Overcoming the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness (Part 1)

From Gifted Child to Chronic Mental Patient

I grew up always knowing there was something wrong with me. I realize that sounds harsh, but it’s how I perceived things. The problem was that no one seemed to understand me, and I felt too different and out of sync with everyone else. What I couldn’t appreciate as a child was that it wasn’t one thing that made me an outlier, and there would never be an easy answer to “the problem.”

What I’ve learned in adulthood is that I’m not only intellectually gifted but neurodivergent in other ways. While I no longer need labels outside of Dąbrowski’s theory to understand myself, I recognize that I have an unusual experience of reality that some other people share, and having labels helps us find each other. That’s why I talk openly about being an ADHDer, and I’m honest about resonating with other neurotypes as well, such as autism and PDA.

When I was young, I took the difference between me and others to mean something was wrong with me. By the time I was in high school, I saw myself as mentally ill, and at age 17, I wrote in my journal,

“I am not afraid to admit to having a mental illness. It is something I believe I will always have to deal with. I may not like it, but I have no choice, do I?”

The same summer, I wrote about asking my therapist how to “get better control over my emotions” because “it really sucks to have the mood swings that I have—one extreme to the other.”

I already felt resigned to experiencing alternating periods of depression and elevated moods, which I saw as a mood disorder. That year, I purchased my first copy of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders at the Yale Medical School bookstore after a volunteer shift at the Yale-New Haven Hospital emergency room. Not to date myself, but it was DSM-III-R.

Two and a half years later, I still struggled with what I perceived as mental health issues, but I was seeing different clinicians in another state during my second year at Arizona State University.

It wouldn't surprise me at all to find out I'm manic-depressive. I have such drastic mood swings. I wonder what it would be like to be on lithium? If I could be normal, I'd like to try it. I'd love to find out what my problem is. (Journal entry, age 19)

I didn’t know as a 19-year-old that there was no such thing as medication that would make me “normal.” But it’s clear from my journals that this was my goal for years.

That month, I was indeed diagnosed with bipolar disorder, which would be one of many diagnoses I’d receive in the coming years. I started on lithium but didn’t stay on it for more than a couple of months.

My first book was released six weeks after the bipolar diagnosis, right after my 20th birthday, but it wasn’t something I could enjoy. The story of the book, aptly called No Guarantees, is for another post. But I’ll share the Kirkus Review1 to give you an idea of what it was about:

There’s so much to say about the book and its impact on my life for better and for worse. Or the fact that I was obsessed with dark things like drugs and death at such a young age.

About a year after No Guarantees was released, I made two suicide attempts. I was hospitalized for the first time at age 21, and in Dąbrowskian terms, the ambivalence and ambitendencies during that period of my life nearly killed me. This was when I started to truly feel mentally ill. I was hospitalized several more times over the next five years.

The sheer numbers involved in my history are astonishing—the number of clinicians, the medications, the hospitalizations, the diagnoses. In a relatively short period of time. My heart is heavy as I think of what it was like to go through so many years feeling broken. But I kept writing. There was always the writing. (Journal entry, age 46)

Yes, there was always the writing. Even though I struggled with unilevel dynamisms, the nuclei of multilevelness were there because I had thankfully developed a program of autopsychotherapy and self-education.

As usual, I'm in a mental crisis. I told my mother that I wish I was dead. She told me to meet people my own age, and to do that by maybe volunteering… Tomorrow, I really need to call Social Security and get working on that. There's no easy answer to my problems… It's not going to change, though, these mood swings.

I can't help the way I feel. It's not like I wish this for myself or anything. I have to accept all emotions—good and bad. And I have to deal with them as they come. (Journal entry, age 23)

I started receiving disability benefits when I was 23 years old, which solidified my belief that I was broken. When I told people I’d applied for disability, I heard how difficult it was to get, but not for me. It took six months and was no problem at all because I’d already seen many clinicians, been hospitalized, and taken many medications since that first time on lithium at 19.

Many factors contributed to my decision to lean into mental illness rather than resist becoming a chronic patient. One of the problems was that I started rewriting my story and thinking of the past through the lens of pathology. There’s also significant anger in my journals from the years when I identified as mentally ill.

I absolutely hate the way I've been since I was 21. I've been dull, slow, depressed, morbid, pathetic—no one would've used those words to describe me before that fateful month [when I was first hospitalized]. First lithium, then Depakote, finally Tegretol—why?

When I used to question everything, before I became a spineless victim to mental health, I never just did what I was told. I did what felt right, and apparently I knew what I was doing. That's why I fought so hard to stay out of the hospital that first time—they hadn't had the chance to get my mind under chemical control, yet.

Didn't I remember when I took lithium at ASU? After two months, I said—fuck lithium, give me the goddamned mood swings. After I moved here [to Nevada], they gave me almost three times as much medication as I'd been on in Connecticut. That's fucking insane. I would never do that to a patient. (Journal entry, age 24)

Nine years ago, when I began using the research method of autoethnography as a way of studying, understanding, and healing my past, it wasn’t easy to see how much of my suffering during my 20s was connected to my own beliefs about myself.

But although I saw myself as inherently broken and disabled by age 23, I also had high intellectual self-efficacy and kept trying to return to college. I’d left Arizona State after two years and only 18 completed credit hours, but I knew that I needed to get a degree and didn’t stop trying until I succeeded.

I returned to school several times while also being hospitalized repeatedly.

At age 23, I failed to complete semesters at UNLV and Community College of Southern Nevada.

At age 24, I failed to complete another semester at UNLV.

In 1998, at 24 and 25 years old, I was hospitalized at the Menninger Clinic, which was located in Topeka, Kansas at the time.

At age 25, I returned to school again at Kansas State University from out of state. I still didn’t manage to complete the semester.

I never saw my records from Menninger until I was 41 years old, and that’s good because it was shocking to see how clinicians perceived me. Here’s an excerpt from my first admission, after being very honest about my past and admitting that I’d grown up identified as gifted.

I could do a year’s worth of posts from my medical records alone, and I’m sure I’ll draw from them again here on Substack.

The things I wrote in my journal that first time at Menninger showed that I did want to get well.

It amazes me that I'm doing so well and not obsessing about leaving. Normally by the 4th day I feel like I'm okay and I'm ready to go home and take on the world. But now I know that I need to be here, and if I want to succeed, I have to be willing to do whatever it takes to be well. Being well means not cycling and having stable moods, no behaviors that harm me, having good insight and awareness, being positive, good self-esteem and self-image, and having structure in my life through school, work, or volunteer work. I know that it's progress for me to be able to easily identify and describe what well means to me. (Journal entry, age 24)

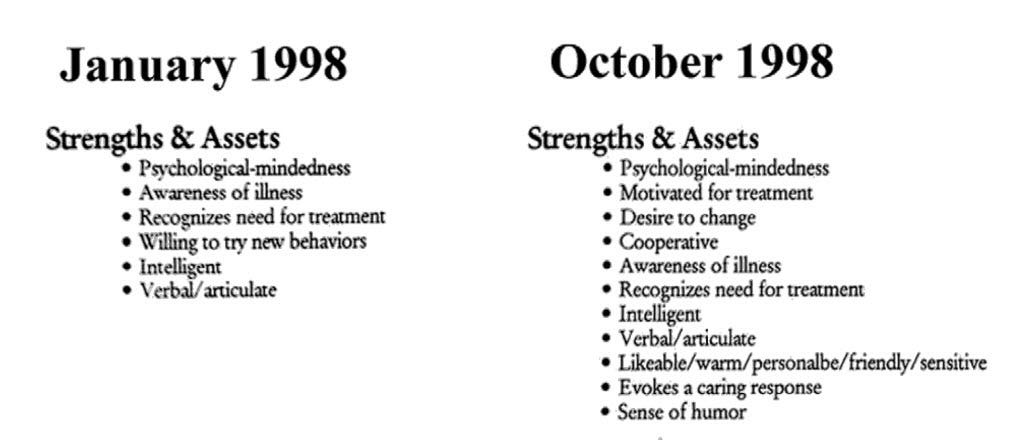

The following image was made from screenshots of my records from the two admissions and shows how differently I was perceived between them. The first time I arrived as a chronic patient from out of state, in January 1998, and the second time, I was admitted as a student from K-State in October 1998.

It’s a little jarring to think that I wasn’t seen as “likeable” or “evoking a caring response” the first time I was at Menninger, but that comes through in what clinicians and staff said about me. And to be fair, I wasn’t as warm or friendly that first time.

I was kicked out of Menninger during the first admission because I used drugs while in treatment. This is a clear example of an ambitendency2, which is a unilevel dynamism in the theory of positive disintegration.

One of the other patients, a local from Topeka, had a visitor who brought her marijuana and methamphetamine. She offered to share with me, and I willingly accepted, which showed I was still ambivalent about getting well.

My guilt about using while inpatient led me to call my therapist back in Las Vegas. She called the staff at Menninger and told them what had happened, which is how they found out I’d gotten high while I was there.

Instead of offering to transfer me to the addiction unit—which is what my psychiatrist back home ordered me to request when I called him in tears—they kicked me out on the street with $13 in my pocket. Fortunately, my parents wired me money and helped me get a hotel room and a flight home the next day.

I did my best to see the positives.

One good thing about Menninger is that they gave me two weeks' worth of pills. That was good of them, even if they were assholes to me. I can understand why they'd be pissed… I'm proud of myself. I'm an adult, and today I acted like one. I was very angry and disappointed, but I shook my doctor's hand and left without any problem.

Several times over the past week, and especially today, when the doctor told me that I'd be dealing with my disease for the rest of my life, I was thinking—oh yeah? You should've seen me six months ago or a year ago. I've come a long way, and even though I slipped up and got high, no one can take that away from me. And I'll continue to grow because I know what I want from this life. (Journal entry, age 24)

It’s important to understand in these posts about self-stigma that I expected to take medication for the rest of my life. During my 20s, it was drilled into my head that I was mentally ill and would always be that way.

That turned out to be incorrect. This month—August 2023—marks six years since I’ve taken psychiatric medication.

During the second admission to Menninger, things were very different than they were the first time. My time at Kansas State was brief and tumultuous. First, I was kicked out of my dormitory for threatening another student because I thought she called the police on me for smoking weed.

It’s also important to understand how difficult it was to see my own bad decisions during the autoethography. Until I discovered Dąbrowski’s theory, I didn’t know the term ambitendency, but my self-sabotaging behavior often got in the way of success.

Even during the autoethnography, I was pathologizing myself and only seeing the past through a deficit perspective.

I was only at K-State for two months, which is a stunningly short amount of time to fuck up so many times. It was mind-blowing. As if I was actually incapable of making a good decision. Like some part of my brain—the decision making area—was damaged! It was! I have ADHD, and therefore, already had issues in the prefrontal cortex, including problems with reasoning, self-control, and decision-making. (Journal entry, age 41)

In Dąbrowski’s terms, I experienced unilevel and multilevel dynamisms together for years during my 20s, but the problem was that the unilevel ones were often stronger. And it was extremely difficult for me to stop self-medicating by using street drugs.

In Part 2 of this series, I’ll share about leaving the roles of mental patient and addict, moving to California, and starting a new life.

In Part 3, I’ll discuss autoethnography as a method of autopsychotherapy and the life-changing impact of finding the theory of positive disintegration during my “giftedness and disability” literature review.

Thank you for reading. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber and supporting this work.

The ISBN on the Kirkus Review was incorrect and should be 0-02-716445-4.

“Ambitendencies—changeable and contradictory courses of action, self-defeating behaviors, irreconcilable desires.” (Dąbrowski quoted by Piechowski, 2017)

Ambitendencies - are these found at all levels of disintegration?