NAGC 2017: Honoring Dąbrowski's Mission

Piechowski's Contributions to the Theory of Positive Disintegration

At NAGC 2017, I presented my literature review on the English works of Dąbrowski and Piechowski. Sadly, it was a combined session, so I only had 30 minutes rather than an hour to discuss an enormous amount of work and decades of research.

In preparation, I wrote a 9,534-word paper for that conference session, which remains unpublished. I will include parts of it here, along with some slides from the session. The references are available as a PDF at the end of this post because I can’t take time this week to produce a proper reference list from these excerpts.

I started the paper with introductions:

“The theory of positive disintegration (TPD) is a theory of human development created by Kazimierz Dąbrowski (1902-1980), a Polish psychiatrist and psychologist. Originally developed in Poland, and fully formed during his years working in Canada, Dąbrowski's theory found a home in the field of gifted education, due in large part to Michael Piechowski's elaboration of the concept of developmental potential (Piechowski, 1979, 1986). Piechowski, also from Poland, first met Dąbrowski in Canada fifty years ago in Edmonton, Alberta, and he recognized that the observable components of developmental potential, known as overexcitabilities (OEs) in TPD, were helpful concepts in understanding the often intense reactions of gifted children (Piechowski, 2014a).”

Next, I shared some of why I came to the theory, and I included one of my favorite lines from Michael’s book Mellow Out:

The session was partly inspired by a problem I’d observed online, especially on social media, which was a constant stream of negativity about Michael by mostly one person. This person’s public questioning of Michael’s work went well beyond an academic discussion and into personal grudge territory.

What concerned me were the implications of this relentless criticism both on the literature in gifted ed and on people’s views of the theory. Personally, I was turned off by his behavior on Facebook immediately, and I could imagine how many other people joined his group, saw his negativity, and walked away with a poor impression of the Dąbrowski community. I took it upon myself to push back.

Once I was seriously studying the theory, I realized how few people actually read the original work by Dąbrowski. Therefore, I perceived my work in 2017 as educating others from what I had learned.

I presented the details of my literature review, which was deep and extensive. In retrospect, I can easily say that the groundwork I did in 2016-2017 gave me a solid foundation.

From the unpublished paper:

“The goal of the literature search was to locate the entire body of English work by Dąbrowski as well as Piechowski. One barrier that has long confronted scholars interested in studying the theory is the lack of availability of Dąbrowski's English works. Initially, I was determined to acquire the print versions of Dąbrowski's books, but I was unable to locate all of the books for sale. Ultimately, I paid for his works in portable document format (PDF), from the one place from which they are available. A benefit of purchasing PDF copies of the books has been the ability to use computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS) in the analysis of the texts. The CAQDAS chosen for this review was QDA Miner (version 5.0.5), with the WordStat module (version 7.1.8), by Provalis Research.”

I indeed resisted purchasing the digital materials because of what I described above on Facebook. I felt so much resistance to contacting him. But once I had those materials, I dug in and spent months reading PDFs and bringing them into my project files in QDA Miner.

There were three project files with source material about the theory, including Dabrowski’s English works, collaborative work by Dabrowski and Piechowski, and Piechowski’s work. Click here to download Appendix A with lists of the documents in these project files.

Next, I discussed the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review, which you can download here in Appendix B. Here are my thoughts from the paper:

“Decisions concerning the inclusion and exclusion of documents were often informed by the search results for conceptual terms in QDA Miner. When there was significant overlap (repetitive text) between published works and unpublished conference papers, for instance, the conference papers were eliminated from the study. Numerous documents have been made available for this review to support the assertions made concerning the theory and its elaboration by Piechowski. In the spirit of transparency in research, I have provided as many reproductions of my project files and data as possible. The search strategy for this review was based on the two authors, Dąbrowski and Piechowski, rather than for concepts related to the theory itself. Therefore, I relied heavily on lists of publications for Dąbrowski, from multiple sources including websites and bibliographies.”

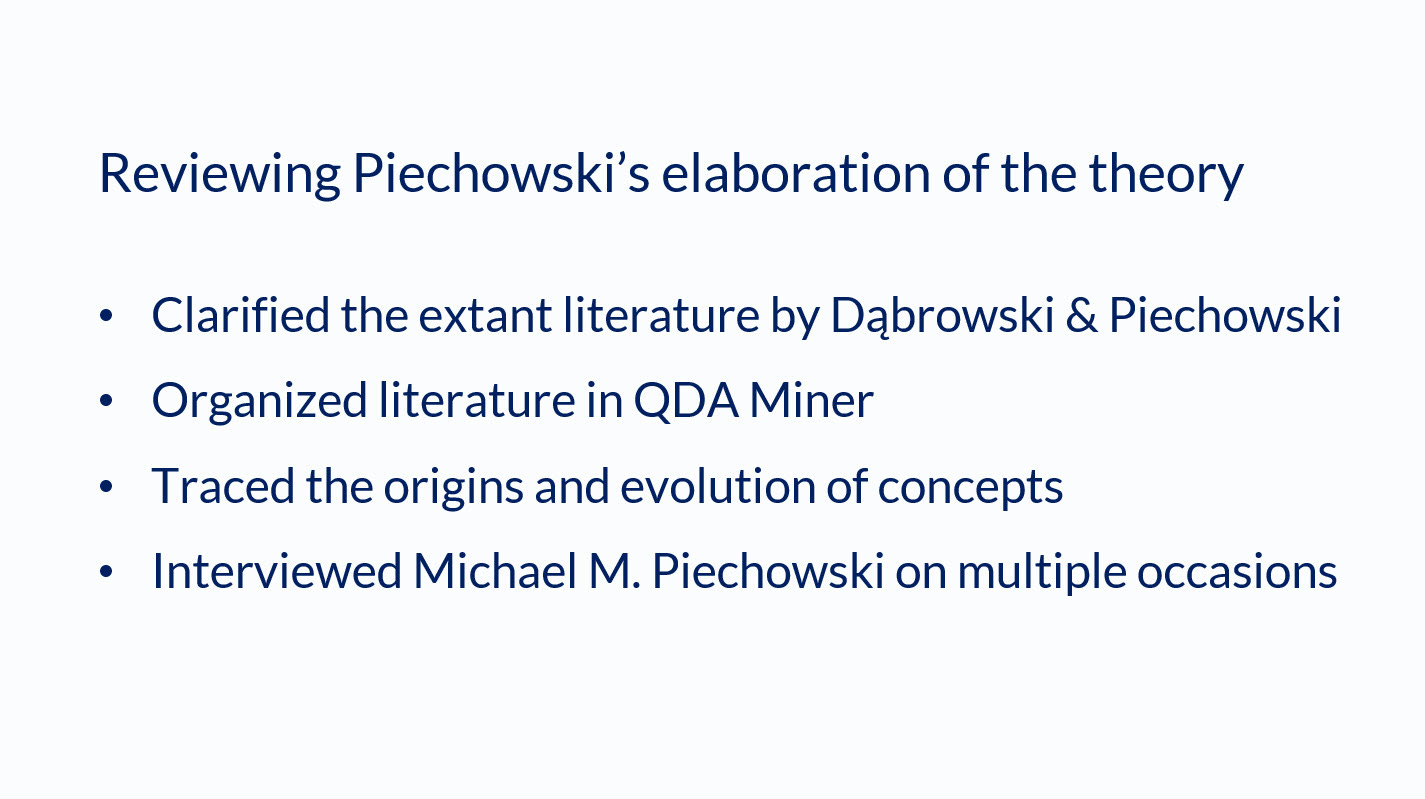

I included a slide describing my lit review process.

This is what I included in both the paper and my session about the process:

“The initial goals of the review were to clarify what literature exists by Dąbrowski, as well as Piechowski, and to provide a clear timeline of the evolution of theoretical concepts. As I uncovered materials related to the theory, I wondered why there were so few references in the recent literature originating from Piechowski's substantial body of work (e.g., Harper & Clifford, 2017). Like Dąbrowski, Piechowski is from Poland, and English is not his first language, but his facility with the language is better than most native speakers. It seemed puzzling that people are writing about the theory and citing from Internet discussion groups rather than Piechowski, and I began to investigate this issue in the literature and also in online discussions concerning the theory. This led to the second goal of resolving tensions and disagreements which have developed both within and outside of the literature (Mendaglio & Tillier, 2015; Piechowski, 2015; Tillier 2009a). I hope to make clear for other researchers that Michael Piechowski is not a heretic who extracted a single concept from the theory (overexcitabilities) for his own gain.”

The above goal came from my observations of the gifted ed literature and online behavior. The other came from my experience of researching and making sense of outdated terminology, as well as getting a handle on what was written when, and resolving translation issues:

“Another goal of this review relates to language and the clarification of theoretical concepts. The terminology used by Dąbrowski (1937, 1964, 1967) feels dated because words like neurosis and psychoneurosis have long been out of use. The first original text I read of Dąbrowski's was Personality-Shaping through Positive Disintegration, which I found dense… At the time, I did not have a clear sense of when Dąbrowski's books were produced, and their order, and therefore I did not realize that Personality-Shaping is largely a translation of the first book about the theory, which was published in 1964, in Poland… Despite these issues, Dąbrowski's ideas are worth saving from obscurity.”

Appendix C included lists of publications I compiled of the work of Dąbrowski and Piechowski. (Please note that these documents haven’t been updated since 2017, so the references are APA 6th edition and out of date.)

Next, I described my techniques for analyzing the texts I studied.

“For this review, a variety of strategies and techniques for qualitative data analysis were employed. In the review of texts, I used word counts (by document, author, and keyword), word frequencies, keywords-in-context, and phrase extractions, as one of the benefits of qualitative analysis techniques is in the illumination of patterns within the text, using tools for contextual retrieval (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2008). These results were used to identify and track the origins of keywords to better understand the evolution of concepts within the theory. I created documents based on text retrievals, and retrievals by query, in which I highlighted segments of text and searched for other blocks of text with similar expressions, grouping related concepts and analyzing them outside of their original contexts.

For the conceptual synthesis, I used secondary data analysis when reviewing the examples of OE from both Dąbrowski & Piechowski (1996), and Piechowski (2014a), and examined this data from open-ended questionnaires in an effort to determine the place of OE within the theory, as well as Piechowski's fidelity to Dąbrowski's interpretation of phenomena. In the case of the Multilevelness Project subjects, from Dąbrowski & Piechowski (1996), I coded each instance of an expression of a dynamism, or overexcitability, and also noted the level of each identified expression. Two documents were created with the results for OE, from Dąbrowski's Canadian research, as well as many ideal examples of OE which were collected by Piechowski with the first version of the Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ).”

Writing about what I did in the 2017 review feels somewhat astonishing to me now, in retrospect. It was an enormous amount of work, and it occupied all of my energy. On top of the work I described in the paper, I was also constantly writing to Michael and sharing my thoughts about everything.

It must also be acknowledged that I started learning Polish at the very end of February 2017. I spent an enormous amount of time that year in Rosetta Stone, Duolingo, and writing to Michael with Polish questions. I completed the entire Rosetta Stone course in March-April 2017 and spent well over 100 hours that spring immersing myself in a new and unfamiliar language.

Last week, I showed my son my Duolingo stats because he’s got an impressive streak going with French in their app. The last time I took a screenshot of my stats was in early 2021. Currently, I have more than 60,000 XP on Duolingo, and I’ve completed the Polish tree twice.

Back to the review efforts… The final appendix from NAGC 2017 was Appendix D—Timeline based on Project Files in QDA Miner. I thought of creating a post from it, but I’m going to wait until I have the time and space to format it nicely. In the meantime, a PDF version can be downloaded.

I also created a timeline on TikiToki, which I remembered earlier this fall. I actually made two online timelines, but I didn’t leave any evidence of where the second one can be found, and sadly, I no longer remember.

When I visited Michael in September 2017, I showed him the timeline on his Mac, and he immediately stood up and went to get a book from his shelf to check my work. A photo exists from that day, capturing the moment, but I’m not sure Michael would want me to share it here. And since he’s a subscriber, I will err on the side of caution.

Once I made it through the description of my review process, I could discuss the theory and Michael’s elaboration.

There was a slide with this quote from Michael’s paper “The Roots of Dąbrowski’s Theory”:

“Dąbrowski’s mission in developing his theory was to depathologize the characteristics of intense agonizing experience and instead to show that what used to be called psychoneurosis and thought of as mental illness is, in fact, a process of personal growth. Positive disintegration may look like an illness, and it feels like an illness to the individual suffering through it, but it is a natural process of inner transformation just like the caterpillar turning into a chrysalis that through profound inner upheavals turns into a butterfly. (Piechowski, 2014b, p. 38)”

Some of the issues I’ll be discussing in this year’s session were on the agenda back in 2017. For instance, in my slides, I addressed Myth #3 from my post earlier this week.

Here’s more from the unpublished paper:

“A detailed elaboration of overexcitability, which is one component of Dąbrowski's concept of developmental potential (DP), is the first aspect of the theory applied to the field of gifted education by Piechowski (1979, 1986, 1989). Developmental potential is made up of overexcitabilities, special talents and abilities, and the capacity for inner transformation (Piechowski, 2003b). One misconception which can be found on the Internet as well as in the recent literature is the assertion that one cannot study the OEs outside of the framework of the theory (Mendaglio, 2012; Mendaglio & Tillier, 2006; Tillier, 2009a; Vuyk et al., 2016a, 2016b). A careful analysis of the evolution of overexcitability in Dabrowski's original works indicates that such a belief is inaccurate. The concept of overexcitability preceded the final formulation of the theory, and it does not require other concepts from TPD in its measure or understanding. Mendaglio (2012, p. 215) claimed that OE is "an integral part of Dąbrowski’s TPD…the conceptual source of OE,” yet the concept of OE predates the theory by decades (Dąbrowski, 1937, 1938, 1959). Dąbrowski's theory followed the elucidation of the overexcitabilities, not the other way around.”

There are many errors and inconsistencies in the literature, and I’m looking forward to discussing them yet again at NAGC 2023. I hoped to clear some of them up with the paper I wrote with Frank on the origins of OE, but I’ve discovered that people are often unswayed by data and evidence, which is unfortunate.

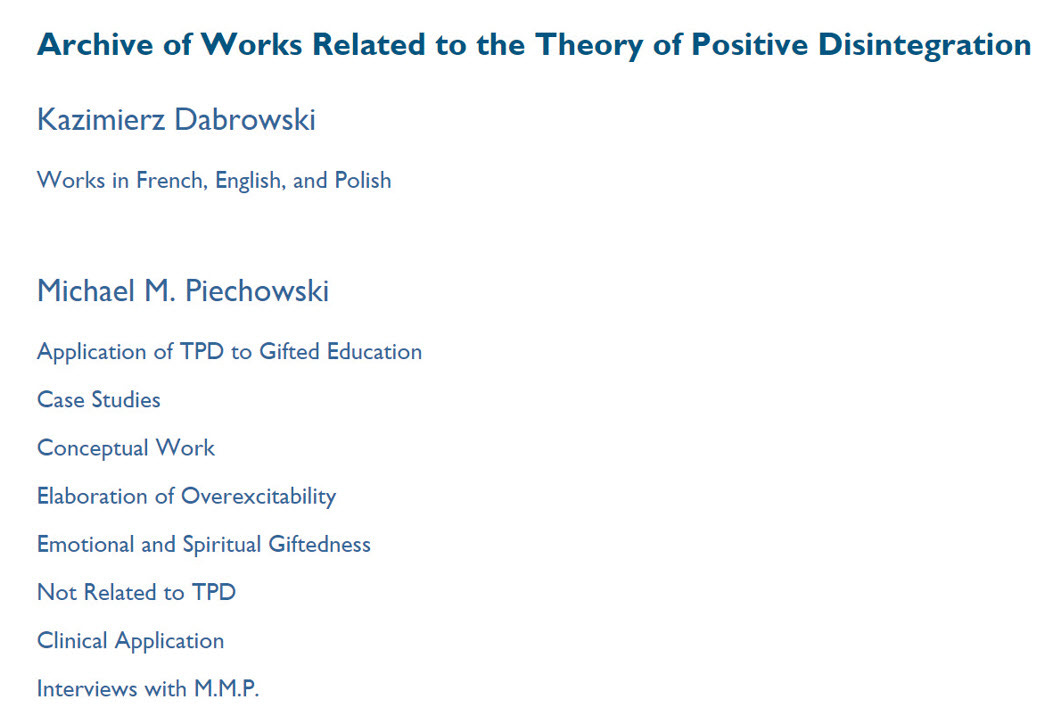

Another thing I did to prepare for NAGC 2017 was create an online archive.

It’s no longer available in the same place, but it can be found on the Dabrowski Center website now instead.

In the paper, I talked about Michael’s elaboration of OEs in gifted education. I described the development of his open-ended OEQ and how that work provided a foundation for modern instruments.

“Piechowski (2014a) also created an instrument to study the OEs during his second doctoral program which he called the Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ). The original version of the open-ended OEQ had 46 questions, which Piechowski developed based on the data that he had rated for Dąbrowski's Multilevelness Project. In the following years, Piechowski's colleagues and graduate students helped collect data (e.g., Lysy, 1979; Silverman & B. Ellsworth, 1981) and the OEQ was refined and shortened to 21 questions (Lysy & Piechowski, 1983). Based on this work, Piechowski (1979, 1986, 1991) elaborated on OE significantly, describing each of the five types in detail.”

I also wrote for the first time about developmental potential, dynamisms, and the inner psychic milieu.

“As mentioned above, the OEs are not the sole indicators of a positive DP, and it includes also the "capacity for inner transformation" which refers to dynamisms. While an individual's talents and abilities, and the five forms of overexcitabilities, can be observed and measured, the multilevel dynamisms are not easily observed. The capacity for inner transformation means that one possesses the germ, or nuclei, of the inner psychic milieu. This has been described as a transforming characteristic, from which one creates an autonomous hierarchy of values, or a sense of a higher and lower within oneself, leading to the active, deliberate pursuit of one's higher self or personality ideal (Lysy & Piechowski, 1983, Robert & Piechowski, 1981).”

I also tried to connect these constructs with the definition of giftedness as asynchronous development:

“The inner psychic milieu is simply an individual's experience of dynamisms, in the process of positive disintegration, or development. The existence of such an inner experience indicates that multilevel development is taking place, that a budding personality is undergoing a potential transformation. The process of development, fueled by OEs and dynamisms, takes place within the inner experience, and Dąbrowski and Piechowski have both called for it to be nurtured and celebrated, not pathologized. Similarly, the asynchrony definition of giftedness, put forth by the Columbus Group, also honors the inner experience and incorporates the construct of overexcitability from Dąbrowski's theory (Morelock, 1996; Neville, Piechowski, & Tolan, 2013; Silverman, 1997). The Columbus Group developed the asynchrony definition after a Dąbrowski workshop at Ashland University (Piirto, 2010; Silverman, 2009).”

Working on the paper with Michael was both stressful and exhilarating for me. It was stressful because I couldn’t help but feel anxious about what he would think about my attempts to describe the theory and his work, and exhilarating because it was so much fun for me to have that connection with him.

There was more work done that I could link to in this post, but I’m going to hold off because this already seems like a lot. I’ll save the data I coded and sorted with QDA Miner and the documents with excerpts from the works of Dąbrowski and Piechowski for another day.

I enjoyed reading work from critical psychology while working on the 2017 review and thinking about where the theory might find a home in other fields:

“In his discussion of the use of power in psychology, Prilleltensky (2008) describes the inherent problem of internalizing labels in which "oppression can be directed inwards, towards oneself, towards family members, or towards others in the community. Finally, power can be used to resist oppression and pursue liberation" (p. 121).”

I’m going to wrap up this post with the final conclusions from the unpublished paper:

“Piechowski's (2014a, 2014b, 2015, 2017) recent work has provided many rich examples of how we might move the theory forward within the fields of education and psychology. It is my belief that an urgent need exists to liberate the concept of OE from the field of gifted education. Although no one intended for such a consequence to occur, the connection between giftedness and OE has been an obstacle in the application of the theory outside of the field. Until there is no stigma associated with the word gifted, this problem will persist.

This paper is my declaration of intent to work toward situating the theory of positive disintegration within the field of psychology, and I cannot do this work alone. If you have come to this presentation because of an interest in OE, please know that there is a world of opportunities for studying this construct as well as the theory to which it is connected. Dąbrowski and Piechowski have provided everything we need to move forward on a path to rethinking how we approach the most basic concepts of what it means to be human. It is up to us to take their work and build on it. Honoring Dąbrowski's mission means learning to value tolerance and diversity of thinking, and most importantly, protecting ourselves and our children from the real harm of being misunderstood. It is only through our example that we can expect children to be kind, to think critically, and to understand the power of their own strength and will.”

Next, I’ll share slides and thoughts from my session at NAGC 2020 on “The Origins and Conceptual Evolution of Overexcitability.”

Click here for the references from the unpublished paper. The style guide used was APA 6th edition.

Note: In the voiceover for this post, I chose not to read most of the citations.