Celebrating a Lifetime of Resilience, Scholarship, and Influence

Dr. Michael M. Piechowski at 90

Note: This is a long post. If it’s truncated in your email inbox, click here to view it in a browser.

All year, I’ve wondered how to best honor my friend and mentor, Dr. Michael M. Piechowski, for his 90th birthday. One way to do it is by celebrating his work here on Substack. In this post, I will briefly cover Michael’s early years and wrap up with the chapter that introduced overexcitabilities to gifted education in 1979. I’ll be sharing posts about his work throughout December.

Michael was born on December 2, 1933, in Poznań, Poland, and was the middle child of three boys. In September 1939, as Michael neared his sixth birthday, Poland was thrust into the throes of war, and occupied by Germany. This brought immediate and profound changes to his life, including his education.

When he started school, it was in an area of Poland where speaking Polish was now forbidden, and he was suddenly expected to speak German. His parents moved their children more than once during the war to keep them safe, including to the mountains near Zakopane, a place that is still dear to Michael.

He didn’t get to finish fifth grade because war action interfered—the front was approaching, and school couldn’t continue. We talked about his early education during one of my trips to Wisconsin. From my notes:

“He worked with a tutor who caught him up on grades 6-8 after the war. They moved back to Poznań in the middle of his junior year, and he graduated from high school in 1951. He got his master’s degree in 1956, and he lived with his parents during his years at the university. He laughed when I asked him where he lived—he said housing was scarce [so much of it was destroyed during the war] and only students from other areas would have lived in a dorm. He said his family shared an apartment with another family for a long time.” (Journal entry, September 16, 2020)

Michael attended the University of Poznań, which became Adam Mickiewicz University in 1955, a year before he graduated with a Master of Science degree in plant physiology in 1956.1

In May 1958, he left Poland and accepted an assistantship to study in Belgium. From there, he wrote to professors in the US, hoping someone would take him as a graduate student. In 1959, he came to the United States and started a doctoral program at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He transferred to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and completed his PhD in molecular biology in 1965.

Dr. Howard Temin was on Michael’s doctoral committee. Temin received a Nobel Prize in 1975 for showing that “certain tumor viruses carried the enzymatic ability to reverse the flow of information from RNA back to DNA using reverse transcriptase.”

Michael's journey took an unexpected turn, and he had to leave the United States due to visa constraints. He considered multiple English-speaking countries as options and ended up in Canada at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Shortly after arriving in Edmonton in January 1967, he met Dr. Kazimierz Dąbrowski. He shared the story of meeting Dąbrowski in podcast episode 48.

First Years Working with TPD

The first project Michael and Dąbrowski worked on together was writing chapters for the book that became Mental Growth Through Positive Disintegration. Two chapters were adapted and translated into French and published in 1968 and 1969 in Annales Médico-Psychologiques.

The paper from 1968 became Chapter IV in Mental Growth, titled “The Inner Psychic Milieu.” Even though Michael wasn’t listed as a co-author in the paper, they were listed as co-authors in the book. The 1969 paper became Chapter V in Mental Growth, “Higher Emotions and the Objectivity of Valuation.”

What is the inner psychic milieu? From Mental Growth:

“Inner psychic milieu is a complex of mental dynamisms characteristic for a given individual. The dynamisms operate on one level (unilevel interaction) or on several levels (multilevel interaction). The dynamisms interact either synergistically or antagonistically (inner conflict).” (p. 62)

They described four types of inner psychic milieu: primitive, disintegrated, integrated, and pathological. Which dynamisms are present in an inner psychic milieu that’s undergoing disintegration?

“We encounter here all the essential dynamisms of the inner milieu, to be described later. We shall mention here: astonishment with oneself, anxiety, feelings of inferiority towards oneself, feelings of shame and guilt, the third factor, disposing and directing center on a high level, personality ideal, etc. This type of inner psychic milieu is found in individuals undergoing the process of positive disintegration, and it is fundamental for positive development of the human individual.” (p. 63)

In Chapter V, they wrote about the possibility of establishing an objective hierarchy of values and distinguishing the levels of development of emotional and instinctive functions. In the section titled “The Empirical Basis of Valuation,” they wrote:

“In order to establish a hierarchy of values we must first examine developmental transformations of emotional functions. We shall show on the examples of self-preservation instinct, syntony and empathy, sexual instinct and attitude towards death how the levels of these functions can be distinguished.” (p. 93)

In Chapter V, they also described “Levels of Neuroses of Indicators of Levels of Development”:

“We consider metal disturbances, neuroses, and the like, to be—from the developmental point of view—clearly positive, partially positive, or negative. Inner mental development occurs through crises and periods of mental disturbance. Every level of development has a corresponding level of mental disturbances. It is our purpose here to correlate different levels of developmental factors with different kinds and levels of mental disturbances.” (p. 99)

Here, they talked about a range of psychoneurotic and psychotic disorders as representing different levels of developmental processes, including unilevel and multilevel disintegrations.

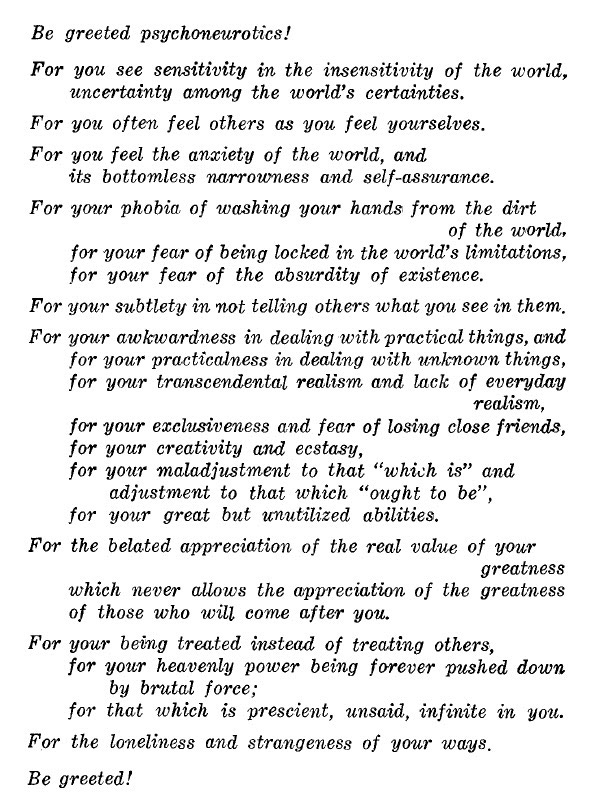

One piece of Michael’s translation work that will be familiar to many readers is the “Psychoneurotics’ Manifesto,”2 also known as the “Be Greeted” poem. This image is from Dąbrowski’s 1972 book Psychoneurosis is Not an Illness.

Although uncredited in the book, Michael told me Dąbrowski asked him to translate the Polish version3 of the poem into English.

Michael later produced a second translation because he wasn’t satisfied with the first one. He used the poem from the French edition of Mental Growth,4 published in 1972, for the second translation, which begins, “Hail to you, psychoneurotics!”5

After Mental Growth, Michael continued working with Dąbrowski on Psychoneurosis is Not an Illness and the Multilevelness Research Project, which culminated in a two-volume set of books called Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions. The books were first published in 1977 as Theory of Levels of Emotional Development, Vols. 1 & 2.

A Second Doctorate

In 1970, Michael left Edmonton and returned to the University of Wisconsin, Madison, for a second Ph.D., this time in counseling and guidance. He wrote about their work together in his 2008 chapter “Discovering Dabrowski’s Theory”:

“The years 1970 and 1971 were spent working together on his book Psychoneurosis Is Not an Illness (1972). Pages with clarifications, elaborations, inclusion of new clinical examples, and successive revisions grew to a stack one foot high. As Dabrowski tended to grossly underestimate the amount of work needed, I was tempted to send my stack of pages to him as concrete evidence of the amount of labor involved. At one time, I told him that I was sure it would have been easier to be his patient than to work with him. He agreed. Still, his sense of urgency about the work made the whole atmosphere around him charged with excitement.”

Michael published his first solo paper about the theory in 1974 in the journal Counseling and Values. He used cases from Psychoneurosis is Not an Illness to show the difference between the unilevel and multilevel processes. This excerpt captures well Michael’s preference for using case material to illuminate concepts rather than definitions:

“A definition of a concept, no matter how good and precise, does not prepare one to apply the concept because the knowledge of the definition still lacks the contexts and situation which give life and meaning to that concept. For instance, knowing the definition of the gene does not tell one the concept of the gene. One has to take a course in genetics and do some experiments before the concept of the gene acquires meaning. We know a concept when we can apply it in all possible meaningful contexts. We never know a concept fully because we never exhaust all possible meaningful contexts. The concept of concept requires us to be open to new possibilities and new contexts. Clearly, concept is fundamentally different from term which only describes and names. The common difficulty with the theory of positive disintegration, as in every other case, is in not realizing that the meaning of its concepts cannot be learned from their definitions alone. This difficulty is amplified by the fact that the theory is conceptually very rich. In consequence the theory presents an uncommon challenge.” (Piechowski, 1974)

This paper, “Two Developmental Concepts: Multilevelness and Developmental Potential,” names the two foundations of the theory of positive disintegration. It gives examples from Dąbrowski’s cases to bring the concepts to life.

Based on the research work he did on the Multilevelness Project, Michael produced a monograph published in 1975 called A Theoretical and Empirical Approach to the Study of Development. The most important thing about the monograph is that it includes the first empirical tests of the theory. As I’ve mentioned in a recent post about NAGC, the research done by Michael and Dąbrowski has been largely ignored or forgotten in gifted education. In order to refresh our memories, here’s a description of the empirical tests from Piechowski (2008):

“The detailed, atomistic content analysis of the autobiographies and Verbal Stimuli made possible three empirical tests of Dabrowski’s theory. The possibility of such tests did not present itself until after the ratings were done. The dynamism ratings from each subject did form a cluster. Each cluster corresponded to part of the overall spectrum of dynamisms from Level II to V. The material from each subject provided a developmental cross-section. These cross-sections overlapped and together reproduced the complete spectrum. This made one empirical test of the theory.

The second empirical test was provided by checking the constancy of DP. DP was calculated by adding the frequencies of dynamisms (d) and overexcitabilities (oe): DP = d + oe. The relative frequencies varied, but the sum was expected to remain constant. When the material from a chronologically written autobiography was divided into two halves—early and later portions of life—the DP value was very close for the two halves. However, between the first and the second half, the balance of dynamisms and overexcitabilities changed dramatically.

The third empirical test compared clinical intuitive estimates of DP for each subject made by Dabrowski with the calculated values obtained from the content analysis. These two sets of values showed reasonable agreement. The close three-way agreement between the level index obtained from the neurological examination with the indices obtained from autobiography and Verbal Stimuli serves as an additional test.

Another test of internal consistency was the computation of the value for developmental potential from DP = d + oe [as above], where d is the frequency of expressions of dynamisms in a subject’s material and oe is the frequency of expressions of overexcitability. The material from each subject was divided into two halves. The DP was then computed from each half independently. The correlation between these 14 pairs of values was .94.”

Michael submitted this work as his dissertation in 1973 and was told it wouldn’t be sufficient. His doctoral committee asked him to compare Dąbrowski’s theory with other theories of counseling and to discuss the implications for counseling. That work became his second dissertation, Formless Forms: The Conceptual Structure of Theories of Counseling and Psychotherapy. Here’s a description of his process:

“What follows is a more or less sequential narrative of my search for criteria of comparison and evaluation of the theoretical framework of a number of approaches to counseling and psychotherapy. Four criteria presented themselves: (1) the form of concepts employed, (2) the actual meaning of notions of structure and function as employed in a given theory, (3) the incorporation or exclusion of general principles from the framework of a theory, and (4) reference to the organism’s equipment, i.e., to what the organism has a capacity for rather than how its behavior varies over different situations (this criterion is called “properties of the organism”). A fifth criterion, of particular significance to the application of theories of human nature, concerns the value structure each theory is fitted to recognize. These five criteria enable one to compare the theories in respect to their construction rather than manifest content.” (Piechowski, 1975)

The theories of counseling and psychotherapy came from Corsini’s textbook Current Psychotherapies (1973) and included:

“Psychoanalysis, Adlerian psychotherapy, analytical psychotherapy (Jung), client-centered therapy, rational-emotive therapy, behavior therapy, reality therapy, Gestalt therapy, experiential psychotherapy (Gendlin), encounter (Schutz), transactional analysis, and eclectic psychotherapy.”

Formless Forms is a great read, and I highly recommend checking it out. He has called that work “the peak of his intellectual life.”

I’ve had the pleasure of reading the three notebooks Michael saved from 1975 with his notes from studying the philosophy of science and the twelve theories he included. They are full of gems, such as this excerpt from very early in the process:

In case you can’t read his handwriting, the above image states: “Ignorant remarks: they show that those who make them have no idea how a scientist lives his science.”

One more example, this time about unilevel disintegration (UD) and differentiation:

“In unilevel disintegration it is of crucial importance how differentiated—in each individual case that is studied—are the ambivalences and ambitendencies. The more strongly defined they are in terms of emotional tension, of experienced conflict, the better is the prognosis for multilevel development. Otherwise there is an “adjustment” to UD, partial integration, or search for level I leadership, or the end.”

Here’s a photo of Michael from this period of his life. The map on the wall behind him is of the Grand Tetons.

Early Career in Academia, Again

Michael completed his second Ph.D. in 1975 and went to work as a visiting professor at the University of Illinois. I suggest listening to episode 35 with his former student, Dr. Patty Gatto-Walden, for her recollection of him during those years.

Moving on to Michael's next major work in the 1970s, we come to another monograph, published in 1978: Self-Actualization as a Developmental Structure: A Profile of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. Again, from his 2008 chapter:

“Using the Saint-Exupéry’s material, I set out to identify the characteristics of self-actualization. First, I compiled a list of descriptors of self-actualization from Maslow’s chapter in Motivation and Personality (Maslow, 1970), in which he delineated 16 characteristics of self-actualizing people. Then I tried to identify these characteristics in each of the 113 units from Saint-Exupéry. The task of working out the intersection of the 16 characteristics of self-actualization with the 30 dynamisms of Dabrowski’s theory was extraordinarily tedious, yet deeply satisfying. Of Level III, only two dynamisms, hierarchization and positive maladjustment, were strongly represented in Saint-Exupéry’s profile, but of Level IV, all but two were present. There were no traces of Level II. This, to me, convincingly demonstrated that when Maslow described self-actualizing people, he was looking at the same kind of people on whom Dabrowski had been formulating his idea of Level IV.”6

Rounding out the early major work from Michael in the 1970s is the chapter that introduced the overexcitabilities to gifted education in 1979, “Developmental Potential.” It was published in a book called New Voices in Counseling the Gifted, edited by two of his friends from graduate school, Drs. Nick Colangelo and Ron Zaffrann.

The abstract reads:

“Today's concept of giftedness has been broadened to include considerably more than academic capability as measured by I.Q. tests, yet, the call for broader conceptualization has essentially resulted in further test orientation. There is a need for a model that would enable one to conceptualize giftedness in terms other than testable skills. This paper presents a psychological model of giftedness that accounts for intellective and non-intellective dimensions, especially those of imagination and feeling. The model rests on the concept of developmental potential taken from a theory of human development. The value of this concept lies in that it gives readily identifiable components: special talents and abilities and five forms of psychic overexcitability: psychomotor, sensual, intellectual, imaginational, and emotional. Specific examples of expressions of overexcitability identified in case data with gifted are given.”

Michael introduced the idea that the OEs might be a way to identify giftedness in 1979, which led to the work in the 1980s and 1990s to test that hypothesis. Now, we know that although OE isn’t a reliable way to identify giftedness, it is commonly experienced by gifted individuals. The broader theory of positive disintegration is a non-pathologizing framework for understanding intense experiences, including giftedness, as well as other types of neurodivergence.

You can expect multiple posts with excerpts from Michael’s work over the next month, which I will discuss by decade.

Michael’s master’s thesis is available on ResearchGate.

Dr. Dexter Amend mentioned in his 2008 chapter on “Creativity in Dabrowski and the Theory of Positive Disintegration” that the Psychoneurotics’ Manifesto was used in the Second International Congress on Positive Disintegration brochure in 1972.

This is page 22 of Myśli i Aforyzmy Egzystencjalne [Existential Thoughts and Aphorisms] by Paweł Cienin (Dąbrowski’s pen name). It’s #82, beginning with Bądźcie pozdrowieni psychoneurotycy!

Dabrowski, K. (with Kawczak, A., & Piechowski, M. M.). (1972). La croissance mentale par desintegration positive. Les Editions Saint-Yves.

I’ve linked to the version published in Piechowski (2015), A Reply to Mendaglio & Tillier.

Dąbrowski removed his name as the second author of this paper. Read the 2008 chapter for more on this issue and about Michael’s early years working with the theory.