental potential in the theory of positive disintegration. In our proposal, we said we would:

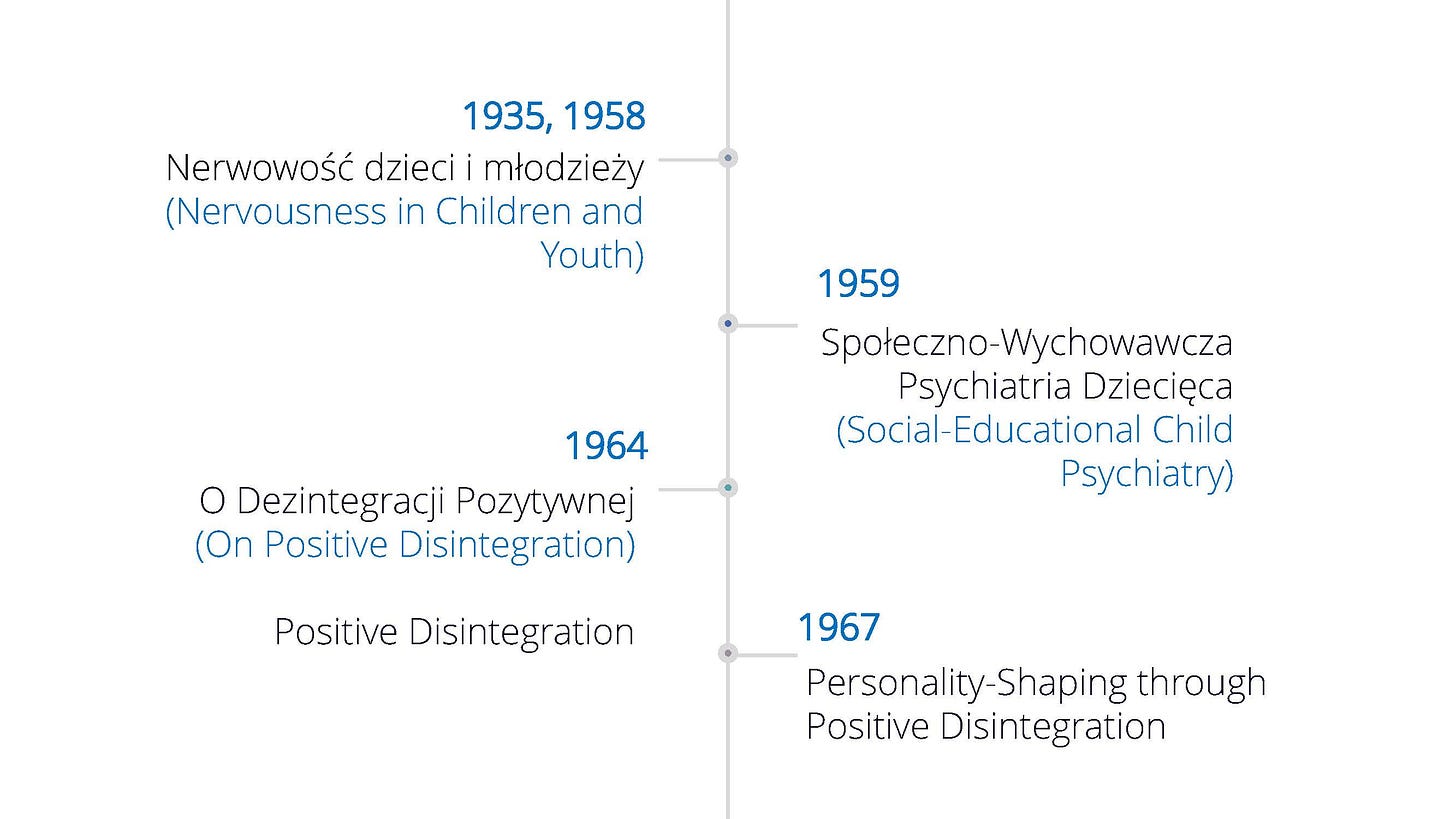

Describe the historical evolution of Dąbrowski’s overexcitabilities (OEs) by tracing the various uses of this term in Dąbrowski’s work from 1937 through 1996 with a timeline.

Provide a thesaurus of the original Polish terminology for OE and its English translations.

Demonstrate how the dynamisms arise from the OEs using case examples from Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions.

When we submitted the proposal, I was still a doctoral student. I defended my dissertation on June 29, 2018, two weeks before the Congress began in July.

It seems worth noting that the voice issue I described in Episode 52 was happening during the time I’m describing here. I was struggling to find my voice and didn’t know what I would do with the theory or my PhD.

Between submitting our proposal in early December 2017 and delivering our presentation at the 2018 Congress, Frank and I worked together to study how the terms overexcitability and developmental potential were used by Dąbrowski.

It’s my pleasure to share the edited recording, and I hope you will at least listen to the first ten minutes, which were all Frank. I’m also sharing an edited transcript with the slides we described in the session.

Frank mentioned a handout, and I’ve dug it up from my archive to share with you today. Click the download button below. It includes the references.

What can I say about what it was like to do this session with Frank and share my expertise about the theory with such a distinguished audience? It was an incredible experience. I consider it my true introduction to the Dąbrowski community, and it was so successful that it completely dysregulated my nervous system in a way I didn’t know how to deal with in 2018. I returned home from Illinois and couldn’t stop crying. I’ll save that part of the story for another time.

The keynotes in 2018 were delivered by Dr. Michael M. Piechowski (Episode 48)2 and Elizabeth Mika (Episode 17).

You can’t tell this by listening to the recording, but I was sometimes looking to Michael for confirmation, especially during my poor Polish pronunciation, which I’d like to apologize for in advance. I know we have some Polish subscribers, and I beg your forgiveness. Thanks to Michael, my pronunciation has improved since 2018.

I know some of you who are reading this post were at our session in 2018. Thank you for being here in 2024 and still supporting this work. You have my deepest appreciation.

Overexcitabilities: Drivers of Developmental Potential

By Chris Wells, PhD and R. Frank Falk, PhD

Presented on July 14, 2018, in Naperville, Illinois, at the 13th International Dąbrowski Congress.3

Frank: Well, good morning. My name is Frank Falk. And my job here today is to really introduce Chris Wells. Chris just completed her dissertation two weeks ago. [Applause]

She did a dissertation on parenting stress in parents who have 2E kids. And twice-exceptional kids, in this case, means kids that have physical disabilities, serious ones, as well as the sort of typical ADHD kind of stuff. So, that's kind of important.

Chris is the expert around here in qualitative analysis, and she's actually the director of qualitative research at the Institute for the Study of Advanced Development, where we both hang our hats.

What I really want to say though is that it's been a really great opportunity for me to get to work with Chris. I've been studying this theory since 1980. The last six months, I've learned more about this theory than I ever knew before because of working with her. So, it's been a real pleasure.

What she brings to bear is not only a huge interest in the theory, but skills. And one of the skills that she has is working with computers. She works with a particular program called QDA Miner. The QDA stands for Qualitative Data Analysis. What's nice about this program is that we can put in a search, and then it will pull out the paragraph that includes that search. So, if you're looking for a word like we were, “excitability,” then what happens is that it pulls out every example of that and gives you the paragraph, so it gives you the context. In addition to that, it gives you the reference, so it's all there at one time.

Now, that's really nice, and what she also did was to collect all of the works by Dąbrowski that are in English and put them into the computer. So, what we're talking about here today is an analysis of every time Dąbrowski used any word that had excitability in it, going from 1939 to 1996.

What did that do for me? It meant that I got to read through all of those paragraphs. And that's what I mean when I talk about really beginning to understand the theory in a totally different kind of way. This is the first time I've looked at a concept and gone all the way through.

Anytime he used any concept in the general nature of psychic overexcitability, we found out about it. This is what we have, and it's in your handouts.

It's a very interesting kind of thing, because he didn't just talk about overexcitability, but he had hyperexcitability, he had psychic excitability. There are a lot of different terms that he had, that he was working with.

What I want to point out to you that was so important to me to understand is in the early works, what you see about Dąbrowski is that he was a psychiatrist.

When you go back to this era, what you really see is his concern with the people he's working with—and these are clinical people. Overexcitabilities in those days were negative—there was nothing positive about them. They created the problem.

In these earlier times, the ones he was talking about were Psychomotor, Sensual, and Imaginational. He really thought those were very negative concepts. Now, what's really interesting is that this paper that's coming out in the next edition of Advanced Development, the journal. That is a brand-new translation of the 1938 article, which is the first time and the only time that Dąbrowski systematically talked about overexcitabilities and what they were all about.4

The thing that's interesting is there are only four that he recognized at that time. So psychomotor, sensual, affective, which we call emotional, and imaginational. The other thing that's very important is the distinction here that has been lost in the later works—this notion of the difference between global and narrow.

Every overexcitability can be narrow, and every excitability can be global. The distinction here is that, if it's narrow, it's going to be negative. It's not going to lead to development.

There are other words that we'll see he also used later in talking about that concept, but that's a very important concept from my point of view in terms of what's going on. This 1938 translation, which is coming out soon, is really a must-read. The other thing I want to point out is what was happening in these periods.

You don't have anything coming out between 1938 and basically 1958. Well, that's because of World War II and the communist takeover of Poland. It was during this time that he was more involved in trying to protect his clients and others that he put away in his clinic. Which he cleverly called tuberculosis, which kept people away.

What's interesting is that he ends the 1938 article with TBC, to be continued. Well, he didn't get around to it for a long time. But what are the books in the 50s and 60s about? They're interesting because they're very incomplete beginnings of the theory. They're not well developed. They're not articulated in a nice way that allows you to have a good understanding.

What happens is in the 70s, he begins to work with other people, and those other people are the ones who bring the structure and the explanation of what he was trying to say together. So, that's what the 70s really represent. Kawczak and Piechowski, working with him, provided the kind of structure that was necessary for us to be able to sort of understand the theory. But that's quite different from just understanding this major concept which he has from the very beginning all the way through, and that's overexcitabilities.

What we're saying is that to understand his theory, you have to understand that overexcitabilities are what lead to developmental potential. That's the direction, that's the cause, and so that concept of overexcitability is fundamental to the theory. The only other thing I want to say is that the handout that you have provides the timeline that Chris is going to talk about, and it also, at the very end, provides you with the references.

So, it's Chris's turn.

Chris: We've had such a good time working on this. Actually, a lot of things have changed since we first came up with the idea for this session because we didn't have the translation of the 1938 paper at that point, and we also didn't have a couple of the books that I'm going to mention that are in Polish.

In the last couple of months, we've learned about them, and we were able to see what was in certain editions of them that we weren't sure about yet, which was really cool.

I'm going to start by saying it's important to understand that nervousness was the original way to understand overexcitability. Nervousness was seen as negative, like Frank said. It was pathological.

We also investigated other terms that were used from that period. Neurasthenia was another one. So there's some overlap there. And neurasthenia was considered weak nerves—weak constitution—but Dąbrowski rejected that it was weak nerves. He saw it, obviously, as something that was positive. It's important always to keep this in the context of the time. No doubt one of the things that we want to show today is that there really is an empirical foundation for this theory. There's a lot of support for it in different ways, even from his contemporaries.

In 1937, you have “Psychological Bases of Self-Mutilation,” which was actually published in Polish in 1934. It was a dissertation. He did two actually, so he did a medical thesis on the psychological conditions for suicide. And then he did another dissertation on the psychological bases of self-mutilation. So this is where overexcitability comes from. From pain and suffering. When you see that in the theory, that's why. This is how he came to it. He had a friend who killed himself when they were teenagers. This is the foundation of his thinking.

So, in 1938, again, like Frank said, this is the first complete look at overexcitability. And there are four types. In 1938, he didn't include intellectual, but he did include it in 1964.

After those works, you see Nerwowość Dzieci i Młodzieży, which is Nervousness of Children and Youth.

In 1958, you see five types of overexcitability, although he doesn't talk about them in detail. That book is actually within Bill's materials on Dąbrowski, so I was able to look at it and tell that all five types were there, but he doesn't talk about them in detail.

The 1959 Społeczno-Wychowawcza Psychiatria Dziecięca book—there's a 1964 second edition of that. That was another place where he described five types.

We also found out his methods are described in the 1935 version of Nerwowość. So, we're learning more about his methods. In 1938, he talked about using a 100-item questionnaire for measuring overexcitability with 25 questions for each item. Which was very interesting because one of the criticisms of the OEQ-II is that Dąbrowski never would have done that, but he totally did. It's been so interesting to find out about these things.

In 1964, you have O Dezyntegracji Pozytywnej—On Positive Disintegration—which is the first real outline of the theory in Polish. There is an outline of the theory from 1959 in French, but this is a whole book, whereas the French version is just a paper. You also have the English Positive Disintegration.

And then, of course, in 1967, Personality-Shaping is sort of a translation of the Polish On Positive Disintegration, but a little bit different because he talked about different theorists in 1967. There are some minor differences between them.

That brings you through the 1960s. The theory hasn't been fully formulated yet, but all the ideas are there: unilevel, multilevel, the five overexcitabilities. He doesn't talk yet about the levels like we know them now. We also don't know about developmental potential yet. That was one of the cool things about using this software. Because I was able to figure out when he started talking about developmental potential. What that looked like. What was involved in it.

That's where I'm going to start today. By talking about the evolution of the concept of developmental potential and how overexcitability fits in. And what's important about overexcitability. Which is, as we've said, it's the driver of developmental potential because the dynamisms arise from the overexcitabilities. I will talk about all of that.

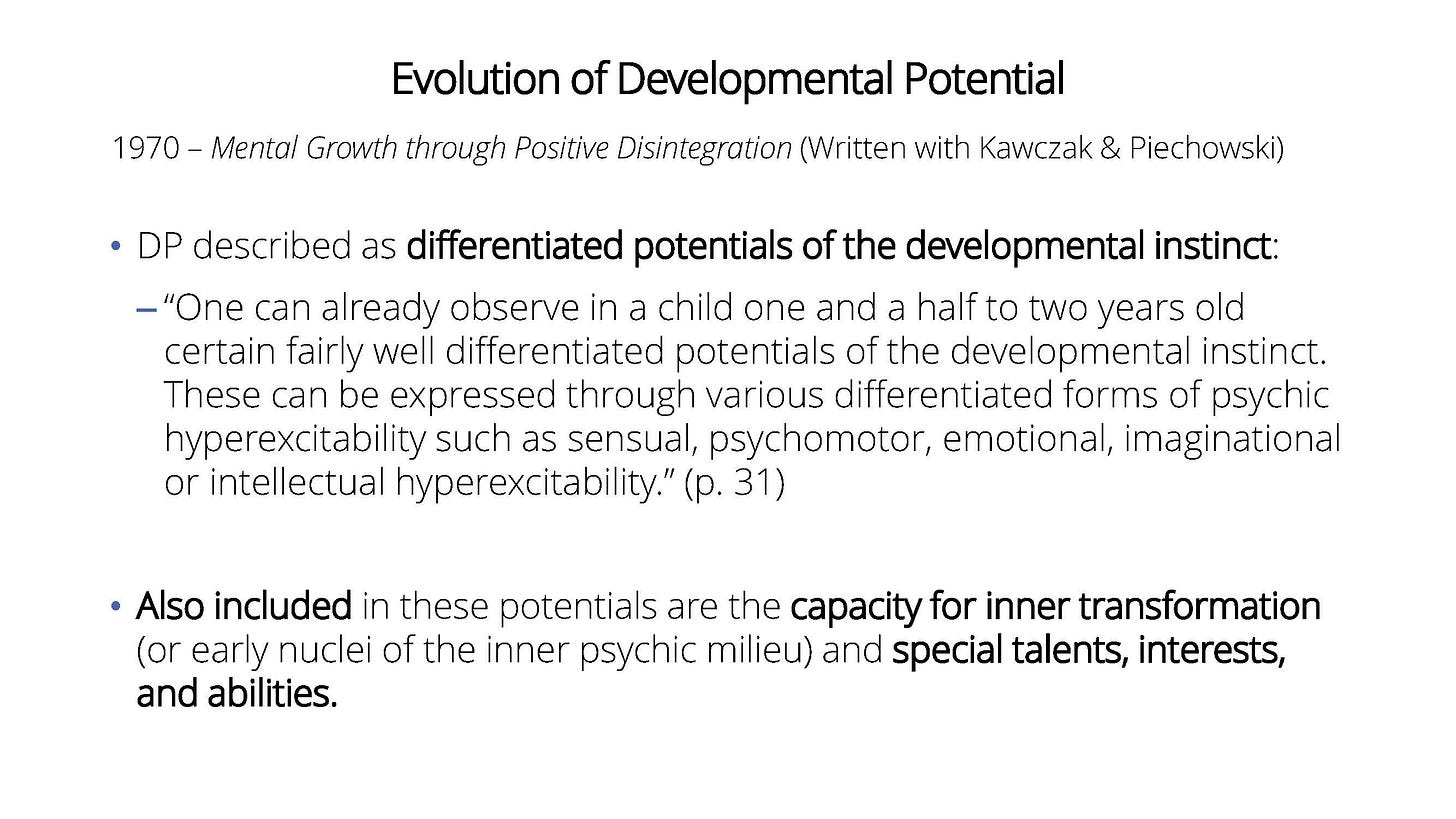

Developmental potential. In 1970, Mental Growth was the first book where that concept was discussed. But it's called “Differentiated Potentials of the Developmental Instinct.” The differentiated potentials are the five overexcitabilities.

In 1972, you see much more elaboration about developmental potential. Well, thanks to Michael, because we know that he asked him to elaborate, and explain himself, and you really see it in that book. The multilevelness project is the basis for the next two books, which are really the same books, but with some slight differences, because they were edited in 1977. But there's two volumes for each.

I have an archive where you can go and download each of the cases from this book.5 In Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions. So Volume 2, it is such a rich book. It has seven cases, and six of them were living people. The seventh case was Saint-Exupéry, who had died in 1944.

It's really interesting. They talk about the methods in detail, it's really cool, and I've never seen it cited in the literature. Michael has [cited it], I'm sure, but no one else. It's interesting, it's just disappeared. And yet, this book, it's over 400 pages long, is the empirical basis for the theory. He talks about his methods in the past, but this is where you see actual case material brought to the theory.

In 1970, in Mental Growth, they're differentiated potentials, and I picked this quote because it's a more simplistic view of developmental potential than you'll see in the future.

In this book, he implies that the dynamisms arise from the overexcitabilities: “It is from such potentials that arise the nuclei for the development of higher emotional attitudes. Nuclei for transcending one sided structures. for the development of authenticity, empathy, self awareness, and self control.”

I picked this quote because you see that he's talking about the positive developmental potential:

“The main form of the positive developmental potential are five kinds of psychic overexcitability namely, sensual, psychomotor, motor, affective (emotional), imaginational and intellectual. Each form of overexcitability points to a higher than average sensitivity of its receptors. As a result a person endowed with different forms of overexcitability reacts with surprise, puzzlement to many things, he collides with things, persons and events, which in turn brings him astonishment and disquietude.” (Dabrowski, 1972, pp. 6-7)

I'm going to talk about Psychoneurosis is Not an Illness. He talks about four types of developmental potential—not just positive, whether it's positive or negative.

In 1972, we learned that there is a negative developmental potential. Frank talked about the global and narrow types of OE. A narrow overexcitability is one that doesn't take over your whole psychic structure. If it's psychomotor, a narrow OE would look like tics.

It doesn't have the transformative elements that it would if it took over your whole psychic structure. In negative developmental potential, you may have an isolated, narrow form of overexcitability. Or you may have no overexcitability.

There's a complete absence of dynamisms. This has not been developed in the literature, obviously. The focus on developmental potential and overexcitability in gifted ed has been looking at positive or strong developmental potential. So, this is an area that is interesting to consider.

[As we learned in another session] Sometimes, highly gifted children don't have overexcitabilities that are evident to us. They may just not be manifesting in a way that we see on the Overexcitability Questionnaire. It's interesting to consider both that kind of situation and when you have somebody with a narrow overexcitability.

Limited developmental potential is next. In limited DP, you do see narrow forms. And you may see more than one narrow form even. Limited developmental potential lacks the transforming elements, or the multilevel dynamism… Both of these types of developmental potential produce a unilevel type of development. The next two are multilevel.

Strong developmental potential. In the description, in Psychoneurosis, you can see that he's talking about what we know as spontaneous multilevel disintegration, or Level III. Here, the overexcitabilities are a bit more complex. I'll show you differences in complexity later. The third factor is present. You see dynamisms are developing from the overexcitabilities, and they form the inner psychic milieu. Multilevel disintegration is underway.

Then, he had another type that he called Strong with Marked Developmental Dynamisms. And this aligns with Organized Multilevel Development, or what we would understand as Level IV. And here, the process of development has already moved into this conscious organized growth, and everything is firing—the dynamisms are there, you have a full complement of spontaneous multilevel. You see increased structural complexities.

Dąbrowski perceived some types of overexcitability as higher than others. And maybe not everyone agrees with that now, and maybe the literature may not [agree]. It's interesting to think about a big three, or psychomotor or sensual not being as developmentally positive.

It's interesting to consider all of that in light of decades of overexcitability research since he made these conclusions. He did consider that psychomotor and sensual didn't have the transformative elements that you see in the so-called big three. Because they're the ones that are coming together—cognitive [intellectual], emotional, and imaginational—that's what's producing the dynamisms.

“A person manifesting an enhanced psychic excitability in general and an enhanced emotional, intellectual, and imaginational excitability in particular is endowed with a greater power of penetration into both the external and the inner world. He has a greater need to see their many dimensions and many levels, to think and reflect upon them. These forms of overexcitability are the initial condition of developing an attitude of positive maladjustment to oneself, to others, and the surrounding world.” (Dabrowski, 1972, p. 65)

You see the increased complexity here when he's talking about overexcitability as a part of developmental potential. He also gives examples in this book of what strong developmental potential looks like in a child:

“One six-year-old girl when asked by her mother whether she did not get tired by dancing, answered, “Mother, I don't get tired because I don't dance. It's only my feet who do the dancing.” In this expression, we can see, besides a marked refinement of thought, a nucleus of the development of the inner psychic milieu, initial forms of the dynamism subject-object in oneself, and a developmentally significant dualistic attitude (a manifestation of different levels of experience).” (Dabrowski, 1972, pp. 8-9)

So, he's contextualizing, and he talks about what it looks like in a child, what it looks like in someone with psychoneuroses. He really is bringing it together here. But then, interestingly, at the same time, they were working on the multilevelness project and actually took this material that they gathered and provided more of a foundation for what he had come across from his observations and his clinical practice.

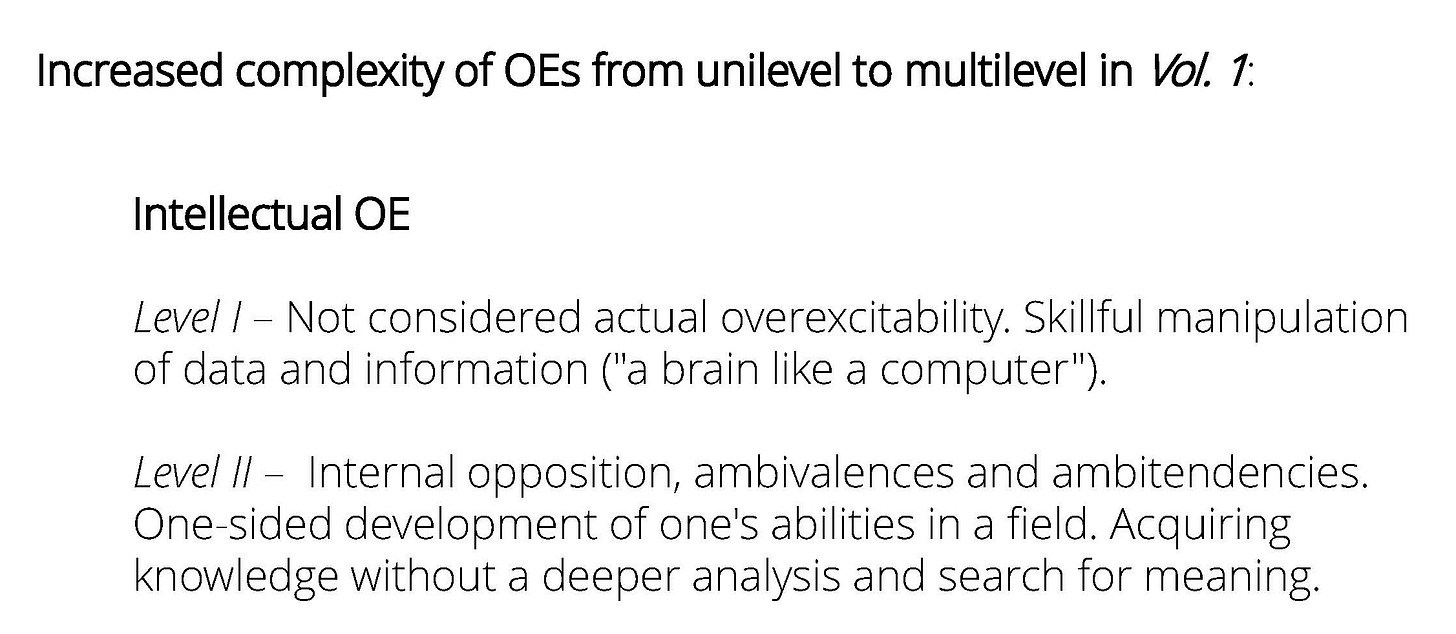

Volume 1 has levels of overexcitability presented.

The example I used is from intellectual. Someone with intellectual overexcitability at Level I—it's not really overexcitability. It's that they have a brain like a computer. You may be highly gifted and do incredible things with your brain, but it doesn't transform you.

The developmental potential here is described in terms of the three factors of development, too, which is interesting because, in Volume 1 in 1977, it's not portrayed that way, which is partly because of Michael's editing. It's interesting to think about the interpretation of these concepts and how they evolved even within the 70s when he was working with other people.

Thanks to Michael for this because he gave me this little quote right before we left for the Congress. Here is a place where we see explicit mention that the dynamisms arise from overexcitability.

“The five forms of overexcitability undergo extensive differentiation in the course of development. One of its products are the developmental dynamisms. The intra-psychic factors which shape and direct development.”

There are multiple books where you can see that the dynamisms arise from OE, and I'm stressing this because you see frequently in the literature [the question], “What's the relationship between these concepts? We don't know.”

But no, we do know. These things are all here. It's just a massive volume of information.

“In general, we may suppose that in the sequence of development dynamisms are the product of differentiation of forms of overexcitability. Certainly, such dynamisms as dissatisfaction with oneself, inferiority toward oneself, disquietude with oneself, feelings of guilt, responsibility, empathy, are primarily derivatives of emotional overexcitability. They are its varied and more evolved forms.” (Dabrowski & Piechowski, 1977, p. 243)

I think it makes a lot of sense to think of it that way. When you're young, and you're struggling with emotional overexcitability, if you have a really strong developmental potential, it's going to produce dynamism.

When you think about the relationship between giftedness and overexcitability, gifted people reach milestones earlier. So, when you have advanced cognitive abilities, it looks different than it does in typically-developing people.

I know from my experience that that's how it is when you're young. Sometimes, you start to envision things in different ways without even understanding how it looks for other people.

There's so much to explore here. It's exciting. I think that's why we've had such a good time working on it.

In the first Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions, Volume 2 came out in 1972, and Volume 1 came out in 1974. Those books are available from 1996; they were reprinted in 1996. Then you have Theory of Levels of Emotional Development, Volumes 1 and 2, which are almost the same.

They're very similar. I compared the documents with software that compares the text to see what's been changed, and very little was changed. Michael made some editorial decisions. Well, he had to, because the publisher requested that it was not so long.

In Volume 2 in 1977, you only have four cases instead of seven. But that's why—because [the two volumes make up] a 450-page book they wanted to be shorter. He couldn't include all the cases. This is unfortunate, but at least now we can look back at the earlier version.

I already mentioned that in 1977, there was less emphasis on the three factors of development. There was no mention of the global and narrow OEs. In 1970, you do see mention of global and narrow, but the phrasing is different. So, it's called all-inclusive for global and confined for narrow.

This is another example of concepts that are hard for people to understand. The autonomous processes are represented by multilevel dynamisms—that's the third factor of development.

There are several instances where he uses words interchangeably: nervousness, psychic overexcitability, third factor. And then, of course, there's a third factor, dynamism, and a third factor of development, just to make things complicated for you. And they're used in different ways.

Definitely one of my goals is to go through and pull out these concepts that people are familiar with and show where they were used, in what ways they were used. And once we have that kind of foundation, it'll make it easier for people to do research, I think. These things will be clarified.

Now, I'll go into the complexity of overexcitability and changes from unilevel to multilevel process in Volume 1.

As I already said, at Level I, it's not real intellectual overexcitability. It's a brain like a computer.

In Level II, very familiar terminology: ambivalences and ambitendencies. But here, you can see one-sided development because, again, it's narrow. And so when you have this narrow intellectual overexcitability, it may not be enough to help someone develop their interests beyond one passion. Acquiring knowledge without a deeper analysis and searching for meaning.

So, at Level III, now we have mention of the dynamisms of spontaneous multilevel disintegration. It enhances the development of awareness and self-awareness, which are obviously critical to development. Here, it develops the need for finding the meaning of knowledge and human experience. Conflict and cooperation are associated with emotional overexcitability and the development of intuitive intelligence. Intuition was really important in this theory, even though it isn't a dynamism, but it could be.

At Level IV, things are even more complex. Intellectual interests are extensive and universal. There's a great deal of interest in objectivization of the hierarchy of values. Inclinations towards synthesis. Interestingly, Michael pointed out that when Dąbrowski talks about synthesis, he's saying the same thing as when he talks about reintegration. That's just another example of the terms that are sort of interchangeable.

In the 30s, he had the 100-item questionnaire. Then there was the multilevelness project, and obviously, in between, there were his extensive clinical observations in his work. In the multilevelness project, another interesting thing that Michael has been able to inform me about is the fact that when he was rating the material of the autobiographies and the verbal stimuli, coding for overexcitability wasn't even a priority.

They were looking for dynamisms and functions, and he was able to realize while he was doing that coding that he was also seeing overexcitability as well.

From that, he developed the Overexcitability Questionnaire, which people are familiar with. That was the original open-ended questionnaire developed in 1973. There were 46 questions, and Michael has an appendix in Mellow Out with the original open-ended version of the OEQ, and it has two revised versions.

He created that instrument from the data that was collected for the Multilevelness project. The OEQ-II was created from the original Overexcitability Questionnaire. We've already been talking about how to think about things like global and narrow with the OEQ-II and what the future of measuring overexcitability will look like.

I would love to collect responses from the original open-ended OEQ from people who have done overexcitability research to make a database. There are decades of research about overexcitability. We just need to pull it together and make it available. I've already started sharing data in a data repository, and I'm going to continue doing that as I collect it.

Frank: I just wanted to make one other comment. One of the principles that Chris works with is this concept of scientific transparency. That's a fundamentally different kind of notion about what we should be doing as scientists, and how we operate in terms of publication and presentation. So, I just wanted to make that one little point. So, you see what I like working with her.

We didn’t stop studying overexcitability and developmental potential after this presentation. We kept going and worked to produce The Origins and Conceptual Evolution of Overexcitability, which was published in 2021. [Download it here.]

I wrote about my first exposure to the theory in Interesting Quotes, Vol 2. I’ve removed the paywall, so it’s accessible from now on.

Michael published his keynote Lives of Positive Disintegration in Volume 18 of Advanced Development Journal.

Click here for a PDF of the conference proceedings.

Download the translated 1938 paper, “Types of Increased Psychic Excitability.” Michael completed the translation in May 2018 and shared it with us.

That archive no longer exists, but you can access the data sets at Mendeley Data.

Interesting read.

Would you mind giving an example of “Develops the need for finding the meaning of knowledge and of human experience”?

It’s part of the text that explains what happens when the complexity of OEs increases at level III of Intellectual OE.