Guest Post: Gifted Children and Their Personality Types

How They Do or Don’t Fit Into School (and some other ways of their “being” that can cause problems)

Welcome to our first guest post! Thank you, Deborah Ruf for sharing your work with our subscribers. Click here to listen to Episode 50 with Dr. Ruf on Positive Disintegration.

Visit Dr. Ruf’s Substack, Gifted Through the Lifespan

Both gifted child and parent personalities matter hugely for how they see the school years. If the parents’ expectations fit those of their child, things go a lot better no matter what the schools do.

When I wrote “Smart Kids, Personality Types & How They Adapt or Not to School” in 2004 I was still learning how personality styles might affect the educational outcomes of different gifted children. Twenty years later, I have a much clearer picture to share with readers.

Why Did I Look Into This?

Personality typing has been used for years in various personal and career counseling situations because it helps people understand their own motivations and needs compared to those of others with whom they live and work. When we fit an environment, be it work, play, our families, or school, things tend to go better.

As a private consultant and specialist in high intelligence, my primary interest was in gifted children. It was later that my interest in their parents grew. I read in my early studies of gifted children that altruism and empathy were more prevalent and more developed in highly intelligent children. Many researchers wrote that some children, especially intellectually gifted children and adolescents, manifest both sensitivity and concern for others quite early in their lives as compared to non-gifted peers. But does one have to exhibit caring behaviors and altruism to be considered gifted?

A significant aspect of my personal experience, i.e., rearing three highly gifted sons who did not show high degrees of empathy or altruism, led me to consider the possibility that some gifted children and adults are more predisposed to overt “caring” behaviors than others who are equally intelligent. Perhaps a high intellectual level is important, but other personal characteristics are necessary for a caring, altruistic, or empathetic approaches to the needs of others.

I became concerned that some parents and teachers might actually conclude that advanced moral reasoning as described in some of the gifted literature was an essential concurrent factor within those people who were identified as gifted. However, Dąbrowski suggested that a propensity for advanced moral development comes from a base of particular response patterns within the highly intelligent (1964). He also noted that not all highly intelligent people reach the highest levels of such development. Okay; that makes sense and I see those differences in the 65 subjects of my The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us (2023), book (See The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us (2023).) And in my own children (now adults), too.

As I read more in the gifted and personality literature, the most commonly mentioned personality type found among the gifted in most studies was INFP. But, this is not — I repeat — the most common personality type for gifted children or adults!

My own subject pool, the children from client families, was self-selected by parents. I began to suspect that there is probably something about the INFP gifted students that leads parents to take their children to specialists like me. There are also studies that show that certain personality type preferences are drawn to specific careers, so why wouldn’t it also be true that different summer and academic programs for the gifted simply attract some types more than others and would lead to over-concentrations of these types in some studies? I think so!

Research and Practice Can Allow for Individual Differences

During my initial studies of high intelligence, I learned that many people in the field – not just the researchers – assumed that high intelligence and altruism go hand in hand, and that it is part of the moral sensitivity that the gifted share (Dąbrowski, 1964; Gross, 1993; Hollingworth, 1942; Lind, 2000; Lovecky, 1997; Piechowski, 2006; Renzulli, 2002; Silverman, 1993; Terman, 1925; Webb, Meckstroth, & Tolan, 1982).

O’Leary (2005) summarizes this viewpoint as follows:

<<Silverman (1993) suggests “the cognitive complexity and certain personality traits of the gifted create unique experiences and awareness that separate them from others. A central feature of the gifted experience is their moral sensitivity, which is essential to the welfare of the entire society.”>>

O’Leary concludes, “Moral reasoning as an indicator of giftedness and the advanced moral reasoning noted by researchers in the field of gifted education (Gross, 1993; Hollingworth, 1942; Kohlberg, 1984; Silverman, 1993a; Southern, 1993) suggest that those students who demonstrate advanced levels [emphasis my own] need a curriculum and counseling which also address this area of development. Gifted programs — and those working with gifted students — must be aware of the affective traits and needs associated with these children and be aware of the necessity for counseling” (2005, p. 52). And this is great advice and relates to a significant number of gifted students. But not all.

A paper by Piirto (1998) summarizes personality type studies of gifted children and teachers. She points out that various authors have discovered and interpreted school behavior differences that are correlated with personality type preferences (e.g., Jones and Sherman (1979); Murphy, 1992; Myers and McCaulley, 1985; Myers and Myers, 1980), as well as studies of teacher types and interests (Betkouski and Hoffman, 1981; Piirto, 1998).

For example, some studies show the majority classroom teacher type preference is ESFJ (Betkouski and Hoffman (1981), while that of talented students has a higher than the population average for introversion among this group (Piirto, 1998). Uğar Sak (2004) notes that although gifted adolescents demonstrate all personality types as measured by the MBTI, they tend to prefer certain types more than general high school students do. Researchers (Delbridge-Parker & Robinson, 1989; Gallagher, 1990; Hoehn & Bireley, 1988) reported that about 50% or more of the gifted population is introverted compared to the general population; introversion is only preferred by 25% of the general population.

How Personality Typing is Useful in Families with Gifted Children

Beginning in 2000, I administered the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® to all parent clients and Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator for Children® to all children six and older. I continued my practice of having parents complete my own form called Developmental Milestones, a form which included their description of early milestones, reasons they were seeking my help, how others were reacting to their child, and their goals for their child. For readers now, I recommend the online www.personalitypage.com site for accurate results and descriptions at an affordable price.

What Did I Find?

Patterns emerged and by the year 2007 I had data from more than 300 families with gifted children. My public speaking started to include what I was learning from personality typing, which then led to a different pattern of people seeking my help. By 2004, the overwhelming majority of children brought to me for evaluation were P-perceiving: 92%.

P-Perceiving children are less likely to finish their work or stay on task when they find the work to be tedious or uninteresting than are J-Judging students. To me, this suggested that within the student population, there were many gifted children whose personalities allowed them to cooperate in school even when it contributed to their own underachievement, i.e., they could have learned more.

This generally meant that parents and teachers were pleased with the J-Judger students’ behavior and cooperation and such children were seldom brought to specialists for help, guidance, or further evaluation because they were “doing fine” in school.

After I started speaking and writing about how P-Perceiving behavior in gifted children was worrisome to many parents and teachers, and that there are probably many cooperative but under-identified gifted students out there not having their needs met, more smart children who are cooperative in school started finding their ways to my doorstep for evaluation (I worked from home).

Toward the end of my consulting career I saw a slightly higher percentage of J-Judgers than I used to see. And, by the time I wrote the 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up book in 2023, I had personality results for over a thousand families.

Many parents asked if their children’s type preference can change over time. It is generally believed that the S/N types are inborn and highly resistant to change (Piirto, 1998), but the other three dichotomies can change with effort, experience, or current conditions. This would be especially true in children, which is why some people think there is no point in assessing children for type. I find that knowing a child’s current type preference makes it easier to help the child make changes, or it helps teachers and parents know what approaches are likely to be most effective with different children. If their preferences change later, fine; but knowing their current values and viewpoints helps us interpret and deal with current issues now.

The Meanings of the MBTI Letters

The sixteen type preferences revolve around four dichotomous factors of E/I (extroverted/introverted), S/N (sensing/intuition), F/T (feeling/thinking), and J/P (judging/perceiving). Examinees take a written assessment where they respond to items about which of two scenarios they would prefer. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® is for adults and the Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator for Children® is for school-aged youngsters. The results are presented on a continuum for each dichotomy where it is possible to have a strong to slight preference for one quality or another. Here is a brief informal summary of what each letter in the Myers-Briggs means:

E-Extroversion — Energized by being with people, interacting with others. Does not mean talkative; an E can be quiet, even shy.

I-Introversion — Gains energy by being alone; down time generally means “alone time.” Introverts can be talkative and good in groups, but they need “alone time” to recharge.

S-Sensing — Gather information through their five senses; detail-oriented; don’t like theories as much as facts. Like lists, clear directions, time tables. Often very literal, miss nuance, have difficulty generalizing.

N-Intuition — Use intuition and hunches; analytical and theoretical; see the “big picture” and not as interested in the details. Like to create their own plan after they understand a situation; bored by routine; comfortable with some uncertainty.

F-Feeling — Feelings matter, are important; like win-win solutions; generous with praise and affirmations. Sometimes make less than ideal choices in order to please everyone; often hurt when not appreciated; can be quite sensitive to others.

T-Thinking — Practical, direct, expedient. Logic rather than emotion. Other people’s feelings may be an afterthought; may seem insensitive.

J-Judging — Orderly, organized, predictable. Feel best when work is done, things are as they should be.

P-Perceiving — Flexible, open-ended, somewhat spontaneous. Fairly independent, make decisions based on mood, timing, what feels right to them.

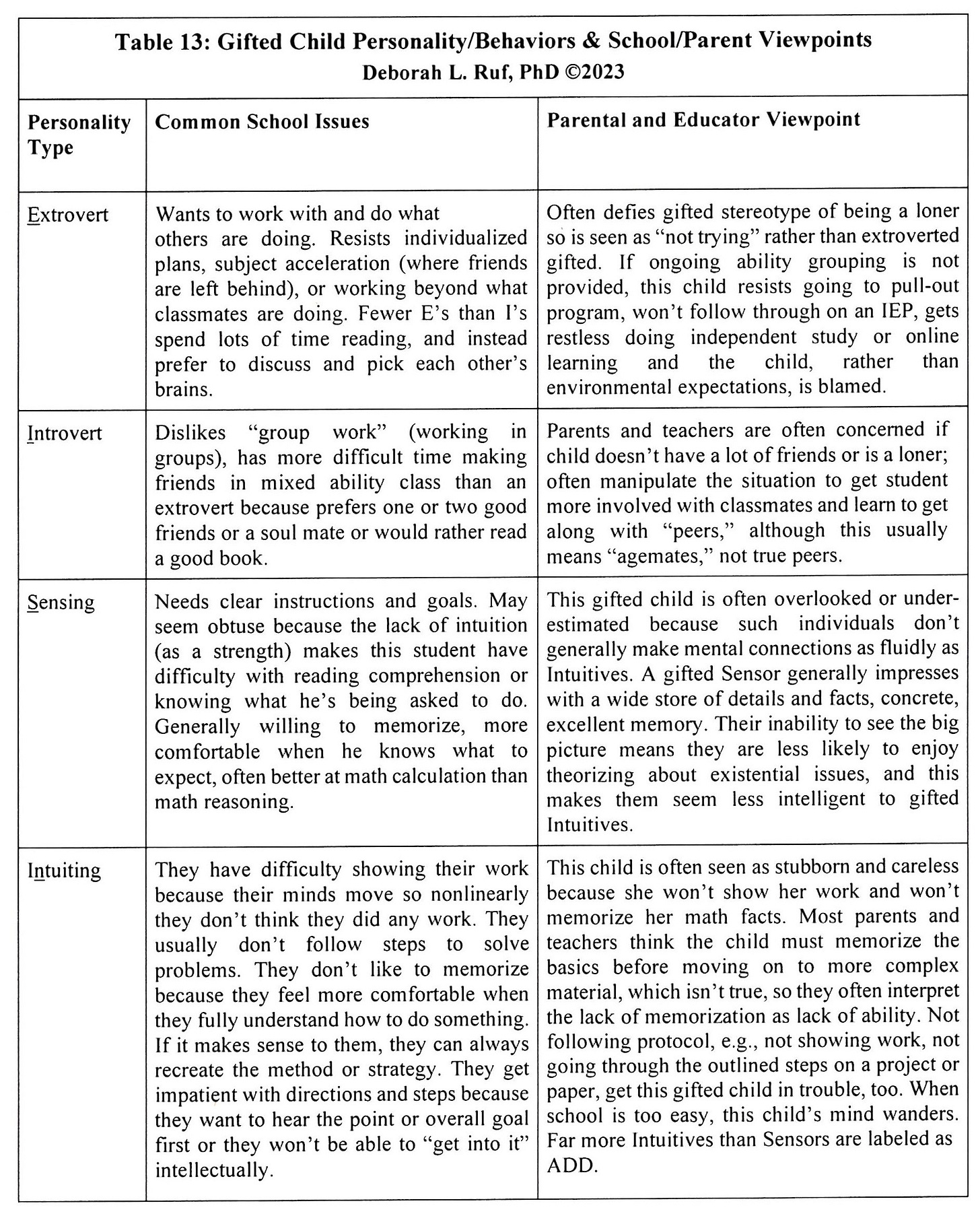

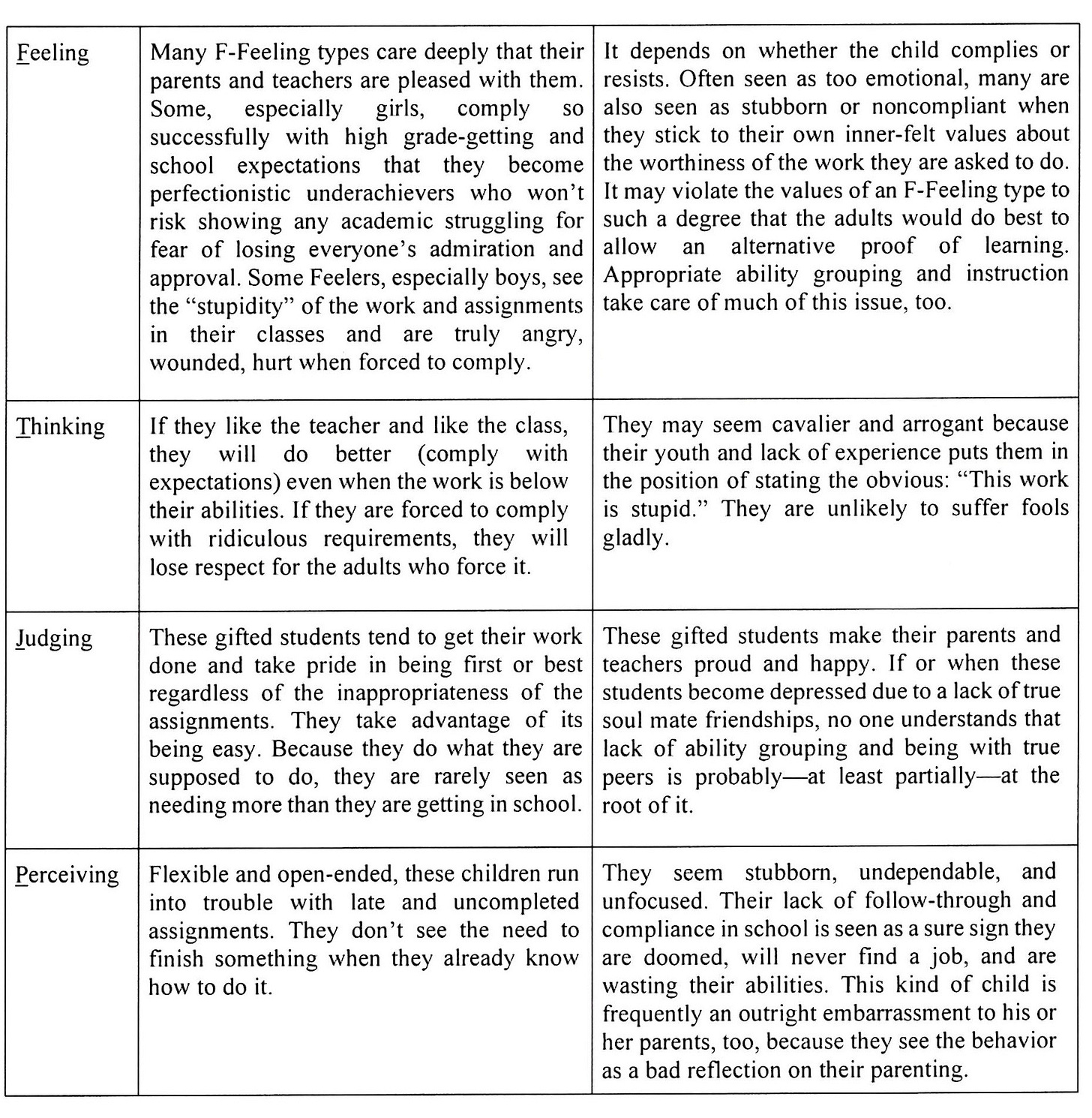

Here is a Table form I created and tweaked a dozen or so years ago. It is now Table 13 in the The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us (Ruf, 2023), book.

The preceding information shows some ways the different preferences contribute to somewhat predictable attitudes and behaviors of gifted students — and the reactions of adults in their lives. All of this is especially true for those who are in same-aged, mixed ability classrooms where their academic and intellectual peer relationship needs are not being met.

On top of all this, parent personality type has a great deal to do with gifted child adjustment regardless of the child’s type preference. For example, a laid-back, idealistic INFP child who has a similarly typed parent is much less likely to end up feeling like a failure than the child whose parent is an SJ type. Sensors are generally rule-and-procedure followers. They can’t easily relate to someone who chooses not to do something because it isn’t “right” for her. A Sensor parent is uncomfortable with a child who ignores what is normal and accepted behavior, and for such a parent, school performance is the first measure of self-worth.

FP children seem to wear their hearts on their sleeves, and a parent whose type ends in TJ might see the FP child as weak, stubborn, or irrational. If you tell the parents of an uncooperative, unhappy, under-performing, disorganized gifted child that their child has “executive function” disorder, as an example, they find it much easier to deal with a labeled learning disability than with a child who simply doesn’t do what she is “supposed” to do. It is almost always the school setting that brings out the worst in gifted children and changing the setting can clear up the “bad” behaviors.

Why, then, do many gifted specialists see so many more P-Perceivers and especially FPs? These are the most likely gifted children to find regular school — classrooms that group students by age rather than readiness to learn or intellectual ability — boring, painful, and a waste of time. I ask parents if they’ve ever used this statement with their child: “In the amount of time you’ve argued with me about this, you could have finished it.” Such a child is almost always a Feeler-Perceiver. A Thinker-Judger is more likely to do a less-than-perfect job but at least get it done. FPs, though, need their parents and teachers to understand them, so they need to have the argument. Thinkers simply dismiss — and lose respect for — the adults who made the foolish requirements and don’t care as much as Feelers do if the adults know why or understand them.

Parents have only so many options available to them when most schools group children by age — not ability — in mixed ability classrooms. When parents know how classrooms are set up and how their own children are likely to react to those circumstances and requirements, they can effectively intervene and give the correct support to their children. If parents know ahead of time how their own children will react to different options and adjustments, an IEP (Individual Education Plan), subject level acceleration, or online learning, for example, then they can select options that might work with their child.

When we know parent and child personality types, the benefits go in both directions. For the benefit of the child, it is possible to help the less flexible parent types to understand their child better and to help them change the child’s environment instead of trying to get the child to conform and comply with an inappropriate school situation.

Any parent who suffered during the school years wants to see his or her children do better. For these parents, understanding how the schools are set up and how their personality type or preferences affected their own experience can be a very real relief. And most importantly, when the use of personality typing helps parents and educators to understand better that the behavior of many gifted children in school is a response of their personality type within the specific educational environment, then more structural and programming changes to support these children may become available.

References

Betkouski, M., & Hoffman, L. (1981). A summary of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator research application in education. Research in Psychological Type, 3, 3–41.

Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Boston: Little, Brown.

Delbridge-Parker, L., & Robinson, D. C. (1989). Type and academically gifted adolescents. Journal of Psychological Type, 17, 66–72.

Gallagher, S. A. (1990). Personality patterns of the gifted. Understanding Our Gifted, 3(1), 1, 11–13.

Gross, M. (1993). Exceptionally Gifted Children. New York: Routledge Press.

Hoehn, L., & Bireley, M. K. (1988). Mental processing preferences of gifted children. Illinois Council for the Gifted Journal, 7, 28–31.

Hollingworth, L. (1942). Children above 180 IQ: Stanford-Binet: Origin and development. New York: World Book Company.

Jones, J.H., & Sherman, R.G. (1979). Clinical uses of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Research in Psychological Type, 2, 32–45.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development. New York: Harper & Row.

Lind, S. (2000, Fall). Overexciteability and the highly gifted child. California Association for the Gifted, 31, №4.

Lovecky, D. V. (1997). Identity development in gifted children: Moral sensitivity. Roeper Review, 20, 90–94.

Myers, I.B., & McCaulley, M.H. (1985). Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Myers, I.B., with Myers, P. (1980). Gifts differing. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Murphy, E. (1992). The developing child. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

O’Leary, K. (2005). Development of personal strengths and moral reasoning in gifted adolescents. Unpublished dissertation: University of New South Wales.

Piechowski, M. M. (2006). “Mellow out,” they say. If only I could: Intensities and sensitivities of the young and the bright. Madison, WI: Yunasa Books.

Piirto, J. (1998). The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and talented adolescents: Feeling boys and thinking girls: Talented adolescents and their teachers. Paper presented at the CAPT conference, Orlando, FL.

Piirto, J. (1998). Understanding those who create. Scottsdale, AZ: Gifted Psychology Press.

Renzulli, J. S. (2002). Expanding the conception of giftedness to include co-cognitive traits and to promote social capital. Phi Delta Kappan, 84, 33–58.

Ruf, D. (2023). The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us. Minneapolis, MN: 5LoG Press. See The 5 Levels of Gifted Children Grown Up: What They Tell Us (2023)

Sak, U. (2004). A synthesis of research on psychological types of gifted adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education.

Silverman, L. (1993). The gifted individual: The phenomenology of giftedness. In L. K. Silverman (Ed.), Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver: Love Publishing Company.

Terman, L. M. (1925). Mental and physical traits of a thousand gifted children. Genetic studies of genius (Vol. I). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Webb, J. T., Meckstroth, E. A., & Tolan, S. S. (1982, 1994). Guiding the gifted child: A practical resource for parents and teachers. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

More information can be found on

https://fivelevelsofgifted.com/