How Do Highly Gifted Adults Show Developmental Potential? Part 1

Gifted Adults in Their 40s and 50s - Environmental, Familial, and Personal Factors

We’re excited to share a three-part series of posts from Dr. Deborah Ruf over the next week. Chris is traveling to Wisconsin to visit Dr. Michael M. Piechowski and will likely take a break from posting during their trip. Thank you, Dr. Ruf, for allowing us to share your work with our subscribers! View the original post and subscribe to Gifted Through the Lifespan.

I re-edited this post when I discovered I had indeed finished it. It became a full chapter in Morality, Ethics, and Gifted Minds, edited by Don Ambrose and Tracy Cross, by Springer Publishing.[1] I have now included a full PDF link to my chapter in the book at the end of each of the three posts by this name, Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3. I’ve embellished this first part and the writing is a more friendly form from the aforementioned book.

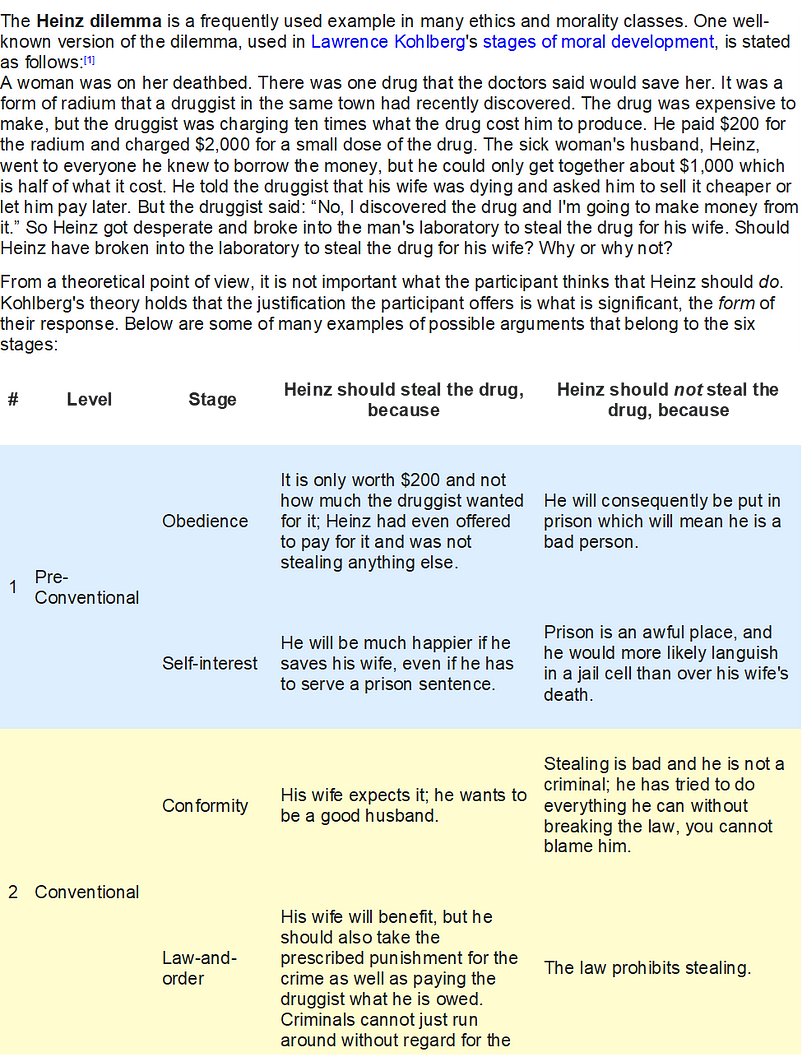

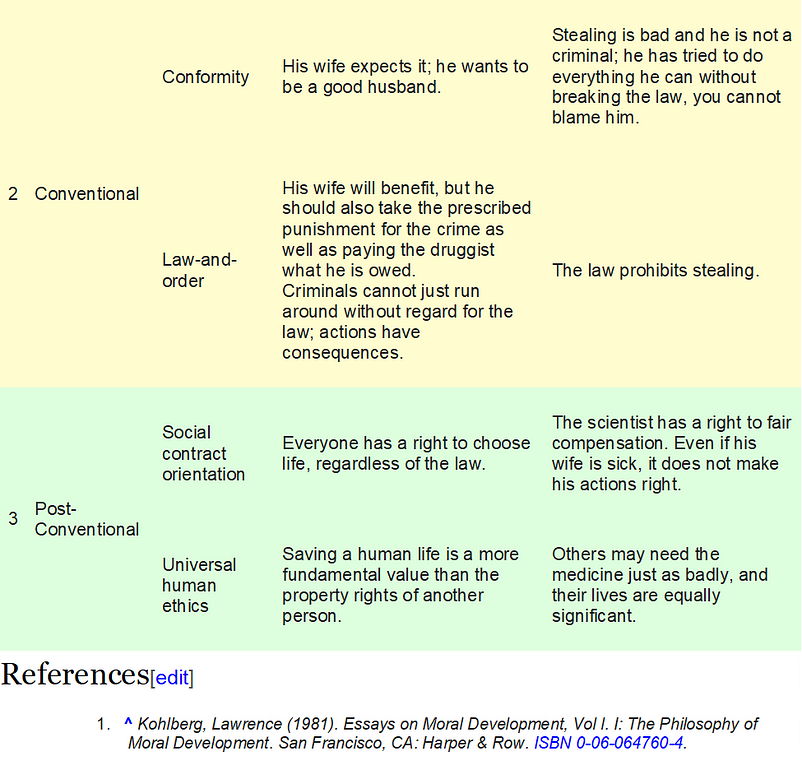

My chapter is about developmental potential vis-à-vis Kohlberg, [2] Maslow, [3] and Dabrowski. [4] I probably forgot about this chapter because — since then — I got well into the weeds myself on developing my own inner growth and potential. Who had time for more remembering publications at a time like that? I was in my early 60s. (I think age references help us to see how far along on the inner growth journey one is likely to be).

This post — and the next two or three on this topic — also came from my finally finished on the last day of 1998 doctoral dissertation study, Environmental, Familial, and Personal Factors That Affect the Self-Actualization of Highly gifted Adults: Case Studies (41 of them).[5] The subjects are all Baby Boomers born between about 1946 to 1966.

This post is a deliberately intended explanation for the die-hard Searchers among us. I will provide the missing tables mentioned in Part 1 as they become understandable in later posts from this study summary. Treat it like a serial.

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Participants volunteered in response to the announcement of the Gifted Adult Study via a mailing list of the Minnesota Council for Gifted and Talented and an ad in America Online. Numerous highly gifted adults were also nominated by friends and colleagues. Subjects, then between the ages of 40 and 60, were selected on the basis of a self-reported 99th percentile test score of intellectual ability. A variety of measures were in evidence (see Table 3). A number of the participants agreed to participate because their own careers are aligned with gifted children and adults and they wished to contribute to a study that particularly emphasized the treatment and outcomes of highly gifted individuals. Out of 183 who volunteered, the final selection comprised 41 participants: 20 men, 20 women, and one acknowledged transgendered person. Twenty-seven are examined here in search of the understanding of the transition from unilevel development (Level II) to multilevel development (Level III).

METHODS

The participants answered questionnaires specifically designed for this study: evidence of giftedness (2 pages long), childhood experiences (11 pages), adult life (11 pages). Another questionnaire was sent to the parents asking about the participants’ childhood (Ruf, 1998, 2009).

The participants filled out the Defining Issues Test (Rest, 1979) to assess level of moral reasoning. An outline of the scoring scale is presented in Table 1, which will show up in a later post from this serial.

Just to pique your interest, I’ve included one of the most famous of the “dilemma’s” from the Defining Issues Test here. Before you look past the words “Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?” test yourself to see what you would have answered. It is not in my original chapter of the Ambrose and Cross book.

DATA ANALYSIS

The written responses of the participants were evaluated for indications of self-actualization along with information on education, growing up, occupation, and so on.

Primary Sorting Categories

The following categories showed usefulness in explaining levels of adult success, happiness, satisfaction, and levels of inner development:

• Childhood abuse

• Tone

• Searcher, Nonsearcher, Neutral

• Counseling or therapy

• DIT P-score

It was initially theorized — by me — that subjects who had been abused would have more difficulty self-actualizing. Here, abuse is meant to indicate any treatment, as perceived and reported by the study participants, which made them to feel unloved, or unworthy of love, respect, or admiration. Although some abuse is intentional, it need not be intentional to cause harm. The following kinds of abuse were considered:

1) Emotional — putting child down, criticizing, especially suggesting the child is unwanted

2) Physical — including excessive punishment

3) Sexual — including exposing child to sex inappropriately

4) Spiritual — using threat of God’s wrath

5) Neglect — parent caught up in own problems

6) Ignorance — good intentions but stupid actions that result in emotional harm

Categorizing the cases based on abusive versus nonabusive backgrounds still did not explain apparent differences in adult-level happiness or self-actualizing outlooks and behaviors. Abuse was not verifiable by the participants’ written self-reports since some subjects described abusive circumstances but denied they were abused. Other subjects realized that the parenting they received was not optimal but because they always felt loved and supported, they did not feel it damaged them. As a result, abuse as a category was assigned only when the subject clearly stated that he or she felt abused.

Tone was a new sorting category: “A particular mental state or disposition; spirit, character or tenor” (Random House Unabridged Dictionary, 1987; definition no. 14). I used it as shorthand for conveying the degree of satisfaction and contentment in each subject’s life. One can compare a subject’s Tone with intellectual level, DIT score, and background experiences. The Tone scale was modified several times to allow for the many moods and viewpoints that the subjects exhibited. The Tone Scale is as follows:

Tone 1: subjects say they are happy, content, satisfied; have a positive outlook

Tone 2: same as Tone 1 but also reveals some sadness or disappointment

Tone 3: not possible to discern subject’s tone or the subject seemed to be in emotional limbo, neither content nor particularly discontent

Tone 4: made statements that they are not at all happy or content; filled with many unresolved feelings

Tone 5: subjects write that they are very angry or resentful

Counseling or psychotherapy can affect a person’s life significantly and thereby contribute to both DIT and Tone scores. Counseling appeared to be associated with higher DIT scores, but not with adult happiness to any strong degree. It is possible that therapy didn’t necessarily cause higher DIT-type reasoning but was sought by people who were already open to changing themselves, people whose inner search pushed them farther in emotional development. Consequently, the Searcher category was added. Phrases and expressions corresponding to Dabrowski’s process of “positive disintegration” were viewed as initial evidence of Searcher behavior.

Positive Disintegration — This is a term created by Kazimierz Dabrowski to describe an episode of emotional and intellectual crisis precipitated by a severe cognitive dissonance that leads to new personal insights and viewpoints. The subject is presented with information and experiences that do not make sense in the context of presently held global views about the self and one’s role. The intellectual interference is so strong that the person’s resistance to change breaks down and causes strong, sometimes severe, emotional discomfort. If the person rationalizes, ignores as an aberration, or intellectualizes the incompatible data, emotional recovery may take place, but the person remains essentially unchanged, and according to Dabrowski’s developmental theory, at a low level of emotional development. If the person examines and internalizes the new data, incorporates it into the self, even takes time to feel the loss of old ideas and values, the emotional recovery is positive and growth-inducing. The experience of tearing down old notions and building new ones is the process that changes the person (Dabrowski, 1967).

Searcher — Searchers are still actively deciding who they are and who they want to be. Searchers tend to see many sides to any issue. Searchers examine and re-examine situations, themselves, others, and are open to changing their views if new, convincing information becomes available. Searchers may or may not be self-actualizing in either their careers or intrapersonal (inner) lives. Such individuals may go through periods of emotional turmoil called “positive disintegrations” as they strive, consciously or unconsciously, to reach their personality ideal, their best overall selves. Their case material shows evidence of emotional and ideological struggles.

Nonsearcher — Identity exploration is not reported by the subject as an active concern. Nonsearchers give evidence of either identity foreclosure or identity achievement, as described by Erikson (1968). Marcia (1980), elaborating on Erikson’s work, described identity foreclosure as the situation when adolescents do not experiment with different identities, but simply commit themselves to the goals, values, and lifestyles of others, usually their parents. Josselson (1991), in her study of women’s identity development, described identity achievement among her subjects as being a self-tested and self-selected identity independent of parental choices and quite stable.

Not Clear — Previously called Neutral, someone who is neither clearly a Searcher nor a Nonsearcher, which means that there wasn’t enough anecdotal evidence to categorize the subject as either a Searcher or Nonsearcher. The Not Clear designation means that the person might very well be either, but — based on the written record the subject provided — it is impossible to discern and the categorization remains a question mark.

Some Nonsearchers in the study are people who may be self-actualizing in a career sense in that they are productive people who live and work at a high level of competence, presumably up to their potential. This is not the same as the inner emotional maturity that is normally achieved after extensive identity exploration and adaptations. Other subjects described as Nonsearchers say they are underachieving but accept the status quo. Hence the following distinction of two kinds of self-actualization:

Career Self-Actualization refers to an identity formation without going through a developmental crisis. These people are successful and fulfill the role of good, law-abiding, socially responsible members of their society, but have closed off the possibility of any need to make significant changes in themselves. This common conception of self-actualization does not reflect Maslow’s description of self-actualizing people.

Inner Self-Actualization refers to people who experience inner transformation after undergoing one or more developmental crises, and who have found a complexity of viewpoint and thought that comes from inner growth that continues to allow for significant personal changes. They may or may not appear to be successful in a career or monetary sense. They meet Maslow’s description of the self-actualizing person; and they meet Dabrowski’s description of Level IV of emotional development (Brennan & Piechowski, 1991).

This May Be the Most Important Finding of the Study

The final sorting category was the DIT P-score, where P stands for “principled” thinking. It emerged as an important indicator of potential for more abstract, complex emotional reasoning. Referred to as emotional growth or maturity, it indicates an openness to change, particularly inner change. Although it was initially hypothesized that all highly gifted subjects would score well above the population average of the DIT, the subjects’ score range was quite wide despite their uniformly high intellectual and educational levels (Ruf, 2009).

Although score trends showed a general progression of DIT scores corresponding to the advancing complexity levels of moral and emotional reasoning as outlined by Kohlberg and Dabrowski, there was considerable evidence that not every case fell neatly in line. The difficulty was always related to the definition of the term Searcher. Clearly “searching for answers” is not the same as being open to new information that can totally transform one’s viewpoint. A Searcher continues to be open; someone who is not a Searcher — or no longer a Searcher — stops searching once the “answer” is found.

A DIT score below 65 appears to indicate a person who is most likely not a Searcher, although some cases with scores above that level were categorized in the original study (1998) as Neutral (Not Clear) if there is no clear or specific evidence of being Searchers.[i] The possibility arises that they are potentially multi-level but their DIT score does not tell the whole story. The DIT author, Rest, never related self-actualization to his DIT results, merely higher-level moral reasoning. Subjects who showed negativity, bitterness, resentment, or resignation were categorized as Nonsearchers.

Evidence of being a Searcher or Nonsearcher has proven to be the most salient factor in separating high emotional reasoning levels from the low ones. Positive disintegrations proved to be more difficult to count or verify; and there were some subjects who gave no detail describing positive disintegration-type episodes but who still appeared to fit a high emotional level.

In Part 2, I address Introduction to Dabrowski’s Levels II and III from the Study of Highly Gifted Adults.

*A free link to my entire dissertation: https://dabrowskicenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Ruf1998.pdf

*One of the people who read my dissertation after it was published (Michael Piechowski) asked me why I assigned specific subjects the developmental levels that he thought were higher than I saw them to be. I told him that I was aware that I wasn’t yet self-actualized at the time. I told him it wasn’t likely I would be good at recognizing some higher level development because my own development wasn’t in the higher ranges, in my opinion. Part of self-actualizing is feeling a universal love and caring, not being bitter or angry (or complaining all the time) and feeling a calmness and generosity toward making the world a better place. I knew I wasn’t there yet, but I did want to be. He hadn’t thought of that (maybe I seemed wise; I don’t know), but then he showed some enthusiasm for discussing those cases. After all, it was his life’s work. I’d invited him to be on my committee from another institution but I hadn’t heard back from him at the time.

[1] Ambrose, D., Cross, T. (2009) (Eds.) Morality, ethics, and gifted minds. Springer Publishing. Full PDF of the Ambrose and Cross Morality, Ethics and Gifted Minds book is here. My contribution is in Chapter 20. http://ndl.ethernet.edu.et/bitstream/123456789/30241/1/26.Don%20Ambrose.pdf

[2] Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development (Vol. 2). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row. Lefton, L. A. (1994). Psychology (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allen & Bacon.

[3] Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Ballentine Books. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

[4] Nelson, K. C. (1989). Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration. Advanced development: A Journal on Adult Giftedness, 1, 1–14. My favorite explanation. ~DR

More Writings and information About Dr. Ruf

The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us (2023)

and Keys to Successfully Parenting Gifted Children (2022, 2023)

Professional Website: www.FiveLevelsofGifted.com

Dr. Ruf is available for the following services. Click for details or to schedule:

One-Hour Test Interpretation

Gifted Child Test Interpretation & Guidance (and for Adults, too)

20-Minute Consultation

45-Minute Consultation

One-Hour Consultation

Podcast Interview

Substack: Gifted Through the Lifespan

Medium

https://deborahruf.medium.com/

Gifted Through the Lifespan is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support Dr. Ruf’s work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

References and Selected Other Resources

Ambrose, D., Cross, T. (2009) (Eds.) Morality, ethics, and gifted minds. Springer Publishing. https://a.co/d/gCzFbPx

Boehm, L. (1962). The development of conscience: A comparison of American children of different mental and socioeconomic levels. Child Development, 33, 575–590.

Colby, A., and Kohlberg, L. (1987). The measurement of moral judgment: Vol. I, Theoretical foundations and research validation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth, and crisis. New York: Norton. Falk, R. F., and Miller, N. B. (1998). The reflexive self: A sociological perspective. Roeper Review, 20(3), 150–153.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Flexner, S. B. (Ed.). (1987). The random house dictionary of the English language (2nd ed.). New York: Random House.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Greenspon, T. (1998). The gifted self: Its role in development and emotional health. Roeper Review, 20(3), 162–167.

Gross, M. U. M. (1993). Exceptionally gifted children. London: Routledge. Hall, E. G., and Hansen, J. B. (1997).

Self-actualizing men and women: A comparison study. Roeper Review, 20(1), 22–27.

Janos, P. M., Robinson, N. M., and Lunneborg, C. E. (1989). Markedly early entrance to college: A multi-year comparative study of academic performance and psychological adjustment. Journal of Higher Education, 60, 496–518.

Josselson, R. (1991). Finding herself: Pathways to identity development in women. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development (Vol. 2). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row. Lefton, L. A. (1994). Psychology (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allen & Bacon.

Levinson, D. J. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Ballentine Books. Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

McGeorge, C. (1975). The susceptibility to faking of the defining issues test of moral development. Developmental Psychology, 44, 116–122.

Narvaez, D. (1993). High achieving students and moral judgment. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16(3), 268–279.

Nelson, K. C. (1989). Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration. Advanced development: A Journal on Adult Giftedness, 1, 1–14.

Peck, R. F., and Havighurst, R. J. (1960). The psychology of character development. New York: Wiley.

Piechowski, M. M. (1975). A theoretical and empirical approach to the study of development. Genetic Psychology Monographs, 92, 231–297.

Piechowski, M. M. (1989). Developmental potential and the growth of self. In J. L. VanTassel Baska and P. Olszewski-Kubilius (Eds.), Patterns of influence on gifted learners: The home, the school, and the self (pp. 87–101). New York: Teachers College Press.

Piechowski, M. M., and Silverman, L. K. (1993, July). Dabrowski’s levels of emotional development. Paper presented at the Lake Geneva Dabrowski Conference, Geneva, WI.

Rest, J. R. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Rest, J. R., Turiel, E., and Kohlberg, L. (1969). Level of moral judgment as determinant of preference and comprehension made by others. Journal of Personality, 37, 225–252.

Rest, J. R. (1986). Defining issues test, manual. Minneapolis: Center for Ethical Development, University of Minnesota.

Rest, J. R. and Narvaez, D. (1994) (Eds.) Moral development in the professions. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ruf, D. L. (2009). Self-actualization and morality of the gifted: Environmental, familial, and personal factors. In, Ambrose, D., Cross, T. (2009) (Eds.) Morality, ethics, and gifted minds, pp. 277–283. Springer Publishing.

Ruf, D. L. (1998). Environmental, familial, and personal factors that affect the self-actualization of highly gifted adults: Case studies. Unpublished dissertation: University of Minnesota.

Scheidel, D., and Marcia, J. (1985). Ego integrity, intimacy, sex role orientation, and gender. Developmental Psychology, 21, 149–160.

Sheehy, G. (1974). Passages: Predictable crises of adult life. New York: E. P. Dutton.

Silverman, L. K. and Kearney K. (1989). Parents of the extraordinarily gifted. In advanced development: A journal on adult giftedness, 1(1), 41–56.

Silverman, L. K. (Ed.) (1993). Counseling the gifted & talented. Denver, CO: Love.

Strauss, W., and Howe, N. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s future. New York: William Morrow.

Turner, J.S., and Helms, D. (1986). Contemporary adulthood (4th ed.). Chicago, IL: Harcourt College Publishers.

Walker, L., deVries, B., and Bichard, S. L. (1984). The hierarchical nature of stages of moral development. Developmental Psychology, 20, 960–966.

Woolfolk, A. E. (1995). Educational psychology (6th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.