The First Conversations

Looking back at early interviews with Michael M. Piechowski

This post marks an important turning point for me. After years of writing privately and building an extensive personal archive, I’m finally ready to share more publicly about my method. These reflections on two early interviews with Michael M. Piechowski are part of a larger project—one grounded in my lived experience and shaped by years of relational inquiry.

The interviews took place on September 7 and 8, 2017, during my third visit to Madison, Wisconsin to spend time with Michael. We sat in his home, surrounded by books, music, and papers, and recorded two long conversations that still carry resonance today. They were not formal research interviews. They were part of something much more personal: the unfolding of a relationship, a shared inquiry into meaning, and the deepening of my own developmental process.

Through close attention to my journals, letters, transcripts, and imaginal material, I’m developing an approach to research that is personal, developmental, and rigorous in its own way. This is the first of many pieces that draw from that archive to illuminate how the theory of positive disintegration has come alive in my life.

For years, I avoided these recordings. I remembered talking too much, filling the space, and trying too hard to showcase what I’d already learned. But now, nearly eight years later, I’m seeing them through a different lens. What once felt awkward now reads as earnest. I see a younger version of myself reaching across the gulf of generations, trying to ground myself in a theory that was already reshaping how I made sense of my life.

These interviews with Michael felt like initiations. I had already sensed that our connection would carry weight and that it would shape me over time. I came prepared to gather information, but I was also stepping into something personal and meaningful, even if I didn’t yet understand what it was becoming.

At the time, I didn’t have the language I have now. I only knew that something came alive in me when we talked. I could feel the friction of disintegration—my mind had caught fire, and my heart was expanding beyond its limits. More than a spark, it was a surge of becoming.

Reading these transcripts now, I’m witnessing a period of emergence.

What I didn’t fully grasp at the time, but see clearly now, is that I was in the midst of a profound disintegration. This was not an abstract idea, but a lived experience that reached into every part of my being. My emotional intensity, my imagination, my hunger for meaning—all of these were in motion, pulling me inward and forward at once.

I lacked the vocabulary to adequately describe concepts like the third factor or subject–object in oneself. I also hadn’t yet realized that I was moving through a spiritual emergence. My consciousness was shifting in ways that felt both destabilizing and sacred. The boundaries between past and present, self and other, inner and outer, were softening. The imaginal world I had carried for so long was beginning to show up in waking life. The connection I was forming with Michael was part of that transformation.

Now, I can see how much was already alive within me. I was experiencing the theory from the inside, not studying it from a distance. These conversations captured a moment when something essential was beginning to take form. I spoke from a place that was still becoming, and I spoke with the urgency of someone on the threshold of change.

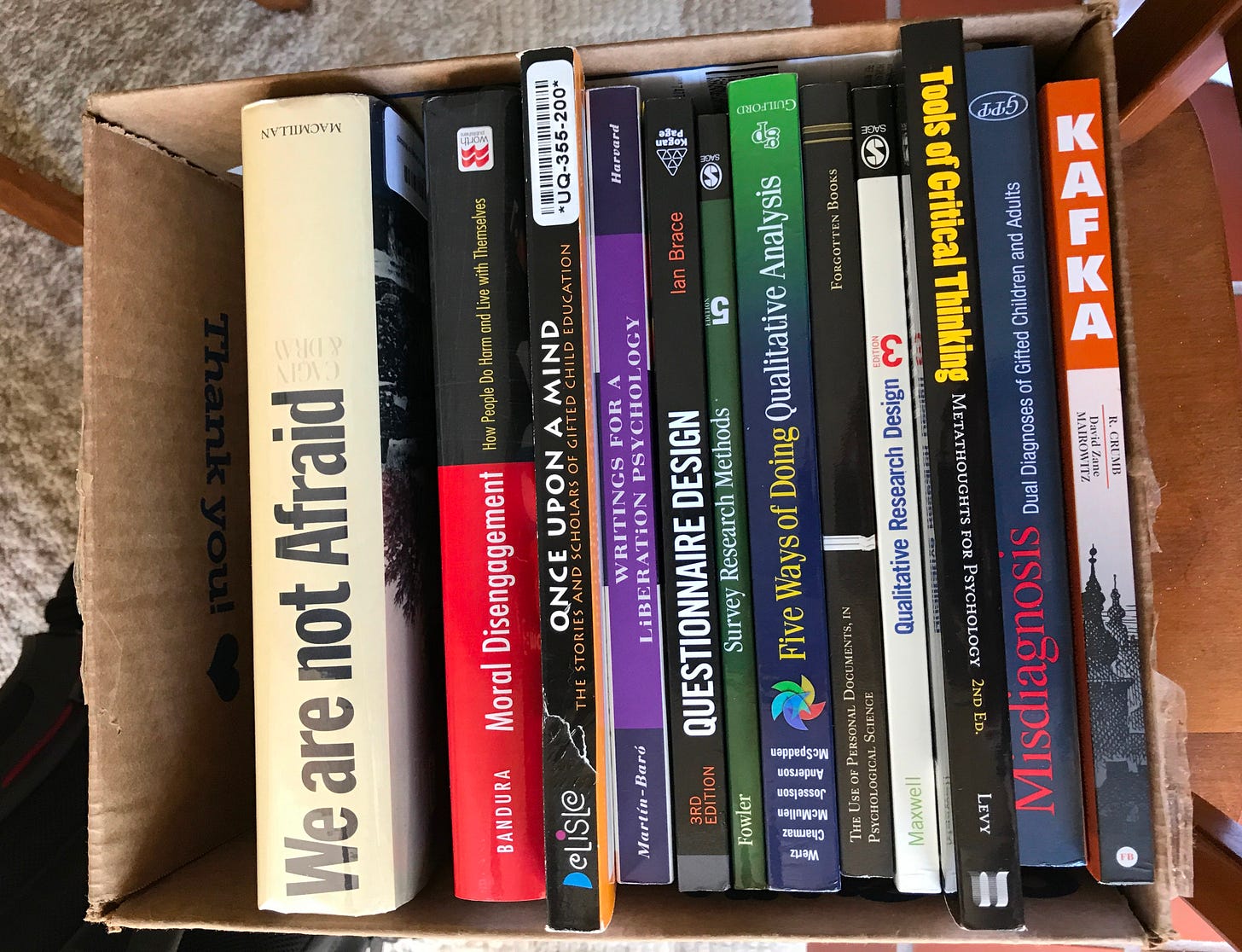

While visiting Michael, I took notes while we discussed papers, books, and my literature review for NAGC, which I’d been working on all year. I’d produced a full-length paper that I never submitted for publication, but it captured well where I was at the time. The dining room table was covered in papers—mine, his, and whatever books had ended up between us.

I remember watching him read with his head bowed, and thinking how surreal it was to be sitting there with him. But it didn’t feel formal, it felt ordinary and human. We’d eat, talk, drift in and out of quiet. Being there gave me something I couldn’t get from theory alone. It gave me context. And it allowed us to settle into something real.

Interview One: Spark and Friction

That first conversation was intense and uneven. I came in with force—hungry to connect ideas, challenge assumptions, and bring my lived experience into the heart of the theory. I didn’t always know how to pace myself. I talked a lot. I pressed. I reached. But what I see now is someone testing the ground. Figuring out what could be said, and how far I could go.

Michael was patient, but cautious. He received my enthusiasm with a kind of guarded receptivity—present, curious, and careful. At the time, I took that as a signal to dial back. I thought I was overstepping. Now I see a meeting of two different developmental styles: mine, dialogic and fluid; his, precise and protective of the structure he helped build.

That dynamic surfaced when we talked about the levels. I questioned the linear model, floated alternatives, and wondered about simultaneity. Michael steered us back toward structure, sequence, and theoretical integrity. We weren’t in conflict, but we weren’t fully aligned either. There was something productive in the tension between us.

There was vulnerability, too. I brought myself in and talked about misdiagnosis, shame, the pain of being seen as disordered when what I was experiencing was intensity and inner complexity. Michael didn’t flinch. He listened. That, in itself, was transformational. He stayed present. He gave me space to stretch out and share my vision, even when it was messy.

Interview Two: Memory, Mutuality, and Shared Ground

When we spoke again the next day, the energy felt different. I wasn’t holding quite as much urgency, and the space between us felt more open.

This time, I brought a different kind of curiosity. I wasn’t focused on testing boundaries. I was trying to understand where the theory came from and who shaped it. I asked about Dąbrowski’s imagination, about Maslow, about Susanne Langer, and even whether he and Sal Mendaglio ever talked on the phone. These might have sounded like small questions, but they were part of a deeper effort to understand the human relationships behind the ideas.

At one point, I asked Michael what Dąbrowski was really like, beyond the image of a gracious European intellectual. I wanted to know how he lived, how he connected with others.

Chris: I wanted to know more about what Dąbrowski was like. Again, I know you said that he was a gracious European gentleman, with a commanding presence, but what else can you tell me? Because I don't really know what those things mean. What was he like? Was he funny? Was he demanding? We know that he was demanding, because you've described the way that he expected a lot of the people who worked with him, or for him.

Michael: Well, the best side of him was always when he received people at his house. He liked gatherings. And his wife prepared good things to eat, whether a minor thing or dinner. So he liked to have a group of people, in which you could discuss all kinds of things. So these were very nice times. We were invited to the house for Christmas and Easter.

It’s a small moment, but it stayed with me. Hearing Michael describe Dąbrowski hosting conversations at home—surrounded by people, food, and open dialogue—gave me a different sense of where the theory came from. It wasn’t developed in isolation. It was shaped through relationships and shared experience.

That image reminded me of the times Michael has welcomed me into his home over the years. We’ve shared meals and spent quiet time together. Those moments were generous in their simplicity. They’ve stayed with me. They remind me that this theory doesn’t live only in books and papers. It also lives in connection, in presence, in the way we show up for each other.

When I asked Michael whether Dąbrowski ever spoke about his own imagination, he said,

“One statement that I remember is when he said he could see everything like on a stage while talking about dynamisms. That says a lot about his imagination.”

He shared more as we continued: memories, relationships, pieces of the history that had shaped both him and the theory. There was laughter and more ease compared to the day before. It felt like a genuine exchange.

I entered the conversation differently this time. I wasn’t confessing or searching for validation—I was grounded. I shared a story about the inner sense of mission I had carried for as long as I could remember, even through the most tumultuous and searching years of my life. Michael didn’t analyze or interrupt. He listened, and that was enough. His quiet acknowledgment affirmed what I already knew deep down: the theory had become part of how I understood myself. It shaped my inner landscape and gave language to experiences I had long struggled to articulate.

When I spoke about my sense of mission, even in the chaos of my earlier years, I put it this way:

“Even when it looked like I was a mess, and I was just interested in drugs, that was never really the case. I was always caring about other people, and trying to help, even when I couldn't help myself.”

There were still a few disconnects. I reached for ideas that didn’t quite land, or he shifted gears before I was ready. But the relational foundation was strong enough to hold it. I wasn’t trying to prove anything. I was just being myself—curious, tangential, and invested in meaning-making.

From Friction to Flow

Earlier this month, I wrote about preparing for the SQIP conference and how those early conversations with Michael factored into the development of my method. Relational–developmental autoethnography wasn’t something I could name in 2017, but I was already practicing it. I was using dialogue to make meaning, writing to integrate experience, and returning again and again to my inner and outer reflections. That’s what RDA is—it’s a way of living inside the questions, especially when they’re shared. And this connection with Michael helped shape that.

Looking back now, I can see that so much of what defines my work today was already taking shape in those early conversations. My questions about misdiagnosis, the moral weight of self-authorship, and honoring emotional and developmental complexity weren’t fully formed, but they were alive and stirring beneath the surface.

Today, I’m still following those threads in my writing and podcasting. I’m creating spaces where people can see themselves clearly and feel less alone in their inner conflict. I no longer feel the pressure to explain everything or to justify my place in the conversation.

Those early conversations with Michael weren’t polished, but they marked a beginning. They pulled something forward in me that had been waiting to emerge. I didn’t know then what I was stepping into. Reading the transcripts now, I can see the line that runs from that first spark to everything I’ve built since. And I’m still becoming.

Chris: This is superb. Resonant and beautiful. Thank your for sharing the steps of your journey. It speaks to me. Thank you.

I'm looking forward to more stories about your deep engagement with the theory.