Thoughts from Writing about Self-Stigma

Follow up from the Overcoming Self-Stigma Series

As soon as I started sharing my writing here on Substack, I knew I wanted to do the Overcoming Self-Stigma series (Parts 1, 2, and 3), but I had no idea how it would look. Trying to tell such a huge story concisely was difficult. It meant leaving out a ton of context, but I decided it had to be left out. I knew I could write posts like this one to fill in the gaps when necessary.

I’m happy to be sharing this work. I wish I could articulate how difficult it’s been for me to tell my story in a way that’s manageable for me, the reader, and my family and friends. I thought it would come first in another book, but it turned out that I needed to start writing here.

The more I wrote up our podcast show notes on Substack, the more I realized I could use this platform to share my writing. I love how flexible it is and changeable, and I can easily link things together. By contrast, writing a book explaining how I learned about the theory and got to know Michael felt overwhelming. It still feels overwhelming, but I know I’ll get there eventually.

I’m glad it occurred to me that I could write about these things little by little on Substack. Whenever I publish a post, I immediately see all the parts I had to leave out. For instance, in Overcoming Part 2, I wanted to explain that now, I realize part of what I took for mental illness was mirroring my father. He was killing himself, and I started trying to destroy myself, too. But once I’d written about the trauma of losing my father from alcohol, I knew that was a story for another day. It didn’t belong in the post about self-stigma.

I also wanted to say more about how I used drugs in my mind for years before I used them seriously in this reality. My imaginal process was so intense that it felt like I was living in two realities simultaneously. Trying to write about No Guarantees and how the book was a mix of truth and fiction is very complicated. So, I also put that on the back burner for now, as well as the discussion of how my imaginal process has changed over the past several years.

Searching for Answers

One of the big questions for me during the autoethnography was, “Why am I still alive when so many others have died?”

My story is an extreme example, and there were many highs and lows for me. In my 20s, I started using drugs heavily, and I would use multiple hard drugs—meth, heroin, cocaine, crack—in one evening, and sometimes with alcohol. I had no respect for life nor fear of death. For several years, I lived in a deeply self-destructive pattern.

I wondered, how am I still here?

These questions haunted me, and when I discovered autoethnography, I was thrilled to have a methodological framework for exploring the past.

I wondered what I’d find other than the obvious: I’m gifted, and my family was always willing to support me. I’m an only child and was an only grandchild on one side, which seems to have been an advantage in some ways and a liability in others.

How much did privilege factor into things?

In our latest podcast episode with Dr. Matt Zakreski, he talked about his privilege, and I appreciated both his awareness and willingness to discuss that issue.

When I lived briefly among the homeless in Las Vegas in 1999, I realized my White privilege clearly for the first time. It astonished me to see how differently I was treated by people in authority because I’m White. I stayed with an older Black man, and whenever we passed a police car in our neighborhood, they would hassle us. On foot or in a car, it didn’t matter—it was suspicious for me to be there with him.

They would separate us because they thought I was there with him to get drugs. Well, they weren’t wrong, but the surprise was that I was living in the neighborhood and knew him.

I would talk back to the cops while this man I’d been stopped with nearly shook with fear. It was shocking to see how concerned he was, and he’d get angry with me for being belligerent with the police. Let me tell you, if I didn’t have drugs on me, I was angry for being stopped for no reason other than race. I was not going to take it quietly. He explained to me that we lived in different realities, and he had to fear the police in a way I didn’t.

It Takes a Village1

Here’s another example of my privilege. My mother would come down to where I was staying and drive me to the grocery store to get food. The neighborhood was a food desert, although I didn’t know that term at the time. We had only overpriced and limited convenience stores nearby, so this was a kind favor from her. She would buy me the things I needed but wouldn’t give me money because she knew I would buy drugs. It’s true. I would have done precisely that.

My parents and grandparents were always there for me. One reason why I’m still alive is because I always had supportive people in my life.

Starting in middle school, I found adults who could help guide me. I never knew what to call these people and their role in my life until I did the autoethnography. I started calling them “Trusted Adults” (TAs), and there were six of them. The first was my 8th-grade social studies teacher, and the last one was my psychiatrist in Las Vegas. One was a neuropsychologist and briefly my therapist in high school; another was a high school teacher and the substance abuse coordinator in my town (see the article below, which mentions Dave). My Sea Scout advisor and his wife were the other two TAs in my life.

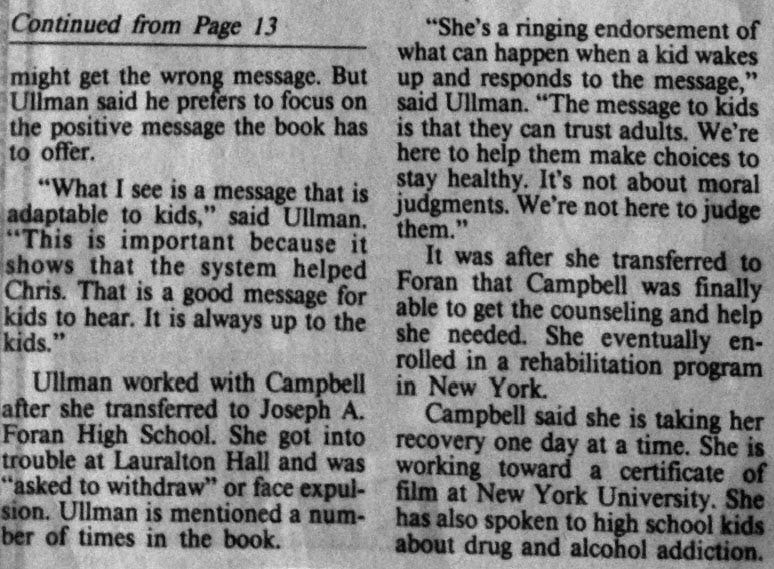

Here’s an excerpt from a newspaper article about No Guarantees that includes comments from David Ullman, one of the TAs.

These people saved my life when I was young. That much comes through in my writing.

Another whole layer of people supported me, and I called them “Supportive Adults” (SAs). Some of them were nearly TAs, but they weren’t in my life long enough. There wasn’t the same intensity with the SAs, and this group included drug counselors, teachers, a vice principal, a therapist, and my first literary agent and editor.

I do sometimes say that it took a village to raise me. In one of Dr. Linda Silverman’s papers, she said it takes a Greek chorus to raise twice-exceptional children.

"Twice exceptional children often feel like failures in school, and usually suffer from low self-esteem. Even if they are brilliant, they tell themselves that they are 'stupid.' It is important for them to have a Greek chorus of supporters who believe in them and continuously reassure them.” (Silverman, 2009, p. 128)2

I didn’t see myself as “learning disabled” but disabled by what I perceived as mental illness. Now, I have the framework of giftedness plus overexcitabilities and neurodivergence to help make sense of my struggles, as well as trauma. I realize now that it’s impossible to have a full grasp of what’s what within my inner experience. There is no clear line of demarcation between giftedness and other types of neurodivergence.

Neurodivergence and Disintegrations

Being neurodivergent and identifying with ADHD, autism, giftedness, or any other difference—often combinations of differences—means living within systems that weren’t built for you. These are ways of being in the world and should not be considered defects. Any of these differences are inherently challenging, and overexcitability can be found within them.

During the autoethnography, while I was learning about Dąbrowski’s theory, I was also learning about the neurodiversity paradigm. It will take many posts to describe my work to understand my unique blend of differences, but I want to follow up with a few more thoughts.

I held back in Overcoming Part 3 and didn’t say that I also wonder if I’m PDA and autistic. PDA technically stands for pathological demand avoidance—I prefer pervasive drive for autonomy—and it makes sense of what has been disabling for me throughout my life. If I’m autistic, it’s this type, along with ADHD.

Thanks to these frameworks of positive disintegration and neurodiversity, I found a way out of seeing myself as mentally ill. I stopped pathologizing myself for having these differences.

I’ve been thinking about the way that the theory has been helping me overcome mental illness-related self-stigma… More and more I’m thinking of OE as a way to embrace neurodiversity. It helps provide a framework for understanding that is centered in creating mental health through a values approach to one’s life. (Journal entry, age 46)

It didn’t help me to identify as being “disordered.” Even now, when I say that I identify with being ADHD, PDA, or autistic, don’t get me wrong—I’m not saying that I identify with them as disorders. There are elements of each that fit with my experiences and lead to increased self-understanding, but I can also see that I’ve had to learn how to live with these neurotypes.

My experience of giftedness and overexcitability has been disabling at times. Denying this would mean denying reality.

“We don’t want the theory to promote ableist beliefs, and yet there has not been a good discussion of how OE might be disabling at all. I’ve spent much of my adult life identifying as disabled—and TPD has helped me reframe many of my beliefs about this. It’s so complex.” (Journal entry, age 46)

I could easily do an Interesting Quotes post from my journals with excepts showing the process of coming to self-understanding and self-acceptance.

“I try not to make excuses for myself anymore. When I make mistakes, I attempt to own them and repair any damage. I take chances. I know that I have a mission in life. All of the work I’ve done since 2014 was meant to shed light on the experience of being gifted and disabled. What’s my disability? This is not a simple question. I have strong developmental potential in Dąbrowski’s terms. But what has that meant for me?” (Journal entry, age 48)

What a blessing it’s been to discover the gifted community. Finally, I found other people who have had similar experiences.

You can expect to hear much more from me on giftedness and disability. There’s much to explore and share from my journals. While working on the Overcoming Self-Stigma series, I removed pages of thoughts that didn’t fit and saved them for future posts.

One of the most fascinating things about trying to understand the past from my journals is looking for turning points from periods of disintegration. I look forward to sharing some of the critical moments and epiphanies I’ve identified. Earlier this year, I wrote,

“Peeling back the layers—that’s what every disintegration does for me. It brings me closer to who I am. The thing that’s cool is that my journals show me the changes over time.” (Journal entry, age 49)

I’ve deeply appreciated the opportunity to share my experiences on Substack with you, and I wish I could better convey how energized I’ve felt by these posts. Thank you for reading.

Michael told me once that it took an “industrial complex” to raise me, and I think there’s some truth to that.

Silverman, L. K. (2009). The two-edged sword of compensation: How the gifted cope with learning disabilities. Gifted Education International, 25, 115-130.

It's interesting to reflect on who my (potential) TAs and SAs are/were.