My Experience Being a Student

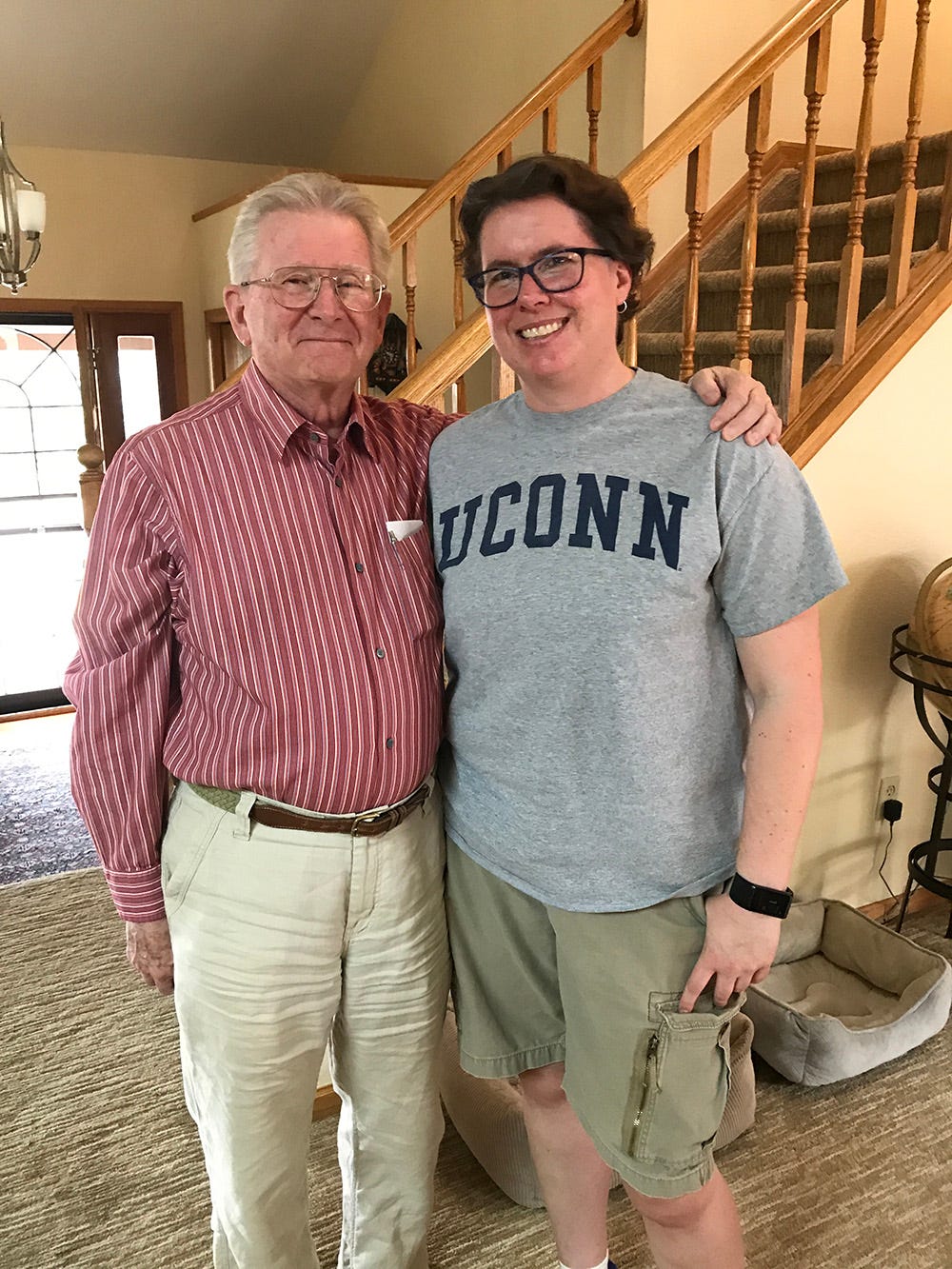

Enjoying the process on this journey with Michael

It’s my last full day in Wisconsin, and I’m glad to share some reflections from this visit with Michael. Tomorrow morning, I’ll start driving back to Colorado and processing the moments I’ve had here.

Whatever you imagine the experience of being Michael’s student is like, I’m sure the reality is different. It’s been wonderful and also very challenging. The trips to visit him here in Madison have all been special, even though some were more difficult than others.

In episode 35, with his friend Dr. Patty Gatto-Walden, I said that I’ve felt like I’m part of Michael’s family. I said that to her because Patty is also part of Michael’s family, and I have loved including guests who are close to him.

Next week is the second anniversary of the podcast, and I’ve been reflecting on our guests and episodes. We choose guests not because they’re popular or well-known, although sometimes they are popular and well-known. We choose our guests because we think they have a message worth sharing, and that message connects with our work on Positive Disintegration.

Before discovering Dąbrowski’s theory, I had always tried to come up with my own theory. I’ve never been the kind of person who was looking for a teacher. I grew up always searching for alternate routes around the way things were, and that often meant doing the opposite of what I was told.

When I started actively searching for a mentor in 2015, I imagined finding someone who would guide me through the early career process. I thought I would become a professor of psychology, but nothing in the field had inspired me.

I finally found inspiration and passion in the theory of positive disintegration, but it came through Michael’s work in gifted education. It also didn’t happen immediately. At first, I strongly resisted Michael’s work. During the early days of the first autoethnographic work, I searched for intensity, especially emotional intensity, along with giftedness, and his work came up constantly. But I resisted buying his book Mellow Out.

I recognized an alternative to the pathology paradigm in Michael's work, but as I’ve said elsewhere, I wasn’t interested in a different lens. I had accepted myself as mentally ill and wasn’t interested in rethinking that view. I thought my work was to live as an example of someone who had succeeded despite mental illness. I fully expected to continue taking medication for the rest of my life for bipolar disorder.

Once I was talking with people in the gifted field, they all seemed to be pointing me in Michael’s direction. Had I read about the overexcitabilities? Had I heard about positive disintegration?

Yes, I had. And I thought I was done with it, but it was only the beginning.

Finally, I went to a workshop on coding the open-ended Overexcitability Questionnaire (OEQ) in November 2015. The workshop was led by Drs. R. Frank Falk and Nancy Miller, who identified themselves as social psychologists. They happened to be a married couple in their 70s, and they’d been working with the OEQ since 1980.

Hearing Frank and Nancy talk about Michael made all the difference for me. I’d read Living with Intensity and some of Michael’s other work. They talked about Michael as a real scholar. There was a deep respect in their voices that caught my attention.

I finally purchased Mellow Out, but I still didn’t read it. We were in the process of selling our house and moving into another one, which required all of my effort and attention for a few months.

Nancy was the editor of Advanced Development Journal, and she encouraged me to write a paper about my autoethnographic work. The deadline for the journal’s call for proposals was January 31, 2016. Even though we were preparing to move, and my maternal grandmother died, I wrote a paper. I called it “Embracing the Challenge of Twice-Exceptionality.”

Right before the OEQ workshop, I had joined a Facebook group about Dąbrowski’s theory and felt appalled by the divisiveness of the community. It made me reluctant to engage in any way, and in retrospect, I realize that this is why I had so much resistance to pursuing the theory in depth, especially Michael’s work. It felt unsafe to my nervous system, and I kept a distance until that workshop with Nancy and Frank. Meeting them, along with Dr. Linda Silverman and Mary Krayer, led me to feel a connection with the gifted community and the theory.

In my first Substack post about Michael, I talked about how he wrote to me about the paper I’d submitted to Advanced Development because it turned out he was the associate editor. It never occurred to me that he might be the one who reached out with feedback and a decision. I assumed it would be Nancy because I already had a relationship with her.

When Michael wrote to me, we were still moving into our new house, and things were chaotic. But it stopped me in my tracks to get his email. It shocked me but in the best kind of way.

Understand that I had never received feedback like I got from Michael about the paper I submitted. It wasn’t even fully completed because I’d been too overwhelmed to write a proper paper in January. I did the best I could with the material I had from the autoethnography.

I hadn’t cited Michael’s work once in the paper, and I felt embarrassed because it was an oversight on my part. I’d mentioned his name on one of my slides at TQR 2015, and his work had definitely informed my thinking.

His questions for me were so good. I could hardly read his feedback because it felt overwhelming. I’m the kind of person who has to read a message like his by slowly processing it. I can’t take it all in right away. It’s like dipping my toe into the water but with words in emails. This is true with any message that feels charged emotionally, whether the sender intends it to be that way or not.

So, I printed it out and left it on my desk. I looked at it repeatedly until I’d taken it in, and then I wrote back to him with thanks. The feeling before hitting send was cold panic. I felt fear about writing to him, which was unusual. I expected him to be very different than he actually is, which is interesting to admit.

I knew he had to be pretty old, and it turned out that he was 82 in spring 2016. I knew he was from Poznań, Poland, and he’d worked with Dąbrowski. I had no idea what he was like as a person.

My other reaction to his message was to tell Nancy I wanted to work with her on the paper. Or perhaps Frank. Michael felt intimidating and unapproachable to me at first, but Nancy said he was the perfect person to work with me.

I decided to take his work seriously and began reading it carefully. I started with what I’d already read (see Interesting Quotes, Vol. 2), and kept going. Now that I was paying attention, I felt ready to engage with him.

In May 2016, I wrote to him:

“My first question: if you have the time and interest, could you please help me cut a path? I think that I know what I’m meant to do—and can articulate it—but not how to make it a reality. This has been perhaps the biggest obstacle I’ve faced in the past few years. People assume that I know how to work—that I have experience in the professional world—but I don’t. I was on Social Security Disability for over a decade and have been in school for ages. I feel confident that I can make a difference, but unless someone helps me with the details, I will continue to struggle in the execution of making it happen.

To help me cut a path, you’d need to know where I want to go. You already have an idea of where I am and where I’ve been.” (Email to Michael, May 2016)

I know now that Michael had no idea what I was asking for when I asked him to help me cut a path. He didn’t really have much of an idea of where I was at that time.

To my mind, I was asking him to be my mentor. I wanted him to guide me, teach me how to be a scholar, and help me become a professional. It was a huge ask, and I didn’t know him or anything about him. I could tell from his work and the few things he’d written to me that this was what had to happen.

The next months or years were spent studying his work and telling him about my past. The word count numbers from our emails are astonishing. The 2016 Dąbrowski Congress is when I started writing to him regularly.

There was never a time when Michael said, “Yes, I’ll be your mentor and help guide you on this path.” But he was available for my questions, and I could share my writing. There were two revisions of the paper he helped with, and it became The Primary Importance of the Inner Experience of Giftedness.

Like many people who come to the theory, I thought I was at a higher level than I actually was at first. In my case, I could see how far I’d come and that I had been through many transformations that could be understood as positive disintegrations.

I’ve never met anyone else who has been able to hear what I have to say about my past and who I am and respond to it the way Michael can. The mirroring with him has been essential for my personal growth. He is always helping me find my way, but it’s never by pointing me in any particular direction.

In early 2021, I started reading Mastery by Robert Greene and recognized what I’ve gone through while learning with Michael. I’m realizing it’s time to do an Interesting Quotes post with excerpts from Mastery. Here’s one we shared on the Dąbrowski Center’s Instagram account:

This excerpt from Greene resonates because the process of studying the theory and learning how to share this work has been about learning who I really am and reconnecting with my inner authority and power.

With Michael, his teaching and mentorship come from how he walks his talk, as Emma would say. He’s authentic and doesn’t say things he doesn’t mean.

Because of the way my mental processes work, I brought him into my head early on. It’s great that I was so honest with him about it, but that seemed necessary and part of getting to know him.

From an email to Michael:

“It seems incredible that it takes so little for me to build a representation of someone in my head that I can interact with. That's what had to happen. Of course, now I can recognize other times in which this sort of thing has happened, so I know that however you really are—for real, in person—will only become a part of that representation and make it more real when I meet you.” (Email, August 28, 2016)

He never asked to have me in his life, and the first couple of years weren’t easy. By bringing him into my head, I was making a commitment to this work. Before that, I’d been on the fence.

Prior to knowing Michael, I’d always had the experience of an imaginal world that ran parallel or simultaneously with concrete reality. It’s part of why I thought I was mentally ill, which is important to remember.

Once I was talking with Michael in my mind, it changed the experience of the imaginal world, and that process no longer works the same way. There are aspects of getting to know him that I can’t explain. I can only describe it by sharing the words from my journals or emails that seem to capture the essence of the experience.

The dynamisms were in action with Michael. The imaginal space became a subject-object process for me where I could see myself and my actions objectively while also deepening my understanding of others as subjects. It helped me change and do better not only with Michael but in all of my close relationships.

I recognized early on that I needed to be very careful with Michael because I didn’t want to impose on him, and I wanted to let him lead. I knew I could be overwhelming and exhausting—“too much”—and I wanted to be a welcome part of his life, not a burden.

I knew I had to aim higher than simply being tolerable for him. I wanted to be a blessing in Michael’s life, and striving for that as his student was easy.

There were points when he seemed to become the mentor I needed him to be, although I realized later that it wasn’t necessarily intentional on his part.

The Reluctant Mentor

At the very time when I committed to studying the theory and was on the path to doing the work I do now, overexcitability was under fire in gifted ed. It didn’t take long to realize that Michael had no idea of the magnitude of this problem because he wasn’t on social media.

Along with this issue, I saw that choosing to study this theory came with risks, and I decided to proceed despite the red flags in the Dąbrowski community.

Making the first attempts to write about Michael in 2021, I called him The Reluctant Mentor, which I planned to call the book I’ve been working on. Someday, there will be a first book about Michael, and perhaps that will still be the title.

From Mastery:

“To reach mastery requires some toughness and a constant connection to reality. As an apprentice, it can be hard for us to challenge ourselves on our own in the proper way, and to get a clear sense of our own weaknesses. The times we live in make this even harder. Developing discipline through challenging situations and perhaps suffering along the way are no longer values that are promoted in our culture.” Robert Greene

When people spend time around me and Michael, they can see we’re close. I think that leaves the impression that we have a dynamic like we’re family, but I see it as the teacher/student bond. We have been developmental challenges with each other, and it’s not one-sided. Michael has been very knowable and accessible with me, and I can see that I have an influence on him, too.

He’s been extraordinarily open with me and has given me access to his life and loved ones. He’s helped me with my dissertation and assisted with papers and numerous conference presentations. We wrote a chapter together and worked together at Yunasa five times. So, we’ve become colleagues and friends.

During the early years when I was here visiting Michael in Madison, it felt like I was torturing him with my presence. Because I’d brought him into my head, I felt an early familiarity that wasn’t the same for him. I trusted my intuition and did my best to ask him for feedback and to be a low-impact guest when I visited.

Michael is a model of how to be nonjudgmental, compassionate, and kind. He also has a brilliant mind and emotional sensitivity. He’s empathic and warm but also private and reserved. He can be prickly, and I even gave him a little stuffed porcupine last year in honor of this aspect of him. He never speaks ill of anyone and doesn’t gossip. He seems to find the spark of good in everyone and everything.

The beauty of this process of becoming Michael’s student has been the joy of deepening the connection with him and his work. I’m constantly seeing how I’ve grown up while knowing Michael, personally and professionally.

The document with excerpts I’ve coded from my journals with “The Reluctant Mentor” is 63 pages in Word. They’re all excerpts that show the mentor relationship, but also more than that.

Now that I’m doing the podcast with Emma and my work is out in the world as it is, I can see what a wonderful mentor Michael has been for me. He has modeled qualities that I try to bring to my work, like humility, integrity, and honesty. I’ve learned so much from him in so many ways, but I’ve also learned from studying his work.

Being Michael’s Student

So, what is the experience of being a student? It has sometimes felt lonely. I don’t know anyone else who has a mentor relationship like this, and Michael doesn’t always know how to deal with me.

“It must have been strange for Michael that I went through all of this with him. It seems like he’s been very careful not to influence my development. It’s an interesting thing to realize. I’ve loved every minute of this process with him. Even the difficult moments… It was a serious adjustment in both of our lives. I know that I was meant to learn with Michael and become his student… He’s always ready to challenge me and give me a hard time. It’s exactly what I’ve always needed. He’s been my guide.” (Journal entry, February 2021)

When I see what other people are doing in their work, I know my path is different. I’m not an academic, and I didn’t end up becoming a professor. I think Michael is probably disappointed by what I’m doing right now. I don’t think he understands why I’ve chosen to share my writing on Substack. But I’ve learned to trust myself and do the work that feels right for me.

I’ve known since I was young that I was meant to help people and be of service. But this mission didn’t come with an instruction manual. Meeting Michael was the key to finding myself and my direction.

In the interviews I’ve done with Michael’s people—his friends, colleagues, and loved ones—I’ve asked them to talk about his impact on their lives. I’ve tried to answer that question for myself multiple times. Here’s what I said in March 2022:

“What impact has Michael had on my life? First of all, several things that I was quite certain about when I met him turned out not to be so true, or straightforward. Beyond that, he introduced me to many people and ideas that have led to transformations in me. He has helped me become a different person—I’m stronger now, and I have faith in myself and my work. I have a clear direction. Somehow Michael has helped me integrate my realities, and I no longer experience the imaginal world. He provided learning opportunities for me in our relationship that have led to the emergence of dynamisms. Then there are the more external things—the doors he has opened for me in the field. The chance to work with him in multiple ways. The gift of his mentorship and his friendship.”

Visiting him this week, in October 2023, I’ve been aware that this is the last time I’ll see him before he turns 90. There’s a 40-year age difference between us. I’ve been trying to adjust to turning 50 this year without complaining about feeling old to Michael, but sometimes I forget. He’s understanding and remembers what it was like to be 50.

Michael’s 90th birthday is coming in early December, and I plan to honor him this fall by sharing posts about his life and work here on Substack. I’ll be talking about him during my session at the National Association for Gifted Children conference on November 10, 2023, at 10:30 am ET.

I’d like to return here to help celebrate his birthday in December, but he’s discouraging me from spending money on flying to Madison. We have different priorities. As someone who can be described as emotional and an experience collector, I would love to be here. But perhaps he’s right, and I should take a lesson from his modesty and frugality.

Studying the theory with Michael, as well as his life, has been challenging but also extremely rewarding. When I say that I’m Michael’s student, I don’t mean it like being a graduate student. The lessons I’ve been learning, and the transformations I’ve gone through have been more spiritual than academic.

Soon, I’ll be headed home and processing the experience of spending time with him over the past week. I’m grateful for the gift of his energy and attention, and I’m excited to keep sharing what I’ve learned with you.

What a post to read, what inspiration! Thank you Chris. I am so grateful that you are sharing your writing on substack. Just the part about you moving house and dealing with the passing of a family member - I am dealing with building and family issues that are, to my mind, 'distracting' me from the huge pile of stuff I have piled up in my head to be sorted out! Sigh. Breathe. There is time, and there is an aim for something I can't let go of even if I wanted to. I have saved the reading material in this post and will read. thanks again 🙏🙌🍂🔥

Again something wonderful to read!

I also want to do something in the field of gifted education. I’m 43 and finishing my undergrad in data science. Still doesn’t know what is the right career choice for me.

I want to understand more about TPD and giftedness.

I’m glad that I subscribed to this sub stack!!