Overcoming the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness (Part 3)

The Value of a Non-Pathologizing Framework

The first two posts are here: Part 1 and Part 2.

When I planned this series of posts, the goal I had in mind was to convey how dramatically it has changed my life to discover Dąbrowski’s theory. I wanted to provide more context for our podcast listeners. The challenge with telling my story is always that there are so many layers and connections that I can never capture it all.

After hitting publish on the first two parts of this series, I made peace with not describing the traumas I’d experienced. The biggest one was my father’s alcohol use and the way that he drank so much it killed him.1 I experienced other traumas as well, and it wasn’t until my 40s that I began to understand the impact of these experiences on my life.

Please forgive me for doing this. We’ve got to skip several years to start with the critical moment when I discovered autoethnography.

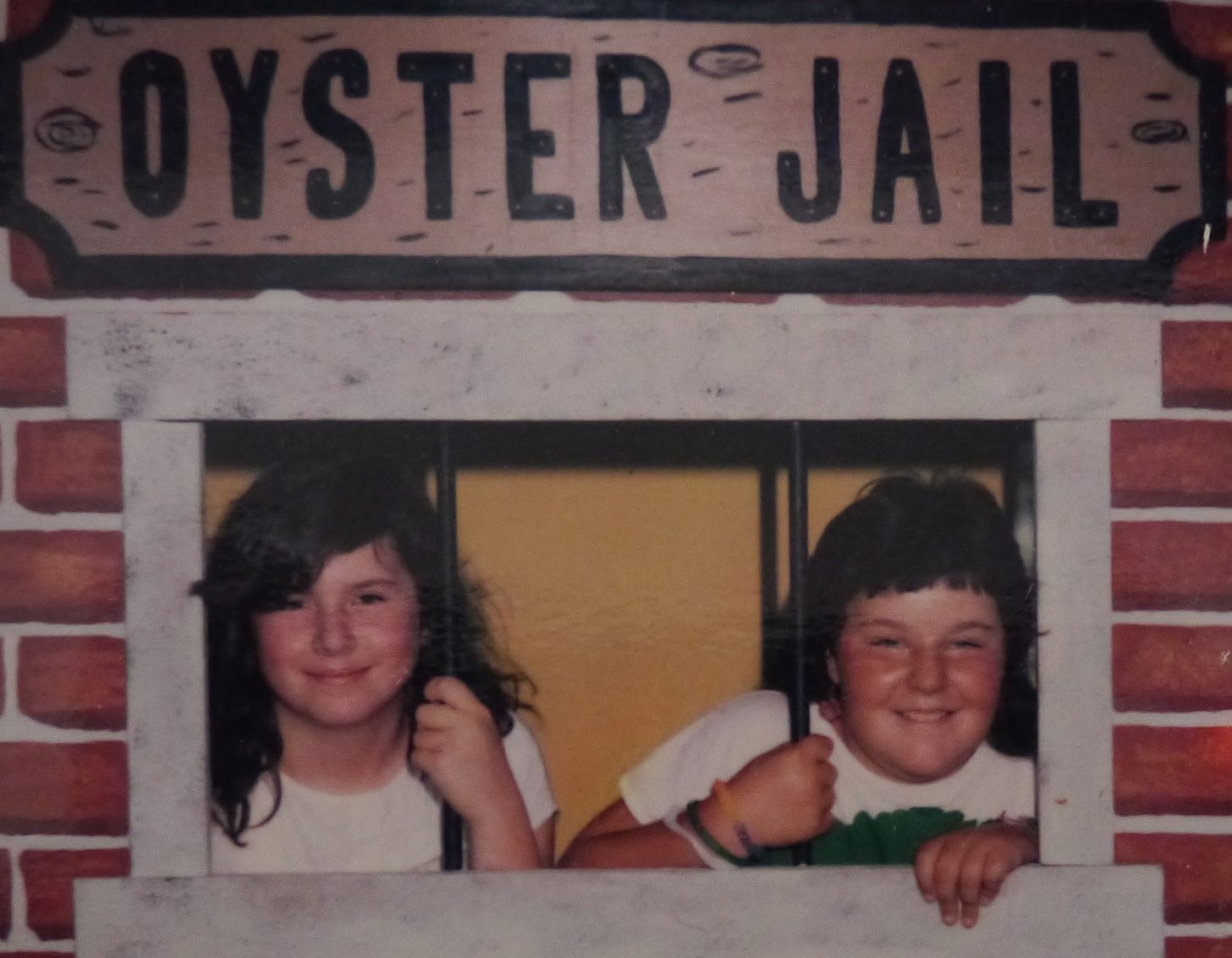

At the beginning of 2014, I went home to Connecticut for a funeral and learned that my cousin—who was a year younger than me—was dying. Here’s a photo of us as kids at the 1985 Milford Oyster Festival.

Her name was MaryJo, and we were close during childhood. Her illness threw me into an existential funk that led to an intense desire to understand how I managed to survive mental illness and addiction.

A doctoral student in psychology at the time, I’d completed my coursework and was at the beginning of the dissertation process. While reading about qualitative methods, I discovered autoethnography and knew I needed to pursue a personal research project that year.

What is autoethnography? Here’s a definition from Adams et al. (2015)2:

“Autoethnography is a qualitative research method that 1) uses a researcher’s personal experience to describe and critique cultural beliefs, practices, and experiences; 2) acknowledges and values a researcher’s relationships with others; 3) uses deep and careful self-reflection—typically referred to as “reflexivity”—to name and interrogate the intersections between self and society, the particular and the general, the personal and the political; 4) shows people in the process of figuring out what to do, how to live, and the meaning of their struggles; 5) balances intellectual and methodological rigor, emotion, and creativity; and 6) strives for social justice and how to make life better.” (p. 2)

Four years earlier, I’d written a second autobiography, which was a decision that had haunted me even though writing helped me work through my father’s death and leaving my first real career in social work. When I discovered that it was possible to use research methods to study my life, I knew that this was the piece I’d been missing. I knew there were still unhealed wounds and things I didn’t understand about myself and the past.

Aside from finding autoethnography, the other big thing that happened around this time was learning the term twice-exceptional (2e), which means gifted and disabled.

Like so many people, including educators and mental health professionals, I thought that giftedness and disability were mutually exclusive. When I was in my 20s and diagnosed with multiple disorders, I assumed that gifted was a label that no longer applied to me.

The first reading I did from the field of gifted education was by Dr. Linda Silverman, who happens to be based here in Colorado. Discovering her work opened the door for me to get curious about the lived experience of giftedness.

It’s hard to believe, but as I write these words, I realize that it was ten years ago this fall that I read Linda’s work for the first time. I still remember the articles I read first, and I will do an Interesting Quotes post soon to share some of her wisdom. [Edited to add: Interesting Quotes, Vol. 8]

At the time I was reading her work, I was also taking medication for ADHD and discovering how life-changing it was to actually treat that issue. As you know from my other posts in this series, I struggled for years with drug use. Well, guess what? It’s no coincidence that I gravitated toward self-medicating with stimulants. Taking Adderall at age 40 showed me clearly that I am an ADHDer, and it called into question the other diagnoses I’d been given.

I dove willingly down the rabbit hole of reading about giftedness and 2e, feeling amazed by what I found in the gifted education literature—a field I’d never known existed before that point, despite specializing in education as a doctoral student in psychology.

Life-Changing Research

As soon as I started reading about autoethnography, it felt familiar and perfect for the kind of writing and self-reflection I was engaged in at the time. I immediately saw that it helped me connect with the broader context I’d been missing in autobiography while providing guidelines such as ethical considerations.

Each time I’d engaged in autobiography, it was while emerging from a traumatic event (or more than one) and trying to process and integrate my experiences. In retrospect and from a Dąbrowskian perspective, I consider my books the products of autopsychotherapy efforts. I was trying to make meaning, understand, and heal. I wasn’t placing the events or myself within a broader cultural context and had little objectivity, rigorous self-examination, or self-evaluation.

As a student already in the dissertation process, I’d had some training in research methods and had a very different perspective than I’d had while writing about my life in the past. I knew that I could take my personal data, study it as a researcher, write a paper based on what I learned, and present at conferences.

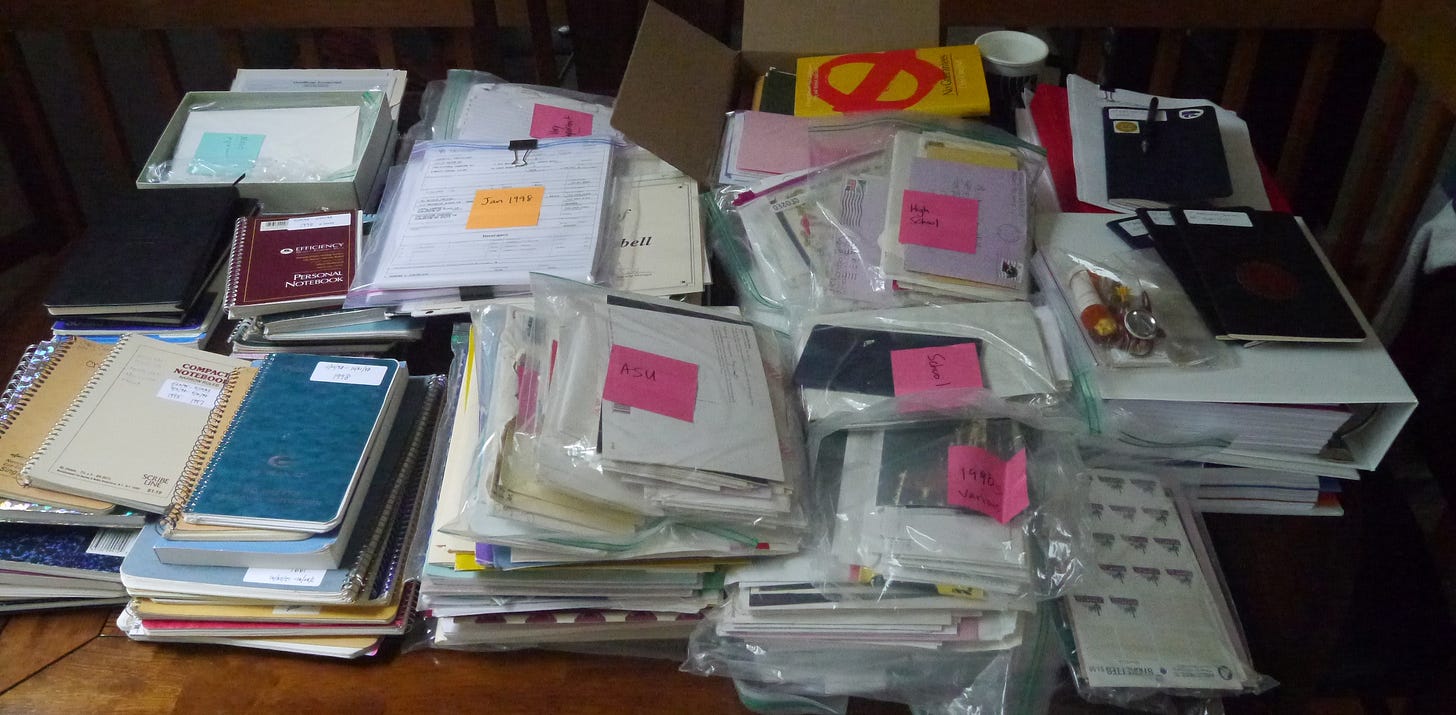

First, I had to take stock of my personal data and organize it. Here’s a photo of the pile I made of everything I’d collected and labeled.

You can see that it’s an assortment of journals, books, letters, medical records, and other assorted documents and memorabilia from my past.

There are many different ways to do and present autoethnography, and I studied analytic, evocative, and interpretive styles. I documented my process meticulously and threw myself into this work with an urgency and one-pointedness that I’d never experienced before.

Let it be known that I plan to share more posts about this type of qualitative research. While I also have experience with other types of qualitative inquiry, such as grounded theory and phenomenology, my passion lies in autoethnography. But I don’t have space in this post to go into the weeds about my methods.

What was the research question guiding this work in 2014?

“When I began this study, I wanted to know why I was able to succeed and leave the sickness role at 26. How did I go from chronic mental patient to doctoral student? The odds had been stacked against me, and I needed to know what had facilitated my growth.” (Wells, 2015)3

My perspective at the time was grounded entirely in the medical model. I still saw myself as essentially broken even though I was open to considering myself from the standpoint of intellectually gifted as well as mentally ill.

I had never even heard of being emotionally or spiritually gifted, but those terms awaited me in the work of Dr. Michael M. Piechowski. Admittedly, during the initial study in 2014, it was too much to take in the gifted ed literature and explore the theory of positive disintegration in-depth. But I kept returning to one chapter by Michael in particular, which I’ve already described in Interesting Quotes, Volume 2.

The reflective journals I kept during 2014-2015 were extensive, and I wrote more than 94,000 words. It was, in many ways, a grueling process, and not only did I scan, type, and code my journals from 1989-1999 and my medical records, but I also took trips to Nevada, Kansas, and Connecticut and interviewed a dozen people who’d known me when I was younger.

'“Yesterday, I realized that what’s happened in the past—in terms of my identities based on mental illness and addiction—no longer applies to my current life. I don’t need to feel like there’s a scarlet letter on my chest, identifying me as characterologically flawed. That’s all part of the stigma aspect of this research. So much trauma occurred—unintentionally—during my treatment experiences.” (Journal entry, age 41)

By studying my life as a researcher, I was able to create some distance from the past and the traumas I’d experienced. But I still shed many tears while realizing how poorly I’d remembered my younger self. It turned out that my memories weren’t as reliable as I’d thought. And not only had I been badly misunderstood in treatment, but I was often the worst offender, misunderstanding myself and my motivations.

One thing I realized during the process is that I’m very intense compared to the norm. That word came up again and again in interviews.

I also had to come to terms with my selfishness—in the past and the present. I had many moments of astonishment with myself, dissatisfaction with myself, and a clear view of how far I still had to go in my development, which Dąbrowski called inferiority toward oneself.

My expectations of others were often based on my desire to reconcile the past, and I learned that not everyone wanted to engage in discussions about how things used to be. I realized that I needed to learn how to get out of my own head and be more present for my loved ones. It would take a few years before I made real progress in that area.

The first round of autoethnographic research culminated in two conference presentations where I spoke to audiences of academics about my work. I described my history as someone who identified as gifted and mentally ill.

I had a massive panic attack before the first conference. Was I really going to stand up and talk about my terrible history of mental illness and addiction? Indeed, that was the plan. This is what I said to that first audience:

“Looking at me, or talking with me, doesn’t betray my disabilities… I’ve been hospitalized ten times for bipolar disorder, and I’ve been addicted to drugs. I can pass for normal, and that’s what I’ve been doing for fifteen years—since I chose to quit my career as a mental patient.

It would be a simple thing to never admit to my devalued statuses—to get my doctorate and turn my back on the people still struggling the way I did for so many years. Most people don’t talk about their experiences with mental illness because of shame.” (Wells, 2014)

It went very well, and I had an engaged, thoughtful audience who asked great questions. Some folks even shared their own experiences with me later in the hallway.

The presentation for the second conference was done a little differently, with the perspective I’d gained from the first session a few months before. I talked more specifically about my experiences in mental health treatment and the powerful therapeutic alliance I’d had with my psychiatrist in Las Vegas.

Afterward, I wondered where to go next with my work. I re-engaged with my dissertation study on the lived experience of parenting twice-exceptional children. But I couldn’t stop studying the intersection of giftedness and mental illness. I started attending conferences and meeting scholars in the field of gifted education with an eye on finding a mentor.

Rethinking Mental Illness

Unlike many people I’ve met in gifted ed, I didn’t love the overexcitabilities when I first learned about them. The only framework I’d had for understanding myself before 2014 was the DSM and mainstream psychiatry. It wasn’t easy to accept positive disintegration as an alternative perspective.

It took time for me to absorb the gifted literature and explore the areas that seemed most applicable to my life, such as positive disintegration. Meeting people from the field accelerated the process. In 2015, I attended conferences, such as Confratute and SENG, and met several scholars, practitioners, and other parents and writers in the gifted community.4

The self-stigma from perceiving myself as mentally ill followed me everywhere. I worried about telling the truth about my history because I feared people’s reactions. Would they be willing to talk with me? Would they be less likely to consider me as a potential collaborator?

After two years on Adderall, I found myself questioning the bipolar diagnosis I’d embraced for years. Had ADHD been the issue all along? Autoethnography allowed me to explore the years I’d always viewed as periods of mental illness through a new lens.

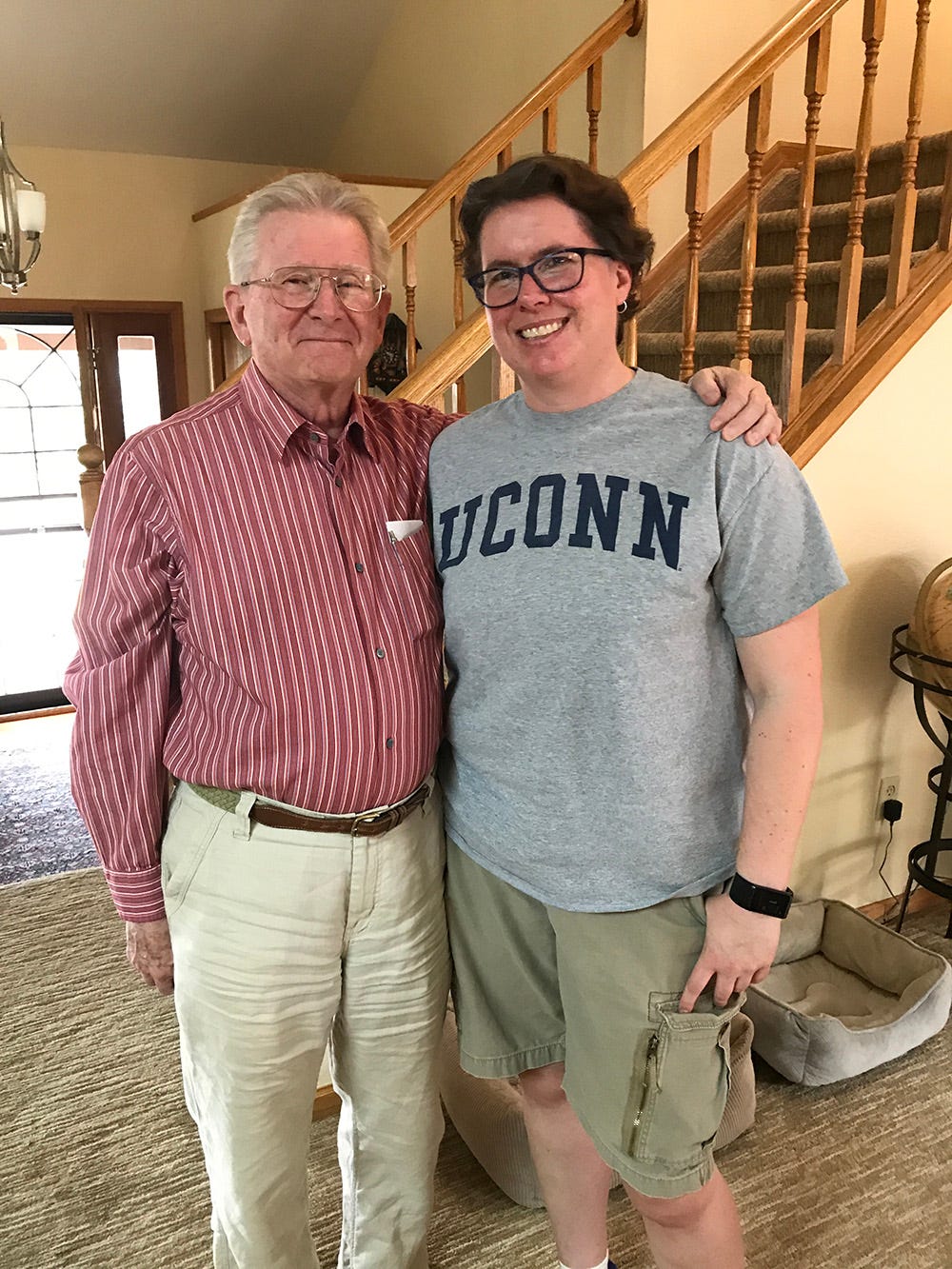

In August 2015, I met with Linda Silverman at the Gifted Development Center, and we talked about my history, my son, and where I might go next with my work. The big question for me was the bipolar diagnosis, and she gave me some helpful suggestions.

Linda asked if I’d ever examined my journals and looked at the patterns of my moods without searching for pathology. She asked if I’d ever been able to look at my past without assuming I was mentally ill. I told her no—I had only searched for evidence to support my existing beliefs that I’d been sick.

I described some of my experiences that were considered manic episodes. Many of them were directly related to my ability to produce mountains of writing in short periods. For instance, writing a book at the end of high school in just a few months had been considered the product of a manic episode by a therapist I’d seen years later. Similarly, I’d been put on antipsychotic medication in 2008 after admitting to my psychiatrist that I’d written hundreds of pages since seeing him two months before.

Slowly, I realized that I’d never been able to view myself and my past without the expectation of mental illness. This is how I’d seen myself since I was an adolescent, and I’d never questioned it.

Also, when I interviewed the people who had known me when I was young, I learned that they had not perceived me as mentally ill. My former vice principal from high school talked about how unusual I’d been compared to other students, but he pointed to my intelligence and leadership ability. I’d expected to return home to stories about how “crazy” I’d been perceived, but that’s not what happened.

I decided to stop taking the mood stabilizer Lamictal but continued taking Adderall XR to treat ADHD and Klonopin for anxiety.5 At that point, I had been taking medication for more than 20 years, with the only exception being the time when I was pregnant and breastfeeding.

“I stopped taking Lamictal today. My plan is to be aware of my moods much like I already am aware—but more purposefully. What I wrote and what other people perceived isn’t helping me with the bipolar question. There’s no “test” for bipolar disorder—and while there also isn’t one for ADHD, there are instruments available which indicate that I do have ADHD.

The main thing is—does the medication make a difference? Adderall clearly does. I’m not as sure with Lamictal. Is it true that the bipolar label was useful at one point, but no longer necessary? It feels funny to reject a label that was so carefully examined during my 20s.” (Journal entry, age 42)

Going off of Lamictal went very well. I monitored myself and my moods and found no reason for concern during the first few months. That was eight years ago last month, and there’s still no reason to think I have a mood disorder.

The other important thing that Linda told me was that I’d find answers in Dąbrowski’s theory and that I should continue reading and studying it in depth. She encouraged me to consider submitting a proposal to the 2016 Dąbrowski Congress and said that I’d find my people in that community.

Linda also talked about Michael Piechowski. She described how much she loved his writing when she first came to it, and that conversation encouraged me to return to his work.

A New Framework

I’ve written a little about getting to know Michael and his work in 2016. Right away, when we were writing to each other, he challenged me to think about myself and my past differently. In his work, I recognized myself and realized that he was describing what I’d seen as symptoms of mental illness as strengths.

The change in my beliefs about myself and the past didn’t happen overnight but in many moments of slow realization and revelations.

Two years after I stopped taking Lamictal, in August 2017, I decided to stop taking Adderall XR and Klonopin. I needed to know if I could live without psychiatric medication. As I developed my expertise in the theory of positive disintegration, I felt the urge to experiment with myself and better understand my experience of overexcitability.

“I am finally free. For the first time since I was 19 years old, I do not feel I require psychiatric medication. I already feel more intense. But I feel a need to move forward as my authentic self. Like I have chosen my path.” (Journal entry, age 44)

I don’t want to give you the impression that coming off of these two drugs was easy. Unlike Lamictal, which I discontinued without noticing any real changes in myself, stopping Adderall and Klonopin was challenging.

The first week without Adderall was highly frustrating, and I found myself distracted by everything around me and within my inner experience. Living without Klonopin was also very challenging, and I came off of it gradually over three months. My experience of intensity ratcheted up to a degree that was uncomfortable and tough to manage.

How did I get through it? I asked Michael for help, and he gave me some suggestions for developing a personal mindfulness practice. I drove to Wisconsin for a visit, and he recorded three psychosynthesis exercises for me. These exercises opened the door for me to be able to meditate, but it took more than a year before I had any relief.

“I need to write about what it's like to be free of labels and pills, but how it doesn’t mean I don't struggle. It's not that the struggles haven’t always been real. I guess I'm feeling now, in middle age, that I want to search for inner resources and try to deal with it from new angles. There's a good reason why I was willing to accept ADHD as a label. I can see why I found Adderall so helpful. But I feel so much healthier without Adderall.” (Journal entry, age 45)

During this time, I started thinking of myself as Michael’s student, and I dedicated myself to studying the theory and becoming a scholar in this area. Getting to know him was an intense, complicated process, and one that I plan to share much more about in the coming years.

After postponing my dissertation for three years to explore my history through autoethnography, I was finally able to return to it during this time when I went off of meds. I defended my thesis on June 29, 2018, and my degree was officially conferred one year after stopping Adderall.

Liberation

My story is not unique by any means. Many people have come to the theory of positive disintegration and felt seen and mirrored adequately for the first time in their lives. It’s a powerful experience. Many of our podcast episodes include guests describing what it’s like.

Why do I talk about the past and my story? I’m an extreme outlier because I’m multi-exceptional, meaning I have multiple intersections of identity. Depending on who defines it, I’m highly gifted or even profoundly gifted, and I’ve long embraced the ADHD label and still accept it, even though Michael will never agree. I’m also nonbinary, which is another term I didn’t learn until middle age, and it helped me make sense of why I’ve always felt so different. For simplicity’s sake, I say I’m neurodivergent because that seems to cover everything people need to know.

It took years of searching and inner work to finally make sense of my life, accept myself for who I am, heal the past, and move forward with what I’m meant to do in the world.

I don’t see myself as mentally ill anymore. I’m different, but I’m not defective. It took so many years to figure that out. My job now is to carry this message to others and let them know they’re not broken.

“It’s strange to reflect on the way I took medication for more than 20 years and believed that I had an incurable mental illness that could only be managed with pills. It’s only been 4 years since I began questioning, and stopped treating bipolar disorder. The time since 2017 has been spent remembering—or relearning—who I am without pills. I haven’t been very patient with myself.” (Journal entry, age 46, 2019)

We’re all on our individual journeys. What worked for me may not work for others. We each have our own paths and must engage in our own processes of self-discovery.

If you are currently suffering, take heart. Things can get better. Be kind, patient, and gentle with yourself while you create your new path. Remember that the way out of suffering is through your values. It’s up to each of us to choose to live and have faith in ourselves and our ability to navigate the world. No one can give that to us. It’s something we have to find within and act on.

I used to be my own harshest critic. My expectations were too high, and they were influenced by internalized ableism and ignorance about multiple aspects of myself. All I saw were my flaws and failures, and I had no confidence in myself. I was convinced that there was something inherently wrong with me.

“I feel so great about where I am right now. I used to live with so much self-doubt, under a cloud of fear and anxiety. I worried about being mentally ill—waiting for the next depressive or manic episode. I want to find a way to share this difference. It has been so liberating to discover Dąbrowski’s theory. I’m still searching for where to spread the message.” (Journal entry, age 47)

I didn’t see how much I was hurting when I was young until my mind would allow me to see it. That happened during the autoethnography.

“I found some notes from the autoethnography—from early 2015—and here’s one that’s undated and interesting: “It’s good that no one could’ve predicted I wouldn’t really feel comfortable as myself until I was 41. But this past year has been transcendent in every way. Finally—after years of trying to understand—I know why I’m so different. And not just why—it’s more than that. I know why I’m different, and there’s nothing wrong with who I am.” (Journal entry, age 49)

Thank you for reading and taking the time to learn about my story and this journey of self-discovery and transformation.

The word alcoholism is considered problematic, and I’m still working on avoiding it in my writing. As someone who was an addict, I have opinions on this issue, but I’m going to save them for another post. I talked about my father and his alcohol use in Episode 34.

Adams, T.E., Jones, S.H., & Ellis, C. (2015). Autoethnography. Oxford University Press.

These excerpts from 2014-2015 are from my presentations at the Qualitative Health Research Conference (2014) and The Qualitative Report (TQR) Conference (2015).

I talked about attending SENG 2015 in Episode 31 with Celi Trépanier.

In the future, I will say more about the experience of going off of medication. I want to be clear that I did this with support, and I’m not suggesting it’s the right answer for anyone but me. Please do not go off of medication on your own without the help of your prescriber.

Chris, this is wonderful and brutal. It breaks my heart that you would have to work so hard to get where you are and elucidates that all the wrong people end up with imposter syndrome. I'm the opposite of you in so many ways, but your story resonates profoundly- for me I was anti mental illness, denying there was anything "wrong" with me and didn't start medication until my mid 30's after the birth of my son- largely precipitated by post partum depression (but that I can now see through the lens of TPD) that had me in a state of extreme psychosis. I was faking it until I could make it, then medication "magically" became a set of crutches to hold me up and heal. And the brain space it cleared was a revelation.

But it was temporary. I kept itching toward understanding myself and also knew there was *more* to it. That sent me on a dalliance with pathology and I feel lucky as hell that it "only" took a decade to detach from that and move toward the truth of my inherent existential intelligence.

I didn't have a "career" or a "proper" education so spent decades gaslighting myself into believing I didn't know what I was talking about. Bumping into you, at this crossroads in my journey gives me so much hope and optimism in US, in the reach of TPD and of helping make sense of myriad life experiences for ourselves and our communities. What a gift to the world you are!