From the Archive: Inner Growth

Unilevel and Multilevel Development According to Dabrowski's Theory

Welcome to the first official “From the Archive” post. We’ve added DC Archive to our navbar, where you’ll find posts like this one with media shared from our Dabrowski Center archive.

The presentation featured in this post was given by Dr. Michael M. Piechowski at the 12th Annual Hollingworth Conference for Highly Gifted in Manchester, New Hampshire, in May 1999.

Click below to download the original handout that accompanied this talk.

This audio recording was converted to mp3 from a cassette tape Michael sent to Chris in June 2018. The handout was discovered in a box of transparencies and documents Michael shared with Chris in May 2021.

For those who are new here, Michael joined us on Episode 48 of the podcast. Click here for more posts and episodes mentioning Michael.

The transcript has been edited for readability. Thank you, Michael, for your help!

When I met him [Dąbrowski], we had interesting encounters, and we started working together because when he gave me some of his writings to read, those that were translated into English, the people who translated them didn’t understand what he was talking about, and he didn’t always express himself clearly.

I said, “Well, you know, what you have here is all scrambled.”

So, he said, “Let’s get down to work.”

That’s how we started working—writing out what he wanted to say and expanding and elaborating.

This work went on for several years, and then he started his research project that was funded in Canada to find case material illustrating the levels in his theory and how to assess them. When I left the University of Alberta, I went back to graduate school to get a degree in counseling, and my first job after that was at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

I was teaching a course on personality for majors in education and related fields, and I used Maslow—his Farther Reaches of Human Nature. To place you in time, the three people who are closely related in ideology are Assagioli, he is the one who’s known for psychosynthesis. He was born in 1888. And then, Dąbrowski was born in 1902, and Maslow was born in 1908, to whom we owe the hierarchy of needs and the concept of self-actualizing people.

Self-actualization is a concept that is totally misunderstood by most people because people think, “Well, self-actualization means I am seeking my own fulfillment,” and they don’t read what he said about it.

What he said about self-actualizing people is that they are very conscious of doing work that is useful to others and humanity. They are kind to people, democratic in their spirit, and so on and so forth. There is nothing self-serving or absorbing or seeking just your own fulfillment. The fulfillment is in a very expanded, larger frame.

So, there was this affinity, and I did some work on that, which was on Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. He was part of the study as a representative of a very high level of development.

When I read Maslow's description of self-actualizing people for the first time, I said, well, that fits everything we have done with Saint-Exupéry. You know who Saint-Exupéry was—the author of The Little Prince. And the other ones are Vol de Nuit, Night Flight, Wind, Sand, and Stars, and things like that. So that’s how it all started, and then the question was, there was autobiographical material collected to illustrate the levels, but really, the processes that Dąbrowski from the start was stressing were the growth process, which he called unilevel and multilevel.

Here, I give you the outline of his levels, just to remind you that he talked about primary integration when there is not much inner life and inner psychology in a person. That things can disintegrate inside the person. He was most interested in the types of inner restructuring, the inner disintegration that goes on, so that’s what I want to illustrate today.

The first one, which he called unilevel, is when things are pretty fluid and discombobulated, and there is a lack of sense of direction. Then, the sense of direction emerges, which he called the split between the higher and lower in oneself, and the reason he called it that was because this is how people talk about it, when they experience it when it starts.

Then it goes toward the process—the inner process goes to a greater unity of the self, which then is lived in as universal values, and then he called it secondary integration. So the description of levels you have in the handout, I don’t want to go into the details of it, I would rather go into the examples. Another way of looking at his conceptions of levels is that the level one is really living on the surface of life. Just in the concrete things of everyday life. The concrete things of amassing material possessions, or status, or things like that.

And then when things go deeper, more emotional, more fragmented, we get level II. We get to more depth, to the self of the person, the true self, in III. And then IV and V, we get deeper and deeper inner and universal realities. So, that’s another way of looking at it: that through the levels, we reach greater depth—psychological and spiritual depth.

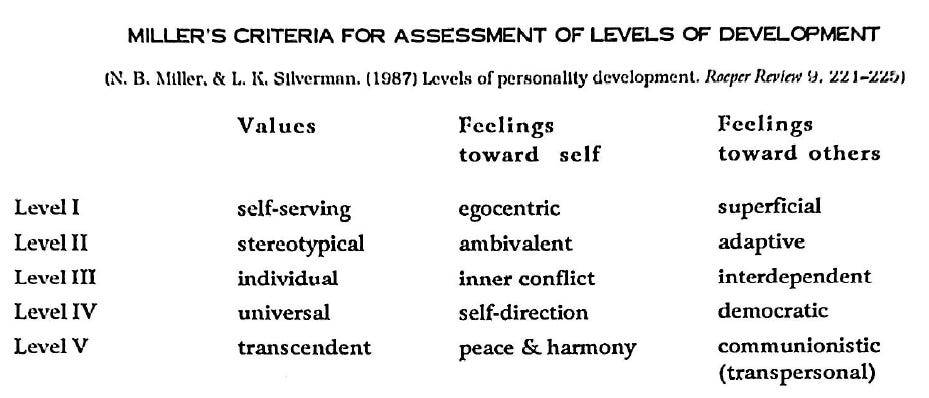

Another way to get a quick handle on the levels is the system of assessment that Nancy Miller developed in her dissertation at the University of Denver many years ago. We always had so much trouble getting responses from people and trying to do research, assess the levels, and things like that.

Reading someone’s response—well, is it a II and a half, is it III, is it II, is it I and a half? People who knew the theory very well were fairly close, but still, there was a fair amount of wobble in the assessments.

[In Nancy Miller’s coding system, one assesses feelings toward self, feelings toward others, and values.]

Thinking through what his conception of the levels was about and what it really describes, we didn’t have to assign numbers. We just found if, in the response to the questions that we asked, whether the values of the person were self-serving—what’s in it for me? Whatever I do, how am I affected? Self-serving. Whether the feelings toward the person were egocentric toward oneself. Always “me first”—that’s much easier to gauge. Whether feelings toward others were superficial. Whether there was no emotional depth or true attachment.

When you look at these things, the level is easier to figure out. In [level] II, the values are the mainstream values, stereotypical values, and common. Feelings toward self fluctuate; they’re ambivalent, and we’ll talk more about that. Feelings toward others are adaptive. By adaptive, she means there is much that is done to please others and to look good. We’ll have examples of that.

When we get into what he called the multilevel process [level III], we have this vertical split between higher and lower within oneself. The present state of affairs is something that needs to be changed. And Dąbrowski used to refer to it as ‘what is,’ but then there’s a sense of ‘what ought to be.’

Realizing one’s potential of becoming a better person, better human being. So, the values become individual because we see others as individuals also. And there is a lot of inner conflict. OK, where I am now, I want to get away from, but it’s not always such an easy thing.

So, that’s where the inner conflict is. And the feelings toward others are the recognition of interdependence, connectedness, and so on and so forth.

Then, when we get to level IV, which he described, the values become universal.

When I did a study of Eleanor Roosevelt, that came out very strongly. The same as in Saint-Exupéry. They had actually a lot in common. As persons, they were totally different. He was very spontaneous, adventurous, and a writer, and things like that. But he was a very loyal friend.

Eleanor Roosevelt was much more organized. She worked very hard and was full of compassion for others. People said she still was part of the Victorian era of being proper. But really, she was not—it wasn’t about proper; she had a great sense of decency, I would say.

The self-direction, the democratic feelings, consideration for other people, they have shared that in common, and when you look at their values and how they express them, you can see great similarity, which is exciting. They are totally different people, and that’s what’s exciting when you find these people at a very high level of development, that as individuals, they are very, very different, yet when it comes to the core of values, what they believe in, and what they operate on, it’s very similar. That’s why ‘universal’ makes sense.

So, finally what he called the secondary integration, the values are transcendent. The feelings toward self, there is a sense of peace and harmony. Nancy Miller called the feelings toward others communionistic—a sense of commonality—and since we have transpersonal psychology, I think we can call it transpersonal feelings. The sense that we are all connected.

Peace Pilgrim said, once you get to the higher level, you can see how we are all connected. This outline makes it much easier to handle because if I showed you all the levels in detail, we would be here for days.

The primary distinction that Dąbrowski made was between the unilevel growth process and multilevel growth processes. When I came across Fritz Perls’s Gestalt prayer, I said, this is the essence of what unilevel means:

I do my thing and you do your thing.

I’m not in this world to live up to your expectations.

And you are not in this world to live up to mine.

And you are you, and I am I,

and if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful.

If not, it can’t be helped.

So, there is the recognition that everyone has the right to go his or her own way. But if you see the last line, “if by chance we find each other, it’s beautiful, if not, it can’t be helped”—you can’t build relationships on that. Because the relationship would be just a series of chance encounters. There would be no continuity.

This expresses much of that fluctuation, changes of direction, changes of feelings, being much governed by mood and the moment, and that there’s no sense of the inner core of something.

However, growth does proceed, and you have in the handout the expression of this inner state in adolescence. It’s very characteristic of adolescents to go through this kind of disintegration, being subject to the influences of others and peers.

If you know Mary Pipher’s Reviving Ophelia, she has many examples of highly gifted girls, highly intelligent, who prior to going to junior high school were very confident in what they were doing, very interested. They enter this chaos and these pressures, and all of a sudden, it’s all important to them how the boys look upon them. Whether they look good.

There, she makes the difference between those girls who go through this process and can come out of it and be themselves again and those who need a major rescue operation: counseling, psychotherapy, and things like that. She describes it extremely well.

Here, to give you the expression of it, is this student I had in my Personality Theories class. When we talked about achieving a sense of identity, this is what he wrote about his quest for occupational identity:

He says he has suffered confusion “Because of my confusion as to what I want to become,”—he had trouble establishing his identity—“I have many interests, but I am at a point where I don’t know which one to follow, which I really like the most. I am indecisive and lack the knowledge of what I really like and want to become. It disturbs me because I wonder when I will know, or if I’ll jump into a field that I later will be disappointed with. I feel also that I must be going nowhere and I am as if I have no direction.”

That’s characteristic of unilevel process, and in his second answer, to “Have you established a satisfying occupational identity?” He said,

“No, I have not, and when I do I’ll let you know. I am juggling many ideas in the air, always tend to change my mind. Perhaps nothing appeals to me or perhaps I think it should be easy to jump into something. Or even perhaps I have no patience.”

So, there is this lack of any inner core. Now, this can change. There is a wonderful study based on interviews with about, over 140 different women—young, teenagers, up to older ages. In Women’s Ways of Knowing by this terrific team of Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule, that was published in 1986. There is a 10-year anniversary edition that came out in 1996, with a wonderful forward on how they were working together. And there, I found the best expression of the unilevel growth process.1

It so often happens that people come across Dąbrowski’s theory, learn about the levels, and then put people into levels. They say—this is a level I person, this is a level II person. Please, don’t do that. This is just a theory to give us a handle on some things, but not to categorize people.

There is a tendency to look down upon this level II stuff. This shouldn’t be because, as you will see here, they describe that what they were looking at was the women’s sense of self and how they view knowing—their own knowing or knowledge that comes from elsewhere. They found out that there is a developmental direction. They found many women depend—just as students depend—on external authority for their knowledge, and they don’t use their own judgment.

If you are a teacher, you find out that there are some people who, because they are so unsure of themselves, have to copy what others have said. They cannot even paraphrase it in their own words because they don’t have this kind of assurance.

These women were emerging from the reliance and complete faith in the authority of others, which usually is the male authority. Then, they turn into themselves and depend on their inner feeling. So, it’s a very tender time that they have to protect, at that time, when they are beginning to rely on their own feeling, and then they cannot take much from the outside because it would, you know, kind of threaten and interfere with it, so it’s very much to be respected.

You have the introduction here:

“I can only know with my gut, I’ve got it tuned to a point where I think and feel all at the same time, and I know what is right. My gut is my best friend, the one thing in the world that won’t let me down, or lie to me, or back away from me.”

The step in this direction is because the authority she relied on breaks down. They find betrayal, they find—there are some very dramatic cases.

For instance, some of the women found out that the men that they relied on were engaged in some incestual relationship or sexual abuse or something like that. They said, well, I cannot respect this authority anymore. It’s a crisis. This is the movement to relying on her own feelings.

Here is another woman who said:

“It’s like a certain feeling that you have inside you. It’s like someone could say something to you and you have a feeling. I don’t know if it’s like a jerk or something inside you, it’s hard to explain.”

Now, it’s very interesting she mentioned that there might be a jerk inside. A process developed by Eugene Gendlin, who worked with Carl Rogers for many years, to get hold of what works in counseling. He devised a process of focusing, and in this process of focusing, when the thing that we are trying to get hold of—what is unclear and dark, or unknown, but it’s wanting to come out. When some way of expressing it, whether a phrase or an image, comes in, and we suddenly know what that is all about, there is an inner shift. And in some people, this inner shift is a physical jerk. There is a real physical change in feeling.

So I take it that, in her, when this process operates, this is what she refers to, it seems to me. What that often requires is walking away from the past, and there is example here that’s rather dramatic:

“Being married to him was like having another kid. I was his emotional support system. After I had my son, my maternal instincts were coming out of my ears. They were filled up to here. I remember the first thing I did was to let all my plants die. I couldn’t take care of another living damn thing. [Laughter from audience.] I couldn’t… I didn’t want to water them, I didn’t want to feed anybody. Then I got rid of my dog.” [More laughter.]

Now, this raises an interesting question. If you studied Alfred Adler and know about him, his cure for neurosis was to do something for others. But there has to be a balance. If, like this woman, like many other women, just to serve and serve and serve, and nothing comes back, a crisis arises.

My mother, I remember, said one day that she was thinking of what someone else did—to put hay on our plates. Because we never told her how good her meals were. She said, well then, maybe that will wake you up. And she was right—she should have done it.

The quest for self begins, and there are a few expressions. I won’t read all of them. But some are very telling:

“I always thought there were rules, and if you followed the rules, you would be happy. And I never understood why I wasn’t. I would get to thinking, gee, I am good, I follow the rules, I do everything they tell me to, and things don’t go right for me. My life was a mess. I wrote to a priest that I was very fond of, and I asked him, what do I do to make things right? He had no answers. This time, it dawned on me that I was not going to get the answers from anybody. I would have to find them myself.”

When you read further down, you’ll find out that the experiences of living moment to moment, respecting the inner feeling but not knowing what I am going to be in the next moment or the next day, move to the sense of being very young. The growth begins.

There are the images of being very young, for instance:

“The person I see myself as now if just an infant. I see myself as beginning. Whoever I can become, that’s a wide-open possibility.”

When you see this, you realize that the tremendous growth process, tremendous change that’s undergoing in a person, even though it’s a unilevel process still, it hasn’t reached the vertical direction that we’ll get to. But it’s a very, very important process. And another one said:

“I actually think that the person I am now is only about 3 to 4 years old, with all these new experiences.”

These new experiences of finally trying to get your own voice when there was no voice before.

“I always was kind of led, told what to do, never really thought much about myself. Now I feel like I am learning all over again.”

This is about the process of becoming your own person. Respecting yourself, who you are. That fits well in what Dąbrowski called the unilevel process.

Then, we can see the transition from unilevel to multilevel. This was written by a boy of 16, and I lost the source where I got it. I hope one day I’ll find where I got it from. But he said it so beautifully. He said:

“I am myself, although I know not which self that is. For I am many identities trapped within one reality. I am the eagle, for my imagination soars above the earth. I am the lamb, timid and shy. And yet I am also the lion, the king of my world. And when I roar, all my selves must obey. I cannot say which is the true me, or if there is truly me at all, so I persevere. I search and seek and hope to find my self. The one island amidst a sea of swirling identities.”

So, you have this multiplicity. Many selves, and not knowing which one is the true one. Which one do I belong to. But there is a sense of searching, and then he says:

“Come, help me in my quest, for you are as much me as I am you. And both of us together can never be one, the world can never be one, while I am so many.”

This is the search for inner integration, the search for the emerging direction for this person. And that, in my mind, expresses the transition from the unilevel to multilevel process.

Now, the richest material I have found so far of the inner growth process, which Dąbrowski described as multilevel, is in the diaries of Etty Hillesum. Some of you probably know who she was. She was a young woman in Holland during the time of the Holocaust, [she lived from] 1914-1943. She studied Russian, she was giving lessons in Russian, studied Russian literature and philosophy, she was very bright.

She was a pretty happy person until something happened inside her. That’s what Dąbrowski called a spontaneous multilevel disintegration—the spontaneous process of change. Something shifts inside and demands a new direction, a new digging in. That’s what she said at the very beginning of her diary:

“So many inhibitions, so much fear of letting go, of allowing things to pour out of me, and yet that is what I must do if I am ever to give my life a reasonable and satisfactory purpose. I am accomplished in bed, just about seasoned enough I should think to be counted among the better lovers.

And love does indeed suit me to perfection, and yet it remains a mere trifle, set apart from what is truly essential, and deep inside me something is still locked away. I seem to be a match for most life’s problems, and yet deep down something like a tightly wound ball of twine binds me relentlessly, and at times I am nothing more or less than a miserable, frightened creature. Despite the clarity with which I can express myself.”

She describes this inner condition, this inner chaos—that the forces were “at loggerheads” within her. She suffered from depression and inner—I wrote here “inner obstruction”—she called it inner, spiritual constipation that she was suffering from. These are her own words. There is the expression of that spontaneous process of something new demanding to be attended to.

“I long for something and I don’t know what it is. Inside I am totally at a loss, restless, driven, and my head feels close to bursting again.”

Very intense process.

“And this morning, everything is fine again, but later it was back, all the questioning, the discontent, the feeling that everything is empty of meaning. The sense that life was unfulfilled. All that pointless brooding. And right now I am sunk in the mire and even the certain knowledge that this too shall pass has brought me no peace this time.”

Now when she talks about the pointless brooding, that everything is empty of meaning and so on. Perhaps you are familiar with William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience, where he describes the once-born and the twice-born.

The once-born are the people who can live their religion and their faith, and they don’t have the crisis of doubt and the internal brooding and going through this whole awful process of not knowing. Of this discontent and things like that. But the twice-born are the ones who go through this questioning process and doubt, and that’s a growth process.

She gets to work on herself, and she actually developed a way of meditating. She also sought out the help of a counselor, who was an interesting guy because he was very intuitive.

When he met Carl Gustav Jung, Jung told him that he should develop his technique of intuitive reading by holding a person’s hand. So, he was called a chiropsychologist. Which is different from a palm reader. But if you want more details, read the diary because there are some interesting things—how he wrestled with his clients to awaken them.

Anyway, she said,

“I must work on myself more, there’s nothing else for it. A few months ago I did not need all this effort, life was so clear and bright inside me, and so intense.”

See? “A few months ago I did not need all this effort.” Something happens inside the person. It’s not an outside trigger. It happens on its own inner clock.

“But now everything has ground to a halt except for a bit of agitation, but it’s not real agitation, I’m too depressed for that.”

She undertakes the struggle, and this is how she describes her inner struggles.

“I’ve become just a little stronger. I can fight things with myself.”

This is what Dąbrowski described as inner conflict: I can fight things with myself.

“I had the desperate feeling that I was tied to him and that because of that I was in for an utterly miserable time.”

That should sound familiar to some people. [Laughter.]

“But I pulled myself out of it, although I don’t know quite how.”

She says, “I don’t know quite how,” and then she says how she did it.

“Not by arguing on myself but by tugging with all my mental strength at some imaginary rope. I threw all my weight behind it and stood my ground, and suddenly I felt that I was free again. And the lesson learned is this: thought doesn’t help. Thought is just introspection, intellectualizing, figuring things out.” But, she says, “What you need is not causal explanations, which you get in psychoanalysis, but will and a great deal of mental energy.”

The will to change. The will to become free of what’s binding us. And then she says,

“It’s a slow and painful process, this striving after true inner freedom. Growing more and more certain that there is no help or assurance or refuge in others. That the others are just as uncertain and helpless and weak as you are. You are always thrown back to your own resources, there is nothing else.”

Through this process, she grows gradually more and more, finding her inner core. She is getting more and more in touch with her true self. There are so many beautiful expressions; I’m only using those to illustrate the process that she is going through. But, for instance, what I’m not including here is the intense life of prayer that she developed.

When in the beginning, she said, “I should be counted among the better lovers,” later on, she said the only love letters one should write are love letters to God.

She looks upon the first year of her diary and the process of counseling she was undergoing, and she sees progress:

“This year has meant greater awareness and hence easier access to my inner resources. And I listen into myself and allow myself not to be led not by anything on the outside, but what wells up from within. It’s still no more than a beginning, I know, but it’s no longer a shaky beginning. It has already taken root.”

She later gives images of how even though she feels inner storms, there is that post—with a good foundation, amidst all these storms. Her inner growth process moves her to an expansion of her consciousness. To awareness of others, of the struggle of others, and the connectedness with others. For instance, when she says,

“The rottenness of others is in us, too. I see no other solution than to turn inwards and root out all the rottenness there. I no longer believe that we can change anything in the world until we have first changed ourselves.”

It is interesting that Eleanor Roosevelt said the same thing—we have to change ourselves if we want to change the world. That’s not what they teach us in school.

And she said, “That seems to me the only lesson to be learned from this war.”

Now, the war was raging in Holland, and she was Jewish. And the Jewish people were being gradually more and more limited, they couldn’t take public transportation, and they were limited to certain stores, and they were gradually picked up and shipped to concentration camps.

There was a transit camp in Holland, Westerbork, and she volunteered for that camp. Because some people tried to help her escape from Holland to England or somewhere. She refused to do that. And they found her a job with the Jewish Council, which protected her for some time, and she had misgivings about it. So that’s why she volunteered for the camp that people were in. For a while she had a pass, she could go in and go out, and was helping people. But after a while, she became a regular intern like everyone else. Those who remember her—who survived—said that they remember that her personality was luminous.

She mentioned other people who were also very helpful to others, and there was tremendous crowding. When the weather was dry, the sand and dust were blown up by the wind, so when they could, they asked people on the outside to send them goggles because it was so extremely bothersome. And when it was wet, they were just walking in mud. But then, every Monday, they were put on the cattle cars going on to Auschwitz and other concentration camps. So that’s where she ended up, in Auschwitz, and her parents and also her brother. [38:26]

What she struggled with was to root out her feelings of hatred for the Nazis. And she succeeded. For many people, the problem is, they say, well, things like that cannot be forgiven. And yet she was able to overcome that, so these are difficult things. But that’s what she has achieved here. She says:

“Each of us must turn inwards and destroy in himself all that he thinks he ought to destroy in others. Every atom of hate we add to this world makes it still more inhospitable.” And that applies to our everyday life. “Ultimately we have just one moral duty, to reclaim large areas of peace in ourselves. More and more peace, and reflect it toward others. And the more peace there is in us, the more peace there will be in our troubled world.”

And then she reflected on the war. She says,

“Why is there war? Perhaps because now and then, I might be inclined to snap at my neighbor. Because I and my neighbor do not have enough love. Yet we could fight war by releasing each day the love which is shackled inside us and giving it a chance to live.”

And how tremendously apropos that is for what is going on currently. You know, since I lived through World War II, when I think of the situation in Yugoslavia, I said, this is the greatest shock. This is a replay of World War II on a smaller scale, but the cruelties are the same. What’s going on is the same. It’s no different from the Holocaust. I cannot understand why Kissinger was able to say that Milosevic is not Hitler. Not like Hitler. Well, he is. What he’s doing is. So, we have it. We do have it.

Well, I’ll quote to you the one thing from the earlier part of the diary when she was struggling with the hatred. That’s where she was feeling in an earlier time:

“The whole nation might be destroyed root and branch”—that’s when she was thinking about the Germans—“and now and then I say nastily, they are all scum, and at the same time I feel terribly ashamed and deeply unhappy. But can’t stop even though I know it’s all wrong.”

That’s our natural impulse. To strike back. So that was, you see, page 11 was very early. There is a new edition of the diary. It’s absolutely an amazing document because when I first came across it, I started taking notes. And I write very small, so I was able to take notes on one page from 10 pages. When I was at 100 pages, I had ten pages of notes. I said, well, eventually, it will slow down. Well, I ended up to the very end writing things at the same rate because she comes up with new and profound things all the time. There is no repetition.

That’s Etty Hillesum. Now we go on to Peace Pilgrim. She was born in 1908, and for a long time no one knew what her real name was, or her first name was—she was Mildred Norman. She grew up on a farm. There’s a beautiful documentary available now, and some of her talks have been videotaped. She died in 81.

From a young age, she was recognized as having certain authority about her. And leadership. She was very vivacious. She was also very sportive, she liked to go to the river several miles away and jump from the bridge into the river. Things like that.

So then, she became engaged and married, but by that time, she was already a pacifist. When her husband was called to military duty at the beginning of World War II, she told him she was not going to see him where he was as long as he was in the army. He felt, well, she’s not being a good wife. So, he asked for a divorce. He said, I wanted a homemaker, and she certainly wasn’t a homemaker. Then he said, well, then she was free to pursue her path.

When she took up the pilgrimage for peace in 1953, she said she would walk for peace 25,000 miles. And she was very careful about counting the miles. If someone gave her a ride, which happened, for instance, the police picked her up for vagrancy, and she would spend the night in jail, she asked them to bring her back to the exact spot where they picked her up so her counting wouldn’t be messed up.

Only the first 45 minutes of the recording were available. The rest is missing in audio, but you can find it in the handout.

Michael later published a paper with their study as one of his examples of unilevel development.