Who is Michael M. Piechowski?

A glimpse into why we mention this man so often on the podcast and in our posts

If you’ve been listening to the Positive Disintegration Podcast or reading our posts with Interesting Quotes, you may have noticed that I often mention Dr. Michael M. Piechowski, and I sometimes use only his first name on the pod. This is partly because he’s well-known in the field of gifted education—he’s written so much about Dąbrowski’s theory that many people already know his name.

But it’s mostly because he’s my friend, mentor, and an important person in my life. In this post, I will say more about Michael so listeners and readers unfamiliar with him will understand why he comes up so often in my work.

Michael worked with Dr. Dąbrowski for eight years after they met in early 1967 at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. He has written extensively about the theory of positive disintegration and is responsible for introducing the overexcitabilities to gifted education in 1979.1

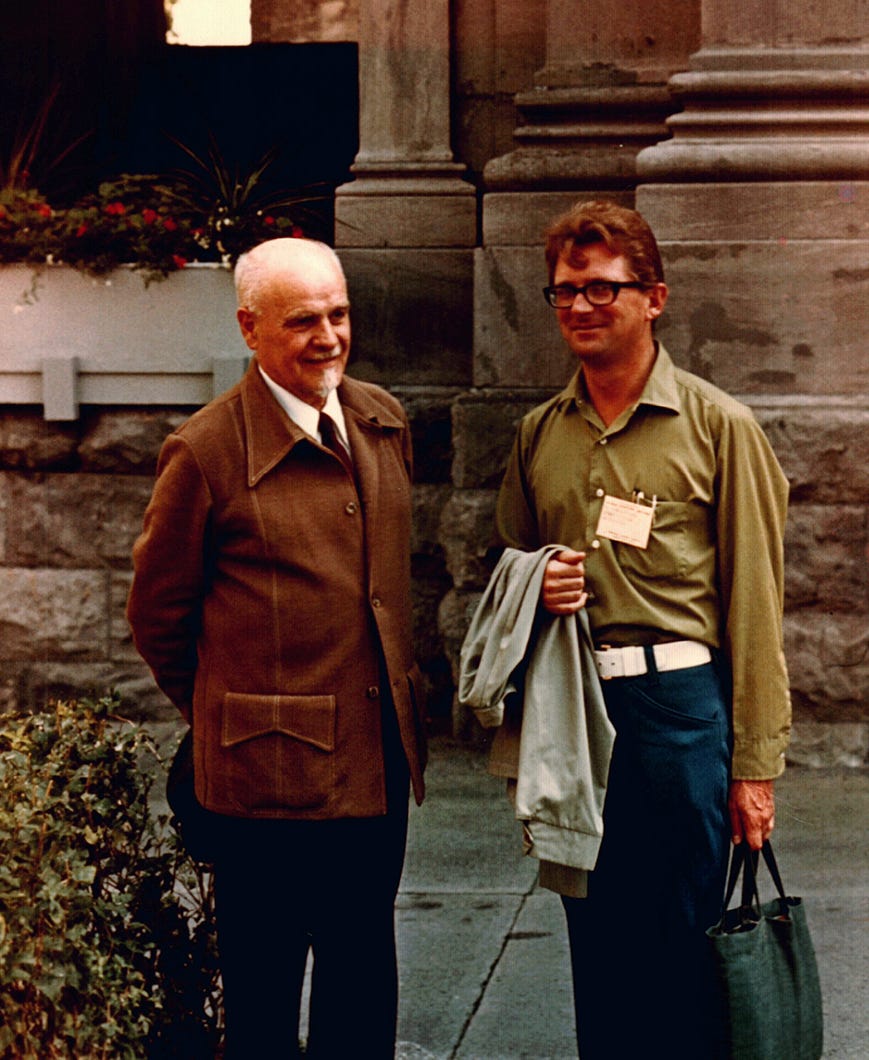

Here’s a photo of Dąbrowski and Michael that I used in my first presentation at the National Association for Gifted Children conference in 2017. My session title was “Honoring Dąbrowski’s Mission: Piechowski’s Contribution to the Theory of Positive Disintegration.”

Intensity in Action

When I met Michael via email in 2016, it was thanks to his work as Associate Editor for Advanced Development Journal because I had submitted a paper to the journal based on my autoethnographic work.

I remember standing in my kitchen and receiving an email from Michael on my phone. At first, I was gobsmacked and wondered, “Why is he writing to me?” I realized he was sharing editorial feedback about my paper. It was the day before my 43rd birthday, and I was completely overwhelmed by his feedback. I was a doctoral student, and this was my first peer-reviewed paper. It took me two days to write back with thanks and to say I’d get to work on a revision.

The story I was trying to tell in the paper was my own, but it felt too big and unwieldy, and I struggled with where to even begin with the revision. Dr. Nancy Miller, editor of Advanced Development, suggested I ask Michael for help. That felt so daunting.

At that time, I’ll admit I had only skimmed the surface of Michael’s work. I’d read his chapter in the second edition of the Handbook of Gifted Education2, Living with Intensity, and I’d purchased his book Mellow Out after attending a workshop on coding the open-ended Overexcitability Questionnaire several months earlier. But I hadn’t actually read his book yet, and sharing my thoughts and questions felt impossible. He seemed so intimidating. And, for some reason, I didn’t expect him to be kind.

One month later, I wrote to him again:

For the past few weeks, I have been thinking about how to approach revising the article you reviewed... Nancy suggested that I write to you directly about the struggles I'm experiencing, and while I know she is right, it feels very odd to ask for your help. But I know she's correct—that you can help me make sense of this unwieldy story—because your observations and questions were so spot-on. (Email to Michael, April 29, 2016)

Now, when I go back and read our early emails, I know him well enough to hear his voice in my head while reading his words. But at the time, I didn’t know him, and he didn’t say much. Still, I didn’t let that stop me, and I shared my thoughts and asked my questions.

For the first year of knowing Michael, all of our contacts were via email. By June 2016, I decided I wanted to read everything he’d written.

I began with Living with Intensity and Michael’s monograph from 1975 titled “A Theoretical and Empirical Approach to the Study of Development,” which starts with a foreword from Dąbrowski. Next, I read his chapter “Discovering Dąbrowski’s Theory” and finally dived into reading Mellow Out, a book that had a more profound impact on me than nearly anything else I’ve ever read.

Here are some of the readings I did that summer in case you’d like to check them out for yourself.

Books

Mellow Out by Michael M. Piechowski

Living with Intensity by Susan Daniels and Michael M. Piechowski (Editors)

Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration by Sal Mendaglio (Editor)

Articles, chapters, etc.

Dąbrowski’s foreword from Piechowski (1975): A Theoretical and Empirical Approach to the Study of Development

Piechowski (1978): Self-Actualization as a Developmental Structure: A Profile of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Piechowski (1979): Developmental Potential

Piechowski (1986): The Concept of Developmental Potential

Piechowski (1992): Giftedness for All Seasons

Piechowski (1993): Is Inner Transformation a Creative Process?

Piechowski (1997): Emotional Giftedness: The Measure of Intrapersonal Intelligence

Piechowski (1998): The Self Victorious

Piechowski (2002): Experiencing in a Higher Key

Piechowski (2008): Discovering Dabrowski’s Theory

Jackson, Moyle, & Piechowski (2009): Emotional Life and Psychotherapy of the Gifted in Light of Dabrowski’s Theory

Piechowski (2014): Rethinking Dabrowski’s Theory: I. The Case Against Primary Integration

I also read his papers about the exemplars:

Eleanor Roosevelt (1990)

Etty Hillesum (1992)

Peace Pilgrim (2009)

There are more documents I could share, but I don’t want to overwhelm you.

I have hundreds of pages of handwritten notes from the reading I did in 2016 when I spent the summer and fall immersed in Michael’s work. I set the intention to read everything he’d ever written for the public, and it took time to make that a reality.

With his help, I revised my paper, which took a different direction thanks to everything I was reading. In the paper, you’ll note that I didn’t cite anything from Dąbrowski and wrote only from what I’d learned based on Michael’s work. This is because I only cite publications that I’ve actually read, and I had not made it far in KD’s work as of August 2016.

In retrospect, I can easily say that I would have walked away from the theory of positive disintegration if Michael’s interpretation of the theory hadn’t captured my interest and enthusiasm the way it did.

Who is Michael as a person?

You can see that Michael is a scholar, and he’s been working with the theory for many years. But who is he beyond his work? It took much longer to figure that out. As I was reading his work, I wrote long email messages to him with thoughts, questions, and examples from my personal data.

I looked in the literature for clues about him, and his book Mellow Out had some insights.

Earlier in my life I was first a plant biologist and then a molecular biologist. As a molecular biologist, I studied the maturation process of a bacterial virus. What interested me above all was life at its most fundamental level—the workings of the living cell. Such marvels. Within its tiny walls: the cytoplasm streaming around in a continuous movement, the nucleus loaded with heredity and looking like a potato with an eye, the mitochondria—little delicately built floating factories—and the chloroplasts, which trap sun rays, resplendent in their exquisite architecture and pigmentation. Almost all life on Earth depends on them. Exploring these wonders is immensely satisfying—there is no end to new puzzles and new discoveries. (Piechowski, 2014, p. 17)

Michael has two PhDs—first in molecular biology in 1965 and second in counseling and guidance in 1975, both from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. I was interested in his decision to leave science to study psychology and giftedness.

With my Ph.D. in hand, I took a faculty position at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Alberta. During the first year I began to be haunted by the image that I was walking down a hallway. At the end was a wall with glass blocks to let in the light, but there was no exit. This recurring image was showing me a block in my life's trajectory. I knew then that I had no future in science. I had to change fields.

Shortly after I arrived at the University of Alberta in January of 1967, I met Kazimierz Dabrowski, a Polish psychiatrist and psychologist who held both M.D. and Ph.D. degrees. He was the author of a theory of emotional development that he called, paradoxically, the theory of positive disintegration. I had previously heard about it from an Italian friend of mine who had asked me: “Do you know that Polish psychologist who says that neurosis is not an illness?” I was a biology student back in Poland and didn't know any psychologists then. When I met Dabrowski I asked him if he was the author of that theory. Of course he was. By curious synchronicity he looked at personality development as emotional development. This was exactly where my change of heart was moving me to. (Piechowski, 2014, p. 17).

Since I live in Colorado, I’d had the opportunity to meet some of Michael’s friends who lived here, such as Nancy, as mentioned above, and her husband, Dr. Frank Falk. At that point, I’d also had a few conversations with Dr. Linda Silverman, and everyone spoke about Michael with deep respect that bordered on reverence. I couldn’t wait to meet him in person.

Scouring the Internet for any sign of Michael and his work, I found a brief interview he’d done in 2009 on Wisconsin Public Radio3. In 2016, I was still smoking cigarettes, and many nights that summer, I’d listen to the recording with earbuds on my phone while I was outside on the porch. The things he said described my life, and while I didn’t realize it then, I was bringing Michael and his voice into my head. (I’ll say more about this in future posts.)

I would write to Michael with thoughts from the work I was doing alongside my reading. I continued my autoethnographic process of coding and interpreting my writing from the past. Sometimes, he would send me a message and point me to places in Dąbrowski’s work. I’d managed to get a print copy of Dąbrowski’s 1967 Personality-Shaping through Positive Disintegration and was able to look up this reference from him in July 2016:

Chris, when you are describing your epiphany, I am inclined to think that the turning point came as a result of what Dąbrowski called “prise de conscience de soi même”—a sudden profound moment of self-awareness (Dąbrowski, “Personality-shaping through positive disintegration”, 1967, p. 104):

“an act of a sudden understanding of the sense, causes, and purposes of one’s own behavior.”4

From repeated acts like this grows the dynamism of subject-object in oneself, he says.

Positive maladjustment involves a social situation, an objection to what others are doing that is wrong. (Email from Michael, July 19, 2016)

It’s hard to capture the way that I spent every free moment that summer learning the theory, revising my paper, and getting to know Michael.

As soon as I started writing more than a couple of emails per month, I intuitively knew that I should save our messages for easy reference. It helped me keep track of what I’d told him, as well as the things he was sharing with me. I began collecting the messages in QDA Miner and keeping track of the stats in a spreadsheet.

Seven years later, I still diligently save all of our emails, and at the end of each month, I tally how many messages we’ve sent to each other and our word counts. I considered sharing those stats here, but that should be a whole separate post because the numbers are enormous.

Michael was kind with me even though I was overwhelming him with words. I remember having a conversation with Nancy because I was worried that it was too much for him, and yet, I didn’t know how to stop. She told me that he had ways of handling it, and that was true. He has strong boundaries, and for the first several months, he would let my messages accumulate until he was ready to deal with them.

A Vision of the Future

I’ll admit that during the first few years of getting to know Michael, I worried that I wouldn’t have enough time with him. He turned 83 in 2016, and I worried about his age. Could he be the mentor I’d been searching for? Was he even interested in doing such a thing? These things kept me up at night and were the source of suffering for some time.

I would have vague images in my mind of working with Michael, but I didn’t know when or where it would become a reality.

By the end of 2016, I’d figured out a direction forward for my first official project with the theory of positive disintegration. I decided to undertake a comprehensive review of the literature from Dąbrowski and Piechowski for NAGC 2017. I’d already read Michael’s work at that point, and I was absorbed in the process of taking in all of Dąbrowski’s English works.

During the winter of 2017, I began bugging Michael to let me visit him in Madison, Wisconsin. I met him in person precisely one year after receiving the first email message. On my 44th birthday, I flew home to Colorado and had what I now realize was a mystical experience at the airport and on the plane.

I’ve never met anyone like Michael. It’s going to take many posts, podcast episodes, papers, and probably multiple books before I feel I’ve adequately captured him and his work. This post is only the beginning.

In the first Interesting Quotes post I made this summer, I mentioned that my flight to Yunasa East had been canceled, allowing me to write that day.5 That night, I flew on a red-eye to Michigan and worked with Michael during his last Yunasa experience.

The camp started in 2002, and he has attended every single session since that time—I think he mentioned that there were 34 total camps for him because there were two per year for more than a decade.

I will wrap up this post with a photo of us together during the last evening, taken by a 10-year-old camper from my group.

As I said, this is only an introduction. I have enough to say about Michael to keep me busy for the rest of my life.

Note: After I published this post, Michael joined us for Episode 48, Piechowski’s Insights on Positive Disintegration.

The Dąbrowski Center hosts an archive of Michael’s work. You can watch my keynote address from the 2022 Dąbrowski Congress if you’d like to learn more about Michael and how our relationship developed.

See Interesting Quotes, Vol. 2 for Piechowski (1997) excerpts.

You can listen to the 2009 radio interview here. It’s from the WPR program, To The Best of Our Knowledge.

Here’s the whole paragraph from Personality-Shaping: “As the psychic development of an individual in the process of positive disintegration deepens, the dynamism in question begins to take shape and mature gradually and increasingly. However, besides such gradual nascency and maturation, it may manifest itself suddenly, unprepared, or rather prepared unconsciously, in the form of a synthetic act, succinctly expressed in French: prise de conscience de soi-même. It is an act of illumination, as it were, an act of a sudden understanding of the sense, causes, and purposes of one’s own behavior. As a consequence of repeated acts of prise de conscience de soi-même arises the “subject-object” dynamism. It is, therefore, a permanent continuation of these acts and as a consequence of this continuation the division into subject and object becomes something stabilized, something enabling the individual to possess a permanent insight into himself, not by way of unforeseen, surprising flashes on the mind; but by conscious insight into himself.” (Dabrowski, 1967, p. 104)

I talked about Yunasa in podcast episode 36, and you can read more about it from the Institute for Educational Advancement’s website.

This was rich and abundant, a very worthwhile read, Chris. Thank you